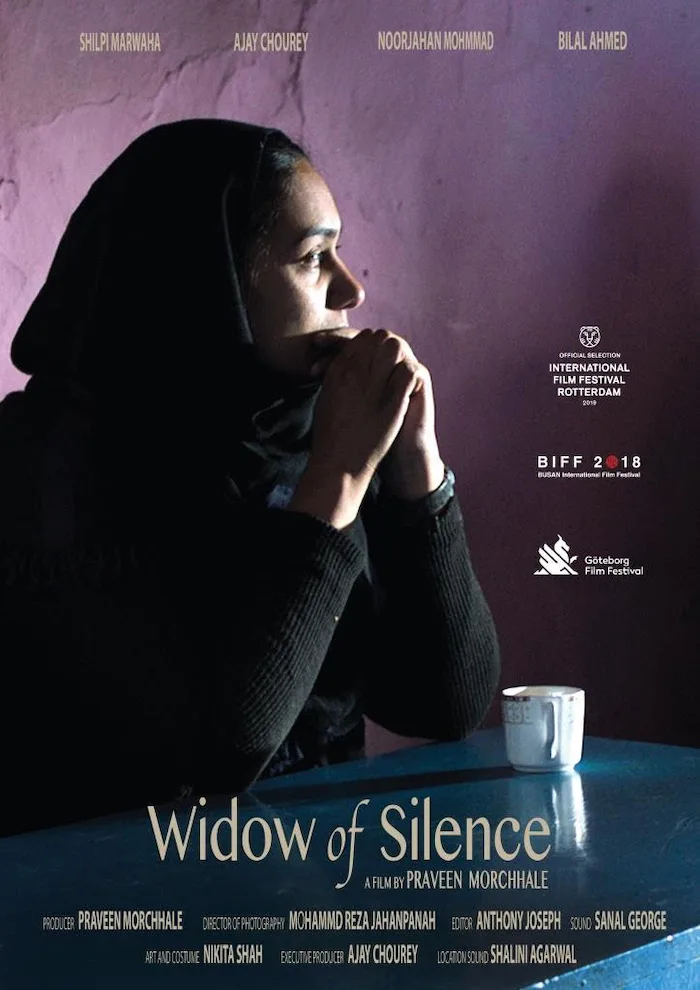

“I’m already in the coffin,” admits an elderly Islamic woman while riding in a taxi. She’s headed to the Kargil War Memorial where she plans to place flowers on the grave of her son, whose death has rendered her a living corpse. Like many of the women in Praveen Morchhale’s quietly enraging film, “Widow of Silence,” she is akin to a flower plucked against its will by unfeeling hands. An opening title card informs us that Morchhale’s script is “based on many true stories” told to the director by various female inhabitants of Kashmir—the volatile Indian region currently administered by three countries—who are branded as “half-widows.” They are the stigmatized souls whose husbands have vanished during the region’s three-decade-long conflict, yet have not been officially declared dead, thus putting their loved ones at the mercy of a viciously corrupt bureaucratic system designed to deny them their rights. One deliberate typo on all-powerful government papers can take ages to correct. As a registrar (Ajay Chourey) explains with matter-of-fact malevolence, “You won’t be able to prove before your death that you are alive.”

<span class="s1" <this="" is="" the="" misogynistic="" quagmire="" that="" our="" heroine="" aasia="" (shilpi="" marwaha)="" finds="" herself="" up="" against.="" we="" first="" see="" her="" tying="" a="" despondent="" old="" woman="" (zaba="" banoo)="" to="" chair="" for="" reasons="" only="" gradually="" understand.="" morchhale="" could’ve="" easily="" tackled="" this="" subject="" in="" form="" of="" talking="" head="" documentary,="" but="" such="" an="" approach="" would’ve="" conflicted="" with="" his="" spare,="" observant="" style.="" he="" clearly="" understands="" power="" visual="" storytelling,="" and="" how—as="" one="" character="" pointedly="" observes—“silence="" gives="" people="" chance="" think.”="" mere="" image="" banoo="" strapped="" as="" sunlight="" streams="" through="" rectangular="" windows="" home="" conveys="" sense="" entrapment="" felt="" by="" every="" woman,="" degree="" or="" another,="" film.="" soon="" learn="" ailing="" elder="" aasia’s="" mother-in-law,="" who="" became="" catatonic="" once="" son="" was="" abducted="" indian="" military="" seven="" years="" ago="" supposed="" interrogation="" never="" returned.="" particulars="" alleged="" crimes="" committed="" husband="" are="" not="" interest="" morchhale,="" whose="" concern="" remains="" fixed="" on="" how="" man’s="" absence="" has="" robbed="" women="" were="" close="" him="" their="" own="" lives="" long="" before="" they="" have="" taken="" final="" breaths.

