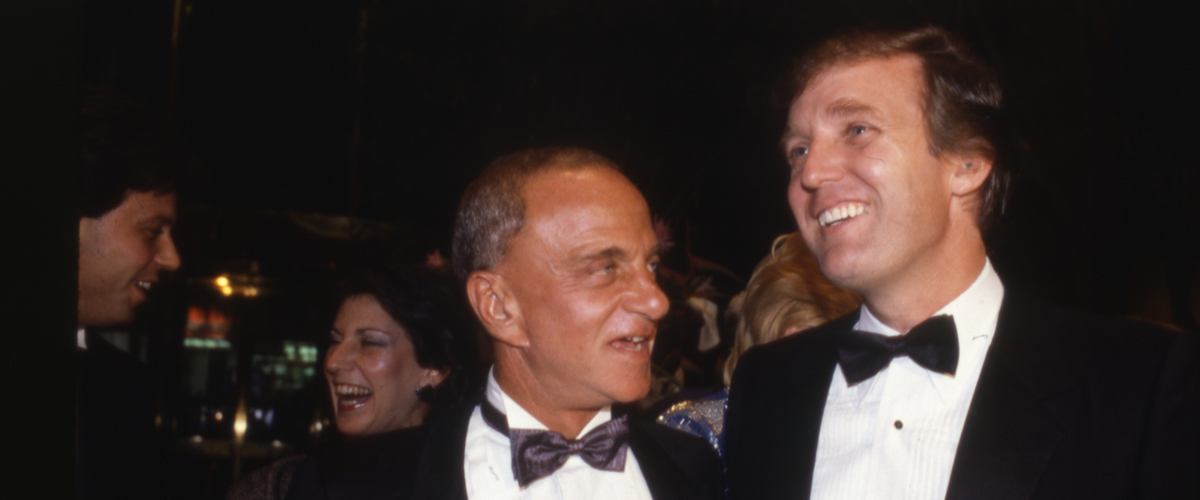

“Homosexuals have AIDS. I have liver cancer.” That corrosive line from Tony Kushner’s acclaimed play “Angels in America” is delivered by the character of Roy Cohn, a real person who was, in fact, gay, never had any kind of cancer, and would later die from AIDS-related causes. It sums up the life and personality of the real Cohn, one of the most notorious legal and political figures of the 20th century, and—according to many who knew him—a person who was in denial about a great many things, including his own capacity for delusion and the harm that he caused to friends, business partners, and the political institutions of the United States. Among his proteges is Donald Trump, a real estate heir and local celebrity in the 1970s and ’80s who would go on to become president, in large part by using the gutter tactics, including scapegoating and media manipulation, that he learned at Cohn’s knee.

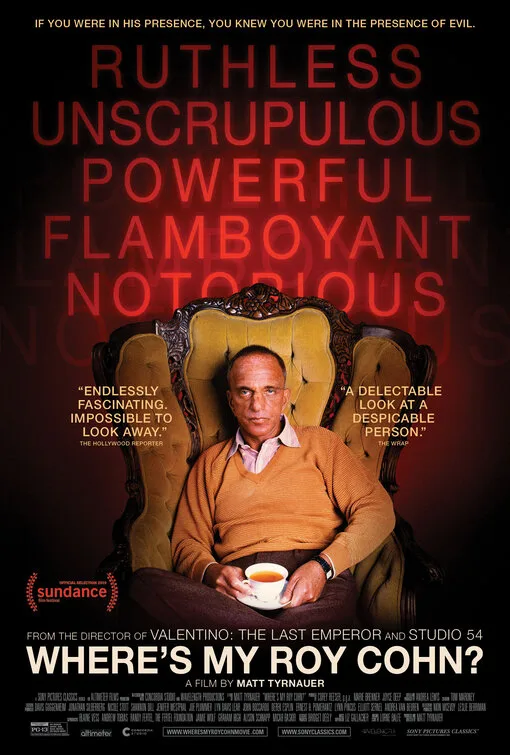

Cohn is the subject of “Where’s My Roy Cohn?”, a documentary by Matt Tyrnauer (“Scotty and the Secret History of Hollywood“). Artfully rearranging familiar details, and augmenting them with handsome graphics and well-chosen photos, newsreel footage, video, and newspaper clippings, the movie won’t deliver any bombshell revelations to viewers who already know the outline of Cohn’s life from written biographies and TV documentaries and newsmagazines, and talk shows (some of which, including a Tom Snyder appearance and a Morley Safer profile, are quoted here). But it’s still worth seeing for the incisive witnesses the filmmaker has gathered to recount Cohn’s life and speculate on what made him tick.

