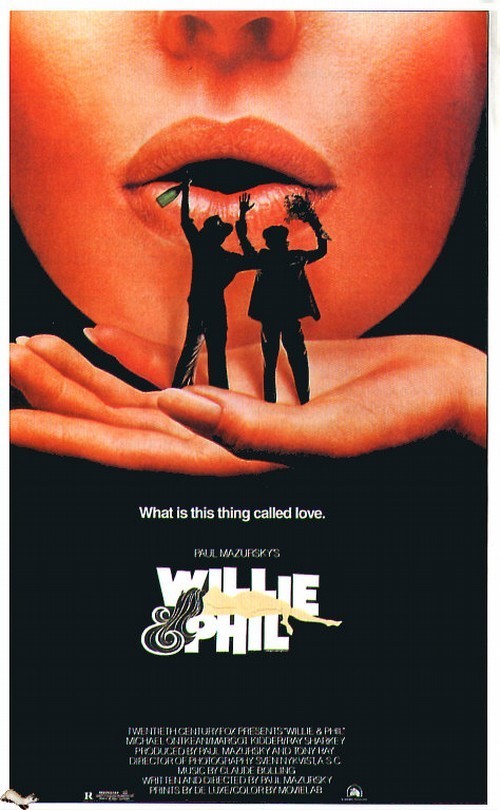

If Paul Mazursky’s “Willie and Phil” is supposed to be a psychologically plausible telling of this story, then it doesn’t work. The movie gives away its own game right at the beginning, with the reference to “Jules and Jim.” These aren’t real people in this movie; they’re characters. They don’t inhabit life, they inhabit Mazursky’s screenplay which takes them on a guided tour of the cults, fads, human potential movements, and alternative lifestyles of the decade during which zucchini replaced Faulkner as the most popular subject on campus.

But I don’t think was intended to work on a realistic level, or that we’re intended to believe that Willie, Phil, and Jeannette are making free choices throughout the movie. In a subtle, understated sort of way, Mazursky is giving us a movie that hovers between a satirical revue and a series of lifestyle vignettes. The characters in his movie are almost exhausted by the end of the decade (weren’t we all?). Not only have they experimented with various combinations of commitments to one another, but they’ve also tried out most of the popular 1970s belief systems.

Willie (Michael Ontkean) is a high school teacher as the movie opens, but he wants to be more, to feel deeply, to think on more exalted levels, and his journey through the decade takes him into radicalism, back to the earth, and all the way to India for lessons in meditation. Phil (Ray Sharkey) says he wants love and security, but he holds himself at arm’s length from Jeannette and other possible sources of love. Unable to communicate, he channels all of his energy into making it in the communications industries. Jeannette (Margot Kidder) … well, what does she want? To love, to be loved, to be possessed, to be free, to commit, but not to be trapped, to … have kids? A career? Willie? Phil?

I think Mazursky’s suggesting something interesting about the 1970s. It was a decade without a consuming passion, without an overall subject or tone. Every decade from the 1920s to the 1960s had an overriding theme, at least in our collective national imagination, but in the 1970s we went on life-style shopping trips, searching for an impossible combination of life choices that would be morally good, politically correct, personally entertaining, and outperform the market all at once.

And what were we left with in the 1980s? Confusion, vague apprehension, lack of faith in belief systems, EPA mileage estimates, megavitamins as the last blameless conspicuous consumption, and, echoing somewhere in the back of our minds, Peggy Lee singing “Is That All There Is?” How’d we get stuck? Why’d we wind up with a sense of impending doom when we tried every possible superficial substitute for profound change? Mazursky finds this note and strikes it in Willie and Phil, and that’s what’s best about his movie.

But like the decade itself, “Willie and Phil” is not completely substantial or satisfying. What redeems it, curiously, are the scenes involving Willie’s Jewish parents, Phil’s Italian parents, and Jeannette’s Southern mother. Their scenes are reactions to what’s happening to their kids in the 1970s, and they work like field trips from other decades. The parents observe, try to understand, are baffled, react with resentment, anger, love, confusion. I loved it when the Italian mother, trying to figure out how Jeannette was going to sleep with her boyfriend in the house of her ex-husband while the ex-husband bunked downstairs and the parents took the guest room, got up, said it was all just too complicated for her, and left for the airport. That’s sort of the motif for this movie.