“Every kid knows who Freddy is. He’s like Santa Claus, or King Kong.” Line from “Wes Craven’s New Nightmare.” “Wes Craven’s New Nightmare” is a horror film within a horror film.

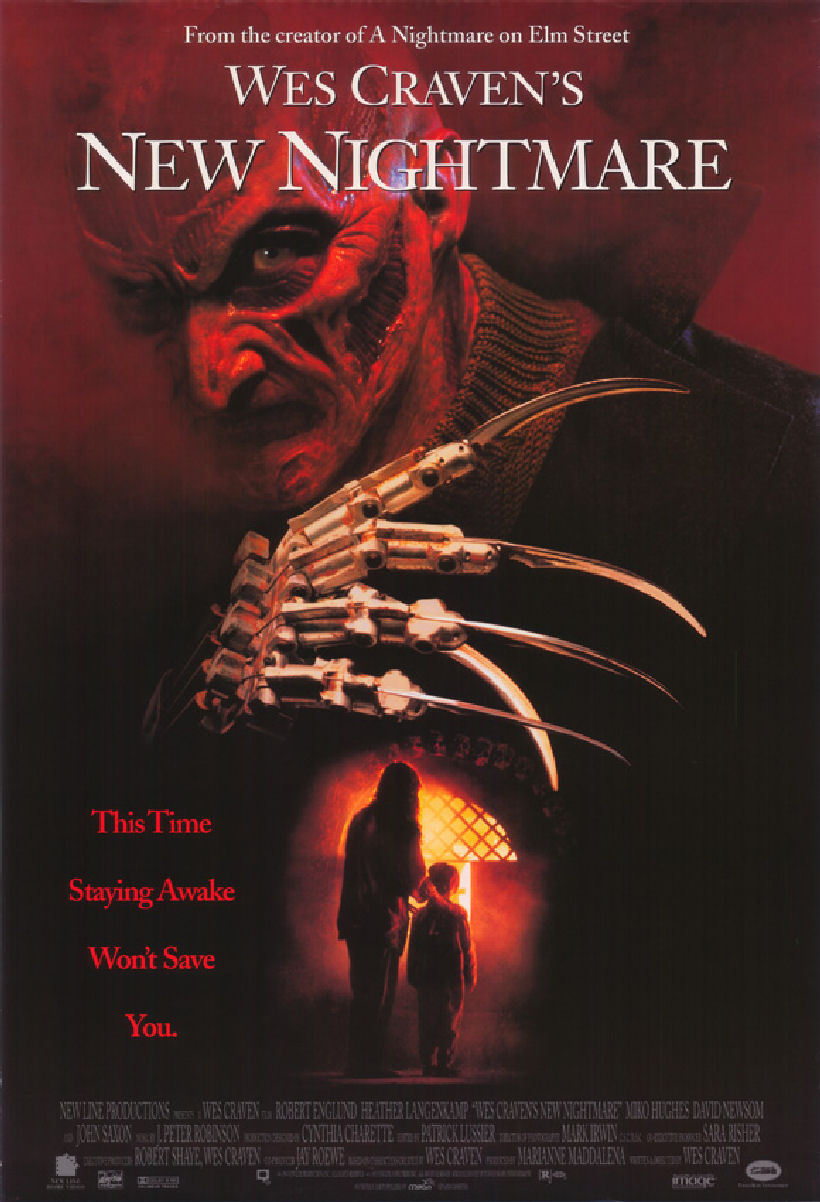

The director, who plays himself, explains at one point, “The only way to stop Freddy is to make another movie.” Freddy, of course, is Freddy Krueger, the most durable of modern horror monsters – a hideously scarred man in a felt fedora, who has knives for fingers.

He apparently died for once and all in “Freddy’s Dead: The Final Nightmare” (1991), the sixth film in the series, but that was exactly the problem: The “Nightmare” movies had generat ed an evil force which, once liberated by Freddy’s death, was set free to haunt the nightmares of the people involved in making the movies.

They would include Craven, who directed the original “Nightmare on Elm Street” in 1984 and now returns to the series for the first time; Heather Langenkamp, who was a teenager in the first movie and is now a young mother; Robert Englund, who plays Freddy; John Saxon, who appeared in the first and third films; and even Robert Shaye, founder and president of New Line Cinema, which has produced the series.

Considering that Craven’s original nightmare movie was famously inspired by a series of Los Angeles Times articles about people who told relatives of their fears of killer nightmares – and then died the next night – it would seem as if Craven and his cast are asking for trouble here. That’s part of the fascination, as “Wes Craven’s New Nightmare” dances back and forth across the line separating fantasy from reality. This is the first horror movie that is actually about the question, “Don’t you people ever think about the effect your movies have on the people who watch them?” As the movie opens, Langenkamp is happily married to a movie special effects guy (David Newsom), and dotes on their young son Dylan (Miko Hughes). Then a series of tragedies and alarming omens take place – including the real Los Angeles earthquake, which is seamlessly, inserted into the plot. She’s terrified. At the same time, other members of the “Nightmare” movies have had their sleep haunted by dreams suggesting, well, that the nightmare is not over.

Craven, a bearded, scholarly man who was once a humanities professor, is effective in the scenes where he discusses this phenomenon with Langenkamp and others: “We should never have killed Freddy,” he admits, because Freddy was not simply a fictional character played by the normal and friendly Robert Englund, but also a manifestation of ancient demonic forces which, enraged by his death, have returned.

Craven’s screenplay explores the possibilities of this situation in a way that loops back on itself, as New Line’s Shaye and other professionals play themselves. The answer obviously is to make another movie in order to exorcise the evil for once and all, but meanwhile there are psychiatrists, talk show hosts and others to consider, and questions that stray close to the creepy (“Would you trust Robert Englund alone with little Dylan?”) The climax of the film is one of those patented descents into the underworld that the “Nightmare” series has specialized in. The sets and special effects are by some of the same people who worked on “The Fugitive,” and there are truly amazing sequences, as when the little boy wanders across an eightlane freeway, or when the characters find themselves wandering in Freddy’s subterranean lair.

Serious fans of horror movies relate only in a secondary way to the chills themselves; they’re connoisseurs of the genre, the special effects, the makeup, the in-jokes. They’re going to love this movie, which seems to have been made not only for but by Fangoria fans. But it also works for general audiences. I haven’t been exactly a fan of the “Nightmare” series, but I found this movie, with its unsettling questions about the effect of horror on those who create it, strangely intriguing.