Some knew him well, including feminist author Katie Roiphe and Pulitzer prizewinning education writer David L. Marcus, both Cohn’s cousins; attorney John A. Vassalo, who worked with him; and another famous Cohn protege, Republican political operative Roger Stone, who for some reason does his interviews while wearing a weird grey toupee that suggests a rugby helmet made of thin fleece. Other witnesses, including media reporter Ken Auletta and gossip columnist Liz Smith (who died in 2017, not long after sitting for her interview) dealt with Cohn as members of the press. None have flattering thing to say about Cohn—not even Stone, who mainly seems awed of his mentor’s shamelessness.

A prodigy who graduated Columbia law school at 20, a year before he was eligible to pass the bar exam, Cohn quickly became a counsel to Sen. Joseph McCarthy. McCarthy’s postwar anti-communist initiatives were questionable persecutions on their face and often lacked evidence anyway, yet they had their intended effect of consolidating McCarthy’s power in Cold War America and striking fear into the hearts of his enemies. His various investigations ruined reputations and drove his targets to unemployment, exile, and suicide. Cohn relished being one of their key architects. The Army-McCarthy hearings, spearheaded mainly at Cohn’s behest, were the senator’s undoing, and they came about primarily because Cohn was in love with another of McCarthy’s counsels, G. David Schine. Schine was the heir to a New York hotel chain and chief consultant to the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations; when he entered the U.S. Army, Cohn tried to get preferential treatment for him, and tried to bring the Army itself in for a televised anticommunist fishing expedition as retribution for not doing what he wanted.

Much is made of how Cohn’s obsession with Schine was part of his lifelong attraction to buff, square-jawed, Aryan-looking men who stayed young even as Cohn aged. His taste in partners, say witnesses, belied his publicly straight face (nobody could be out during that period of US history anyway) and confirmed his cultural self-loathing (more than one witness describes Cohn as a man who hated his Jewishness and wished to escape it). Stone would later insist to The New Yorker, “Roy was not gay. He just liked having sex with men.” It’s in discussions of Cohn’s refusal to identify as a gay man that the film manifests something like empathy, pointing out the unrelenting homophobia that kept men of Cohn’s generation in the closet. (At the Army-McCarthy hearings, politicians who resented McCarthy and Cohn struck back by directing homophobic remarks at Cohn on camera.)

But this impulse to humanize Cohn only goes so far, because Cohn wasn’t merely hard to like; he seemed to relish being publicly hated, and treated the loathing of others as emotional fuel. After Cohn’s hubris inadvertently helped neutralize McCarthy and drove Cohn from Washington, he returned to New York and embraced his heel status, celebrating himself as a ruthless individual who seemed proud of his reputation for manipulation and viciousness. The litany of outrages packed into this movie’s brief running time would seem unbelievable if they weren’t true: they included running the Lionel Train company into the ground, possibly killing a young man in a yacht fire that was meant to collect insurance money, and getting disbarred for lying on a bar application, stealing clients’ funds, and pressuring a client to change a will. Even Cohn’s own demonstrable suffering in the closet doesn’t mitigate such behavior: as McCarthy’s right hand, he was responsible for the persecution and firing of other gay men whose sexual orientation was weaponized against them, to tar them as security risks.

But in his mind, Cohn was still the hero of his own story. And we get the impression from this film that, right up to the bitter, agonized end, he was engaged in an internal battle to justify himself to himself, and to the world. Kushner’s play explained Cohn’s brand of self-loathing better than Cohn ever managed to. “Homosexuals are not men who sleep with other men,” the character of Cohn insists to his doctor, Henry. “Homosexuals are men who, in 15 years of trying, can’t get a pissant anti-discrimination bill through City Council. They are men who know nobody, and who nobody knows. Now, Henry, does that sound like me?”

Header photo by Sonia Moskowitz.