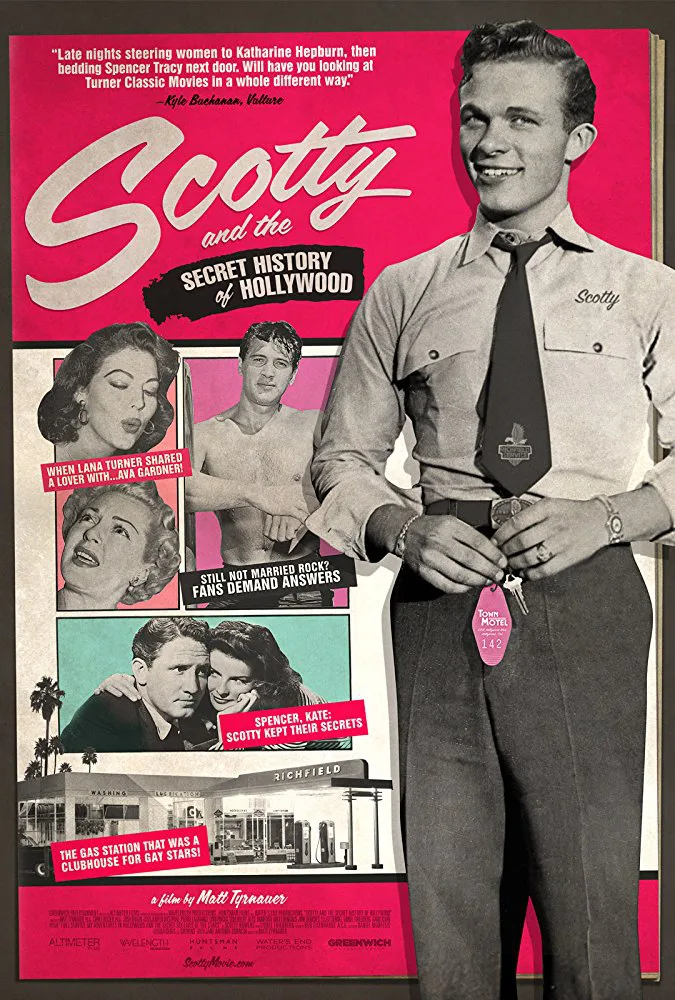

Matt Tyrnauer’s documentary “Scotty and the Secret History of Hollywood” has a more succinct and appropriate title than the 2012 nonfiction bestseller from which it derives, “Full Service: My Adventures in Hollywood and the Secret Sex Lives of the Stars,” written by Scotty Bowers with Lionel Friedberg. While the book seems to promise—and in fact, delivers—big dollops of sexual revelations about scores of classic-era movie stars, the film does a good job of placing all this Tinseltown rutting in the context of Hollywood’s industrial need to keep secrets and maintain squeaky-clean images for its most famous denizens.

Scotty Bowers, the protagonist of both book and film, was an Illinois lad who started enjoying sex even before puberty and did it for both pleasure and profit from the time he was a teen. After joining the Marines at age 18 at the outbreak of World War II, he was stationed in California before shipping out to the Pacific and would hitchhike to Los Angeles and hook up with men cruising the streets looking for action. In the war he saw some horrific battles, and then, in 1946, landed back in L.A., getting a job at a gas station on Hollywood Boulevard. One day, movie star Walter Pidgeon—or “Pidge” as Scotty calls him—motored in and invited the attractive young ex-Marine up to his house for an afternoon that included nude swimming and paid sex.

Thus was born a career that became one of Hollywood’s underground legends. Scotty not only “tricked” (his term) constantly himself, he also lined up a bevy of young friends, many of them ex-Marines, who would hang out at the gas station and wait for customers to meet them for dates that Scotty arranged. He even used the station, under the noses of oblivious bosses, for a steady stream of assignations and voyeuristic hijinks: a two-bed camper out back was used for quickie hookups while holes in the station’s bathroom wall allowed spectators to witness other action.

