Across the world’s largest garbage dump, near Rio de Janeiro, the pickers crawl with their bags and buckets, seeking treasures that can be recycled: plastics and metals, mostly, but anything of value. From the air, they look like ants. You would assume they are the wretched of the earth, but those we meet in “Waste Land” seem surprisingly cheerful. They lead hard lives but understandable ones. They make $20 or $25 a day. They live nearby. They feel pride in their labor and talk of their service to the environment.

While the alleys of Chicago remain cluttered with ugly blue recycling bins that seem to be ignored and uncollected, the pickers rescue tons of recyclables from the dump and sell them to wholesalers, who sell them to manufacturers of car bumpers, cans, plastics and papers. They raise their children without resorting to drugs and prostitution. They have a pickers’ association, which runs a clinic and demonstrates for their rights. From books rescued from the dump, one picker has assembled a community library. The head of the association says he learned much from a soggy copy of Machiavelli, once he had dried it out. He quotes from it, and you see that he did.

I do not mean to make their lives seem easy or pleasant. It is miserable work, even after they grow accustomed to the smell. But it is useful work, and I have been thinking much about the happiness to be found by work that is honest and valuable. If you set the working conditions aside (which of course you cannot), I suggest the work of a garbage picker is more satisfying than that of a derivatives broker. How does it feel to get rich selling worthless paper to people you have lied to?