This is the misogynistic quagmire that our heroine Aasia (Shilpi Marwaha) finds herself up against. We first see her tying a despondent old woman (Zaba Banoo) to a chair for reasons we only gradually understand. Morchhale could’ve easily tackled this subject in the form of a talking head documentary, but such an approach would’ve conflicted with his spare, observant style. He clearly understands the power of visual storytelling, and how—as one character pointedly observes—“silence gives people the chance to think.” The mere image of Banoo strapped to a chair as sunlight streams through the rectangular windows of her home conveys the sense of entrapment felt by every woman, to one degree or another, in the film. We soon learn that the ailing elder is Aasia’s mother-in-law, who became catatonic once her son was abducted by the Indian military seven years ago for a supposed interrogation and never returned. The particulars of the alleged crimes committed by Aasia’s husband are not of interest to Morchhale, whose concern remains fixed on how the man’s absence has robbed the women who were close to him of their own lives long before they have taken their final breaths.

Marwaha movingly embodies the pervasive weariness that reverberates throughout each scene, as characters are forced to endure the same cyclical conversations that guarantee no closure. Cinematographer Mohammad Reza Jahanpanah juxtaposes Aasia’s misery against gorgeous landscapes that almost appear to taunt her with their suggestion of tranquility. Time and again, she travels along the same appropriately zigzagging road, rushing back and forth from wholly unproductive meetings with the aforementioned registrar, who repeatedly denies her request for her husband’s death certificate, which would provide her with the ownership of her own home, thus securing her family’s economic future. My heart broke for Aasia’s 11-year-old daughter, Inaya (Noorjahan Mohammad Younus), who is bullied constantly at school by insecure peers about her father, whom neither her mother nor her grandmother are willing to discuss. The only time we see his face is when Inaya tears his photograph to pieces before putting them back in place, an apt metaphor for the fragments these families are forced to reassemble, which rarely add up to a satisfying whole.

<span class="s1" There are times when the dialogue becomes overstuffed with exposition, such as when certain factual details are spelled out for the obvious benefit of the audience, since the characters have already gotten the memo. It’s unclear whether some of the lines were marred by the stilted subtitled translations, which are laden with enough errors to necessitate further editing. Yet it is a testament to Morchhale’s writing that its eloquence frequently manages to shine through regardless, especially in the sequences involving the taxi driver (played wonderfully by Bilal Ahmad, an actual taxi driver from the region) who quickly emerges as the film’s life force. As his car radio reports on the area’s latest terrorist attacks, the driver partakes in sardonic and poetic banter with everyone he encounters, whether they be passengers or border patrol. He provides the movie with its only glimmers of levity, such as when he pokes fun at the absurdity of Islamic law forbidding women from sitting next to men. His words are refreshing because they relate to the central action more like a Greek chorus would, artfully expressing the picture’s underlying themes in ways that may not be immediately apparent.

Ahmad’s repeated likening of Kashmir to heaven calls to mind the deceptively hopeful title of Douglas Sirk’s melodrama, “All That Heaven Allows,” which goes on to illustrate just how little heaven considers allowable. It’s not long before Aasia is pinned to a chair just as her mother-in-law was, as the registrar lays out precisely what she’ll be expected to do in order to rightfully obtain her ancestral one-third acreage of land. What he’s requesting isn’t a bribe, he assures her, but rather a support system of sexual favors that the government considers par for the course. “Seven years can make land barren without farming,” he argues, another instance in the film where women are objectified as either fertile soil or flowers in bloom. Rather than raise her voice, Aasia often pivots away from the registrar’s unwanted advances as if they were the spray of gunshots she hears outside her home at night, prompting her to blow out the candles. Any further context to these unseen terrors would’ve been superfluous. The audience is kept in the dark along with Aasia to the point where we begin feeling her mounting, viscerally unsettling frustration.

For the entire film, Aasia straddles the line between the past and the present, heaven and hell, the living and the dead. I’ll refrain from revealing anything else about her journey, apart from that it leads to a brilliant punchline. All we hear during a crucial moment is a trickling of liquid as inconspicuous as the water Aasia uses to feed her plants in the first scene, bringing the movie full circle with a payoff that is wholly unexpected. The final four minutes turn what was already a fine picture into an unforgettable one, affirming Morchhale’s status as one of the most exciting figures of the Indian new wave.

Now playing in virtual cinemas.