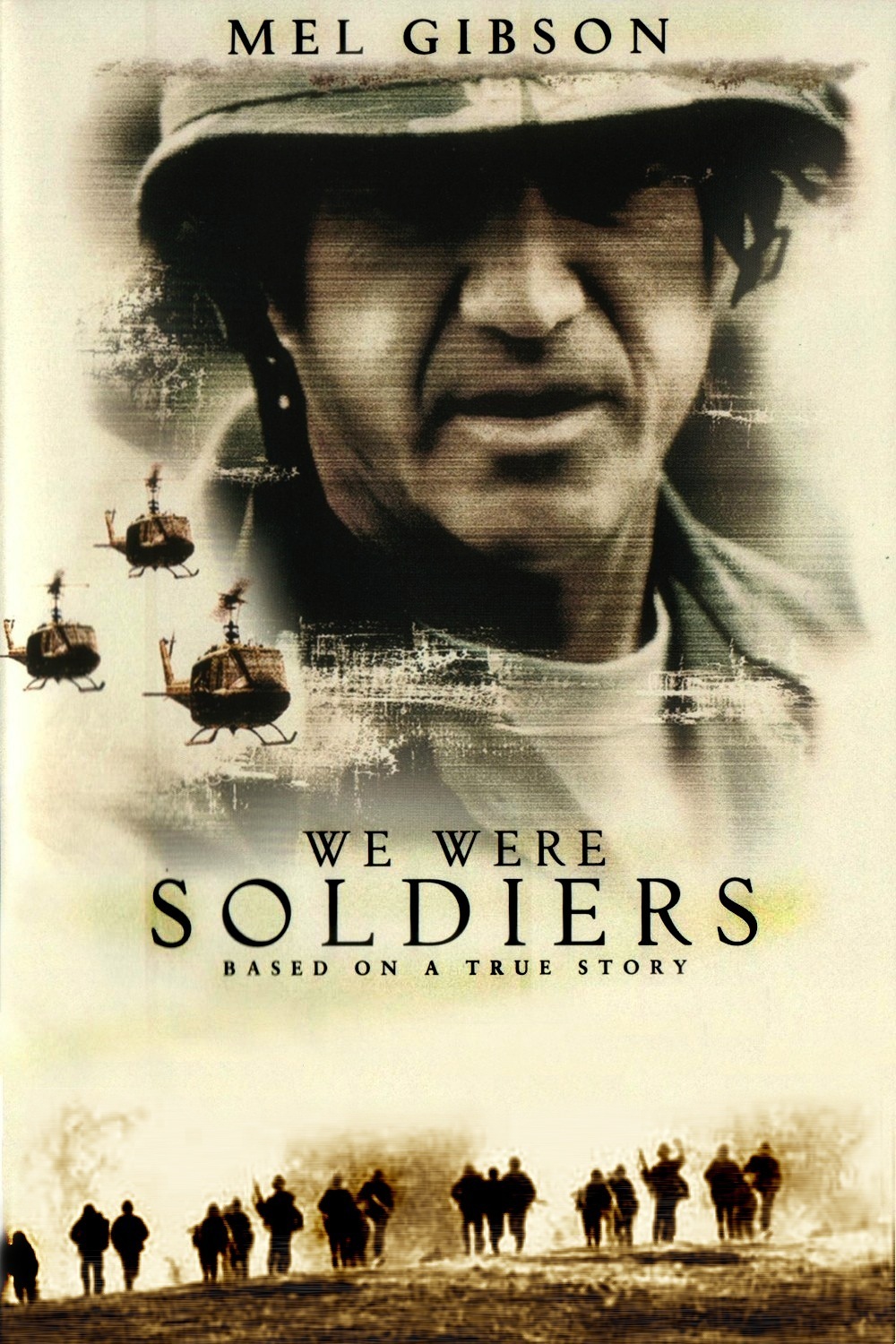

“I wonder what Custer was thinking,” Lt. Col. Hal Moore says, “when he realized he’d moved his men into slaughter.” Sgt. Maj. Plumley, his right-hand man, replies, “Sir, Custer was a p—-.” There you have the two emotional poles of “We Were Soldiers,” the story of the first major land battle in the Vietnam War, late in 1965. Moore (Mel Gibson) is a family man, and a Harvard graduate who studies international relations. Plumley (Sam Elliott) is an Army lifer, hard, brave, unsentimental. They are both about as good as battle leaders get. But by the end of that first battle, they realize they may be in the wrong war.