As sleazy as this may sound, Scotty presents it as robust, hedonistic fun in a more innocent time. Most of the young people (mostly men but also women) who got paid for sex earned $20 an outing and came away pleased, according to him: “It was $20 they wouldn’t otherwise have.” Scotty never applies the terms prostitute or hustler to himself, but conveys the impression that he loved sex so much he would have given it away if necessary. He also claims (and no one seems to have contradicted him) that he never accepted a dime for the thousands of dates he arranged, so he wasn’t a pimp in the usual sense.

Likewise, he eludes normal definitions of sexuality. While the great majority of his paying sexual relations seem to have been with men—as a Chicago teen, he says, he had sex with 25 to 30 Catholic priests—he claims to have preferred women (he had four long-term relationships with women, two of whom the film doesn’t mention). But heterosexual and bisexual aren’t labels he embraces any more than homosexual. Tyrnauer calls him “pansexual,” which seems fair enough. Also, perhaps, hypersexual: Scotty estimates he turned two or three tricks a day, seven days a week, for nearly 40 years. No wonder Dr. Alfred Kinsey discovered and used him in researching male and female sexuality (Scotty says he took the good doc to some Hollywood orgies and could tell he was turned on).

The clients Scotty and his fellow for-pay hedonists entertained ranged across the whole spectrum of American society, including business, the military and government (J. Edgar Hoover was one of his playmates, he says). In Hollywood, they included production designers, set decorators, hair stylists and other studio personnel. But, of course, the ones that attract the most ink and comment are the above-the-line names.

In this, Scotty mainly confirms or adds personal testimony to stories that have been rumored or reported elsewhere, but these still involve stripping a couple of layers of p.r. varnish from images that were once heavily lacquered. He discusses George Cukor’s home as an epicenter of Hollywood gay life from the ‘40s through the ‘60s, including its place in the lives of two of the director’s most illustrious actors, Spencer Tracy and Katherine Hepburn. With biographers backing him up, Scotty says that their supposed romance was a studio-created sham; in reality, both were gay. A similar fiction surrounded the relationship of Cary Grant and Randolph Scott, who were portrayed as “buddies” even as they lived together as lovers; Scotty says he had sex with both—separately, together and with other guys.

The film discusses other big-name clients of Scotty’s and the book delves into the predilections and preferences of many more. The overall effect is to suggest not only that Hollywood had a vested, longstanding interest in selling America a false, hypocritical image that stemmed from the nation’s Puritanical ideas about sex, but that homosexuality was the reality the powers-that-be were most anxious to suppress. Perhaps it still is. When people criticize Scotty today for “outing” celebrities who’ve been dead for decades, they’re not talking about revealing a star’s drinking habits or extramarital affairs. (Indeed, stories of Tracy’s adultery were used to cover his homosexuality.)

One of the film’s advantages over the book is that it brings in the testimonies of many other people—from friends and fellow ex-hustlers to Hollywood historians and insiders—all of whom support Scotty’s veracity while adding additional perspectives of their own. The film’s other advantage is that it allows us to spend time with Scotty himself. Now well into his 90s and the very picture of late-life physical vitality, he’s got such a ready smile and upbeat nature that you can easily believe he remained friends with many of his former clients, famous and not. He now lives with his wife Lois in a house in the Hollywood Hills (one of two willed him by a male lover) that he keeps in such a state of junk-clogged disarray that you can’t help but wonder about his mental make-up.

There are other things about both the book and the film to make you wonder. In neither is there a single mention of any sexually transmitted disease (prior to AIDS, which Scotty implies killed his and Hollywood’s sexual golden age) or any concern with preventing them. While detailing many sexual practices, Scotty is curiously coy about his own, never saying whether he was an active or passive partner in anal sex with his gay clients. In terms of Hollywood, he never refers to the widespread predatory behavior toward underage people (see the documentary “An Open Secret”), the age-old institution of the casting couch and exploitation of many young hopefuls in the entertainment business. In sum, it’s inevitably ironic that this film arrives in the era of #MeToo, for if Scotty has shined a valuable light into some of Hollywood’s dark corners, he’s left others languishing in guilty obscurity.