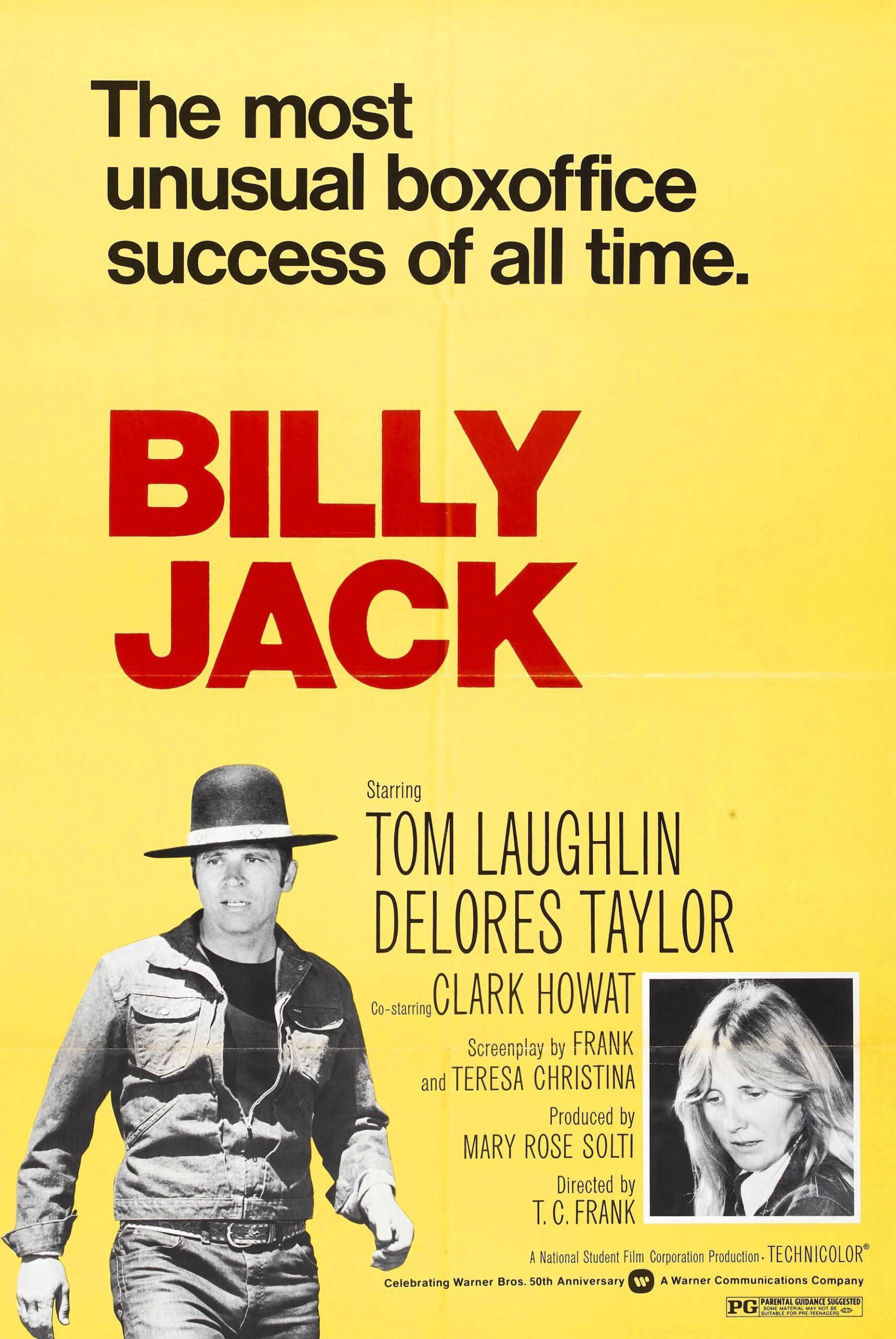

What I find interesting is that they decided, in effect, to remake their earlier film: not to copy it, but to grapple again with the same identities and ideas. Both films are about a character named Billy Jack (Tom Laughlin), who is a returned Vietnam hero, half-Indian, a master of karate, who takes the law into his own hands because he believes that’s the only way to obtain justice.

In “Born Losers” an outlaw motorcycle gang terrorizes a community and its sheriff’s office. When they brutally beat a teenager, Billy Jack steps in and shoots one of them. He gets ninety days. The gang members get a slap on the wrist for assault. But when he gets out of jail he finds the police powerless and the community terrified. So, because he feels he must, he fights them again, using karate, gasoline, Indian tricks, and his rifle.

In “Billy Jack,” the same character has become more mythic and supernatural. “We don’t know how to contact Billy Jack,” one of his friends says. “We communicate with him Indian-style; when we need him, somehow he’s there.” And indeed he is, riding his horse or motorcycle out of the woods, an almost supernatural presence. This time the town is terrorized, not by a bike gang, but by a brutal local businessman and his half-crazy sadomasochistic son. With the exception of the sheriff himself, who has good intentions but is ineffectual, the local law officers are on the side of evil against good.

“Good” is represented by a freedom school run by Delores Taylor, “where children can come when they have no place else to go.” The townspeople (who are conveniently represented as hateful, violent, and prejudiced) resent the “hippie school,” but it’s on an Indian reservation and thus accountable only to federal law.

The daughter of a deputy sheriff runs away after a beating and is hidden at the school, and this provides the food for the plot: The deputy and the other bad guys go after Billy Jack, who single-handedly cuts them down with karate blows, etc. The kids and staff at the school are all pacifists, but Billy Jack can’t buy that. His morality is a simple Old Testament one, an eye for an eye.

There are a lot of things in “Billy Jack” that are seriously conceived and very well-handled. Some of the scenes at the school, for example, with real kids experimenting with psychodrama, are interesting. Some of the action scenes are first-rate. There’s a lot of dialogue, mostly involving putdown of the older generation.

But the movie has as many causes in it as a year’s run of the New Republic. There’s not a single contemporary issue, from ecology to gun control, that’s not covered, and toward the movie’s end you’re wondering how these characters — who are just ordinary folks in a small Southwestern town — managed to confront every single ethical hurdle in a few weeks of living. It’s possible, I guess, but it would keep you awfully busy, and then there are always the Jews in the Soviet Union to think about, and the Pakistan refugees.

I’m also somewhat disturbed by the central theme of the movie. “Billy Jack” seems to be saying the same thing as “Born Losers,” that a gun is better than a constitution in the enforcement of justice. Is democracy totally obsolete, then? Is our only hope that the good fascists defeat the bad fascists? Laughlin and Taylor are still asking themselves these questions, and “Billy Jack” arrives at a conclusion that is only slightly more encouraging.