The reference to Custer is not coincidence. Moore leads the First Battalion of the Seventh Cavalry, Custer’s regiment. “We will ride into battle and this will be our horse,” Moore says, standing in front of a helicopter. Some 400 of his men ride into battle in the Ia Drang Valley, known as the “Valley of Death,” and are surrounded by some 2,000 North Vietnamese troops. Moore realizes it’s an ambush, and indeed in the film’s opening scenes he reads about just such a tactic used by the Vietnamese against the French a few years earlier.

“We Were Soldiers,” like “Black Hawk Down,” is a film in which the Americans do not automatically prevail in the style of traditional Hollywood war movies. Ia Drang cannot be called a defeat, since Moore’s men fought bravely and well, suffering heavy casualties but killing even more Viet Cong. But it is not a victory; it’s more the curtain-raiser of a war in which American troops were better trained and better equipped, but outnumbered, out maneuvered and finally outlasted.

For much of its length, the movie consists of battle scenes. They are not as lucid and easy to follow as the events in “Black Hawk Down,” but then the terrain is different, the canvas is larger, and there are no eyes in the sky to track troop movements. Director Randall Wallace (who wrote “Braveheart” and “Pearl Harbor“) does make the situation clear from moment to moment, as Moore and his North Vietnamese counterpart try to outsmart each other with theory and instinct.

Wallace cuts between the American troops, their wives back home on an Army base, and a tunnel bunker where Ahn (Don Duang), the Viet Cong commander, plans strategy on a map. Both men are smart and intuitive. The enemy knows the terrain and has the advantage of surprise, but is surprised itself at the way the Americans improvise and rise to the occasion.

“Black Hawk Down” was criticized because the characters seemed hard to tell apart. “We Were Soldiers” doesn’t have that problem; in the Hollywood tradition it identifies a few key players, casts them with stars, and follows their stories. In addition to the Gibson and Elliott characters, there are Maj. Crandall (Greg Kinnear), a helicopter pilot who flies into danger; the gung-ho Lt. Geoghegan (Chris Klein), and Joe Galloway (Barry Pepper), a photojournalist and soldier’s son, who hitches a ride into battle, and finds himself fighting at the side of the others to save his life.

The key relationship is between Moore and Plumley, and Gibson and Elliott depict it with quiet authority. They’re depicted as professional soldiers with experience from Korea. As they’re preparing to ride into battle, Moore tells Plumley, “Better get yourself that M-16.” The veteran replies: “By the time I need one, there’ll be plenty of them lying on the ground.” There are.

Events on the Army base center around the lives of the soldiers’ wives, including Julie Moore (Madeleine Stowe), who looks after their five children and is the de facto leader of the other spouses. We also meet Barbara Geoghegan (Keri Russell), who, because she is singled out, gives the audience a strong hint that the prognosis for her husband is not good.

Telegrams announcing deaths in battle are delivered by a Yellow Cab driver. Was the Army so insensitive that even on a base they couldn’t find an officer to deliver the news? That sets up a shameless scene later, when a Yellow Cab pulls up in front of a house and of course the wife inside assumes her husband is dead, only to find him in the cab. This scene is a reminder of “Pearl Harbor,” in which the Ben Affleck character is reported shot down over the English Channel and makes a surprise return to Hawaii without calling ahead. Call me a romantic, but when your loved one thinks you’re dead, give them a ring.

“We Were Soldiers” and “Black Hawk Down” both seem to replace patriotism with professionalism. This movie waves the flag more than the other (even the Viet Cong’s Ahn looks at the stars and stripes with enigmatic thoughtfulness), but the narration tells us, “In the end, they fought for each other.” This is an echo of the “Black Hawk Down” line, “It’s about the men next to you. That’s all it is.” Some will object, as they did with the earlier film, that the battle scenes consist of Americans with killing waves of faceless, non-white enemies. There is an attempt to give a face and a mind to the Viet Cong in the character of Ahn, but significantly, he is not listed in the major credits and I had to call the studio to find out his name and the name of the actor who played him. Yet almost all war movies identify with one side or the other, and it’s remarkable that “We Were Soldiers” includes a dedication not only to the Americans who fell at Ia Drang, but also to “the members of the People’s Army of North Vietnam who died in that place.” I was reminded of an experience 15 years ago at the Hawaii Film Festival, when a delegation of North Vietnamese directors arrived with a group of their films about the war. An audience member noticed that the enemy was not only faceless, but was not even named: At no point did the movies refer to Americans. “That is true,” said one of the directors. “We have been at war so long, first with the Chinese, then the French, then the Americans, that we just think in terms of the enemy.”