Carrol Jo Hummer gets out of the service with his eyes practically shining at the glory of his dream: He’ll buy his own semitrailer and become that pillar of free enterprise, the independent owner-operator. He’s a lad Horatio Alger would have been proud of-forthright, plucky and hard-working. What he doesn’t understand, alas, is that he’s landing himself in a morass of corruption. Before the movie’s over, he will be driven to suicide: not his own, but his truck’s.

He’s the hero of “White Line Fever,” a movie demonstrating that, while I know little about trucking, the film’s maker arguably know less. They ask us to believe, for example, that it’s the plight of independent owner-operators to constantly be forced (sometimes at the risk of their lives) to carry loads of contraband items. The fact is that most owner-operators carry pretty much what they damn well please. The movie might have been a little closer to the facts if it had taken on the teamsters-but why look for trouble?

Trouble, in any event, certainly comes looking for poor Carrol Jo. All he wants is to be Mr. Middle America. He has a wife and a house and his business and he’s a straight shooter. But before the movie’s over he’ll be a cross between Buford Pusser and Billy Jack.

His antagonists are the owners of the Glass House trucking conglomerate, a corporate titan that inhabits a gigantic (did you beat me to it?) glass house out in the middle of the desert. This structure is so tall, so impossibly vast, that it looks less like architecture than like a trial run for one of the monoliths in “2001.” And it’s altogether alone. There aren’t even any parking lots around it for, uh, trucks or anything.

The lords of the Glass House are properly aloof, but they direct the activities of goons and thugs who, at one time or another (a) set Carrol Jo’s house aflame, (b) beat him up, (c) sabotage his truck, (d) put a rattlesnake in his cab, (e) beat his wife so severely she has a miscarriage and (f) put him in the hospital. This is one put-upon guy.

Along the way, however, he picks up a following among other independent owner-operators, who are, to a man, tired of livin’ and scared of dyin’, and they look upon him as their leader. He tries to deal with the Glass House gang, they try to buy him off, and then there’s the attack on his house and he lands in the hospital. And then we get the movie’s embarrassingly maudlin final scene, a rip-off from “Billy Jack,” in which Carrol Jo comes out of the hospital in his wheelchair and there’s a sea of hundreds of his followers, all smiling bravely, eyes wide with admiration for his courage, and he musters up a plucky grin which inevitably becomes the final freeze frame.

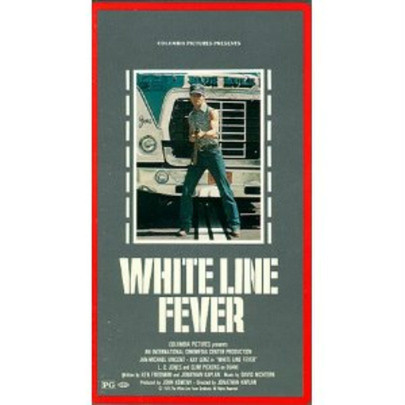

What saves the movie, to the degree that it’s salvageable, is the performance of Jan-Michael Vincent as the truck driver. He’s a young actor with an uncommonly convincing presence.

Because we tend to like him and identify with him, we put up with the implausibilities in “White Line Fever.” His dilemmas seem deeply felt enough that we forgive the plot. Still, if trucking were really as hazardous as it seems here, there’d be a lot of lettuce in Arizona that never made it into chef’s salads in New York.