At not quite the halfway point of “Whitney,” a well-done but all-too-woeful wallow of a documentary that recounts Whitney Houston’s swift rise to unparalleled stardom and tragic decline that ended in 2012 after she drowned in a hotel bathtub at age 48, there arrives a segment devoted to perhaps her brightest moment as an entertainer. That would be her uniquely stirring rendition of “The Star-Spangled Banner” at Super Bowl XXV in 1991, shortly after the start of the Gulf War.

Director Kevin Macdonald (“The Last King of Scotland,” “Touching the Void”) recruits the song’s producer, Rickey Minor—one-time bandleader for “The Tonight Show with Jay Leno”—to explain how he changed the song’s usual waltz tempo from 3/4 time to 4/4. That provided the then-27-year-old star enough room to breathe and pour her soul into her glorious performance. Yes, what you hear was pre-recorded but there is still a spark of spontaneity to it, given that it was Houston’s one and only take.

I was surprised how moved I was, even years later, after hearing her treatment of the national anthem again. Word to the wise: Appreciate that goose-pimply triumph when it arrives, because matters quickly begin to grow ever darker from there on. Unlike “Amy”—the 2015 Oscar-winning doc about Amy Winehouse, another bedeviled singer gone too soon—there are no personal lyrics to pay homage to her talent and capture her state of mind. Here, Houston’s music takes a back seat to digging for the reason why she never really felt comfortable in her own skin.

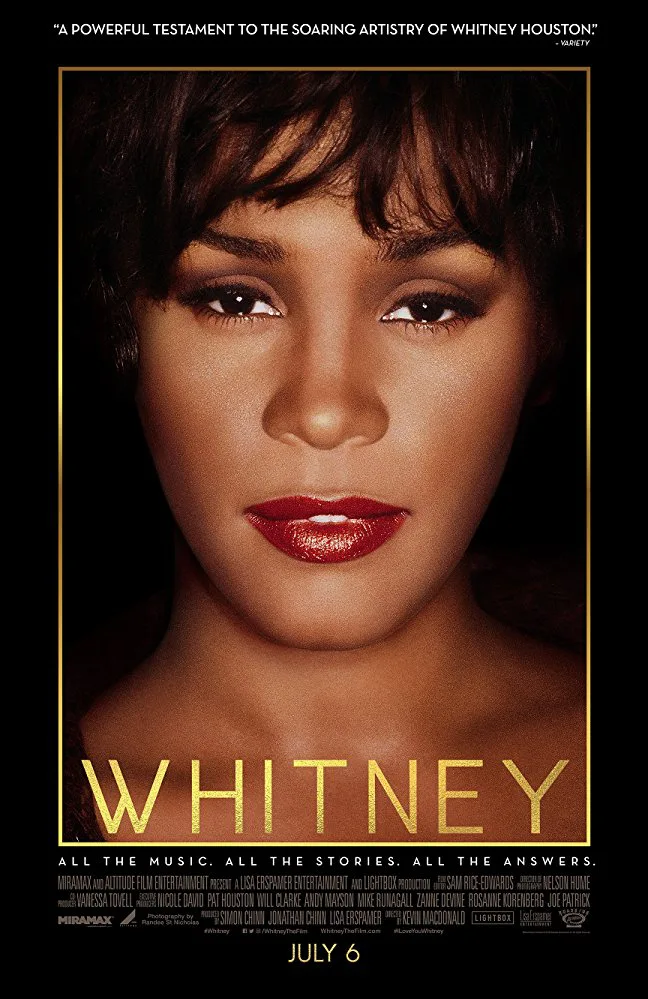

This is the second recent plunge into Houston’s life after last year’s “Whitney: Can I Be Me.” That more sensational effort made hay from the singer’s romantic relationship with Robyn Crawford, her supportive lesbian lover who was part of her life from age 18. Macdonald’s super-sized approach to the usual rise-and-fall tale earned the support of Houston’s estate, making it packed with insights from friends, associates, hired hands and family as well as never-seen footage. While their anecdotes initially are congenial and caring, it becomes horrifyingly apparent just how complicit her own loved ones were in indulging and capitalizing upon her more destructive tendencies while warping her sense of self.

We first hear Houston’s voice in between jarring flashes of her MTV video featuring her early hit, “I Wanna Dance with Somebody,” as she describes a recurring dream, “I am always running from the giant.” She was born to Cissy Houston, an in-demand backup singer for everyone from Aretha Franklin and Elvis who struggled to be a solo act, and theatrical manager John Russell Houston Jr., who bestowed the nickname of “Nippy” on his daughter when she was a fussy baby. Whitney grew up in Newark, N.J., and was often bullied over the lightness of her skin, which partially explains her persistent images of that giant in pursuit. When Houston got famous, she was bullied by those critics thought she was too pop and not enough R&B, even getting booed in 1988 when she won a Soul Train Award for her second album, “Whitney.”

Tabloids over the years placed much blame on her Norman Maine-ish husband of 15 years, singer Bobby Brown, whose flash of a career was on the verge of fading when the pair wed in 1992. (He briefly speaks on camera, refusing to discuss the effect that drugs had on her and how they led to her death.) But it turns out, her brother Michael and half-brother Gary Garland, a disgraced NBA player, admit that they, not Brown, first introduced their little teen sister to drugs long before he came along. As for Cissy, she was a dictatorial stage mother, guiding her angelic church choir standout of a daughter’s ascent into the spotlight, first as a teen backup singer, then as a fashion model and eventually as a recording artist. It turns out many relatives were riding the Whitney gravy train, getting paid just for hanging around backstage while the star did all the work. This globe-spanning sensation would end up losing most of the money she earned from her never-topped record of seven consecutive No. 1 singles on the Billboard Hot 100 chart as well as the soundtrack album for her 1992 movie debut, “The Bodyguard,” whose version of Dolly Parton’s “I Will Always Love You” remains the best-selling single by a female artist in music history.

But according to her aunt, Mary Jones—who found a dead Houston face down in the bathtub—one of the contributing factors to the singer’s inability to mesh her sweetheart public image as Whitney and her more “ghetto” wild side as Nippy was a long-held secret. When her mother was on the road and her father was busy, she and her brother Michael were looked after by others. Unfortunately, one of their caretakers was their cousin, Dee Dee Warwick, Dionne Warwick’s sister, who would sexually abuse the siblings. Not helping were the infidelities, especially her mother’s affair with their church minister, which led her parents to divorce

Houston’s greatest failure might have been the damage she and Brown did to their only child, Bobbi Kristina, with their physically abusive fights, their hard-partying lifestyle, their ugly public peccadilloes and a lack of parenting skills. It’s overwhelmingly sad that their 22-year-old daughter would be gone three years after her mom passed away. She, too, was found face down in a bathtub before dying months later after being put into an induced coma.

The dirt is definitely covered in Macdonald’s film. There are villains in every corner. And Houston spent most of her final years looking and acting like one of the walking dead, despite stints in rehab. She was a wraith-like image of once-luminous self during in a 2002 TV interview with Diane Sawyer when she croakily admitted to using drugs before declaring that “crack was whack.” I wish Macdonald had included footage from Bravo’s 2005 train wreck of a reality show “Being Bobby Brown,” when Houston famously declared, “Hell to the no.” She did pull herself together for one last hurrah to play the church-going matriarch of a sisterly singing trio in the 2012 remake of the showbiz saga “Sparkle,” one of her favorite movies from her youth. But once the filming stopped, she brought the curtain down on herself.