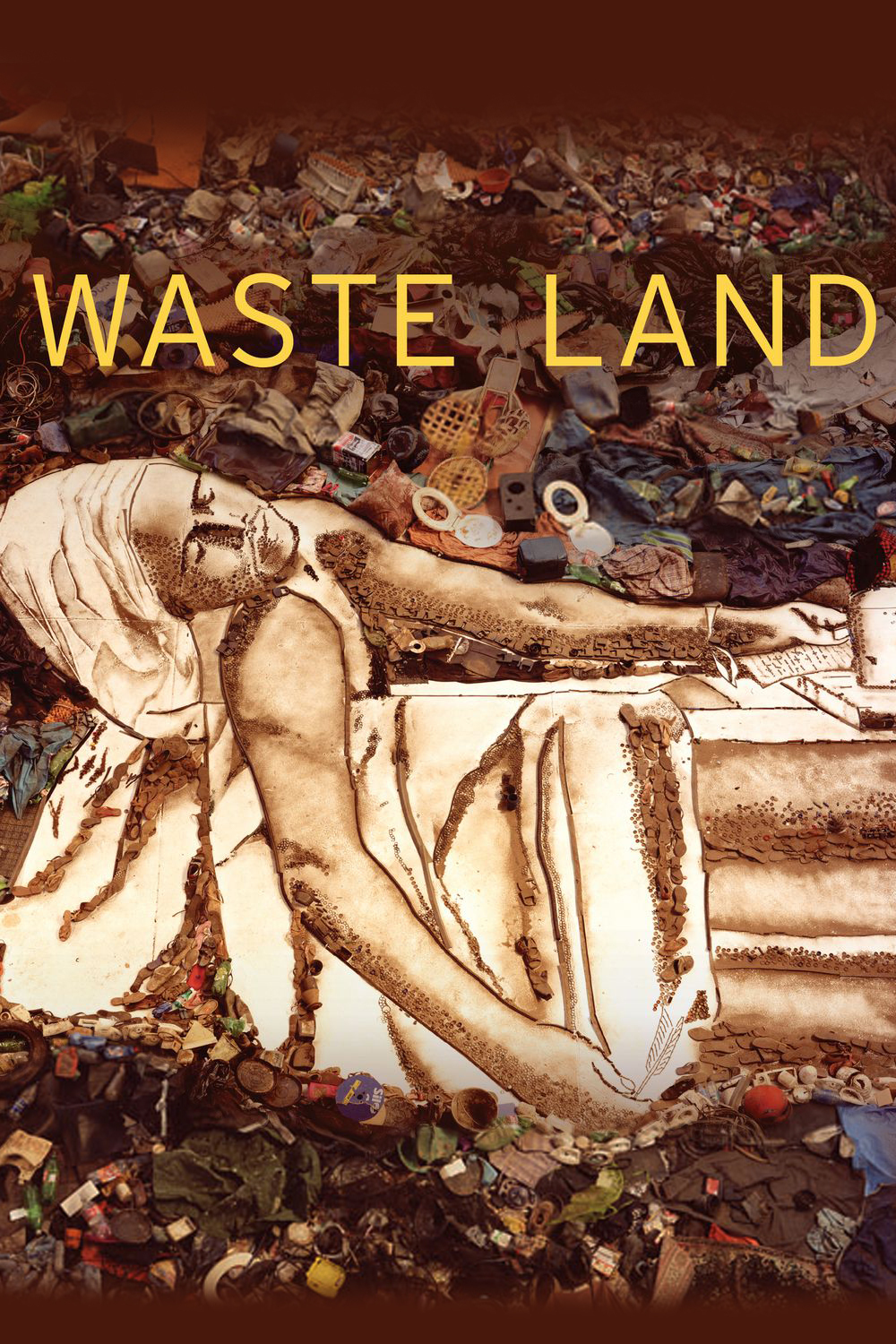

“Waste Land,” the documentary by Lucy Walker that has been nominated for an Academy Award this year, takes as its entry point into the lives of the pickers the work of the Brazilian artist Vik Muniz. As a youth, he had the good fortune to be shot in the leg by a rich kid, who paid him off; he used the money to buy a ticket to America, and now he is famous for art that turns garbage into giant constructions that he exhibits and photographs.

Perhaps Walker intended to make the film about Muniz. If so, her subject led her to a better one; as he returns to Rio to photograph pickers for a series of portraits, she begins to focus on their lives. We see where they live, we meet their families, we hear their stories, we learn of the society and economy they have constructed around Jardim Gramacho, the “Garbage Garden.” I was especially pleased by a woman named Irma*, who stirs a huge cauldron of beef stew in her outdoor kitchen constructed at the site.

The workers bring her unspoiled meat and usable vegetables, she says, and that is easy to believe if you have ever been to one of the all-meat restaurants facing the Copacabana beach, where the chefs wheel enormous pieces of beef, pork, lamb and poultry from table to table to carve slices and pile them on your plate. The waste here must be considerable.

Muniz has the advantage of speaking the same language as the pickers and having come from poverty. When he tells them his portraits will give them and their work recognition, they agree and are happy to cooperate, especially Tiao, who organized their association. Muniz intends to donate all the proceeds from his portraits to the pickers, which is simple enough, but then he and his wife, Janaina Tschape, have a discussion about whether he should invite Tiao to come along when his portrait is auctioned at Phillips.

Can you leave the life of a picker, fly to another country, stay in luxury and then return to a garbage heap? How do you handle that? It is a matter for endless debate, but eventually Tiao does join Muniz at the action, where his portrait follows an Andy Warhol and wins a bid of $50,000. His reaction is to cry, as Muniz embraces him. He feels this is recognition for his life, for his determination to start the association and for the dignity of his work.

If it makes it difficult for Tiao to return to the garden, well, it was difficult to be there in the first place. Last year, I saw a documentary named “Scrappers,” about the men who travel the alleys of Chicago seeking scrap metal. There is also Agnes Varda’s great film “The Gleaners and I” (2000), about those who seek their livings in the discards of Paris. When we see men going through the cans in an alley, some of us tend to distrust and vilify them. They are earning a living. They are providing a service. Incredibly, they’re sometimes called lazy. Documentaries like these three help us, perhaps, to more fully appreciate our roles as full-time creators of garbage.

*Originally, this review incorrectly identified the woman who cooks as Zumbia. Irma is the cook. We have corrected the text.—Editor