The image of Benito Mussolini has been shifted over the years toward one of a plump buffoon, the inept second fiddle to Hitler. We’ve seen the famous photo of his ignominious end, his body strung upside down. We may remember his enormous scowling visage trundled out on display in a scene from Fellini’s “Amarcord.” What we don’t envision is Mussolini as a fiery young man, able to inflame Italians with his charismatic leadership.

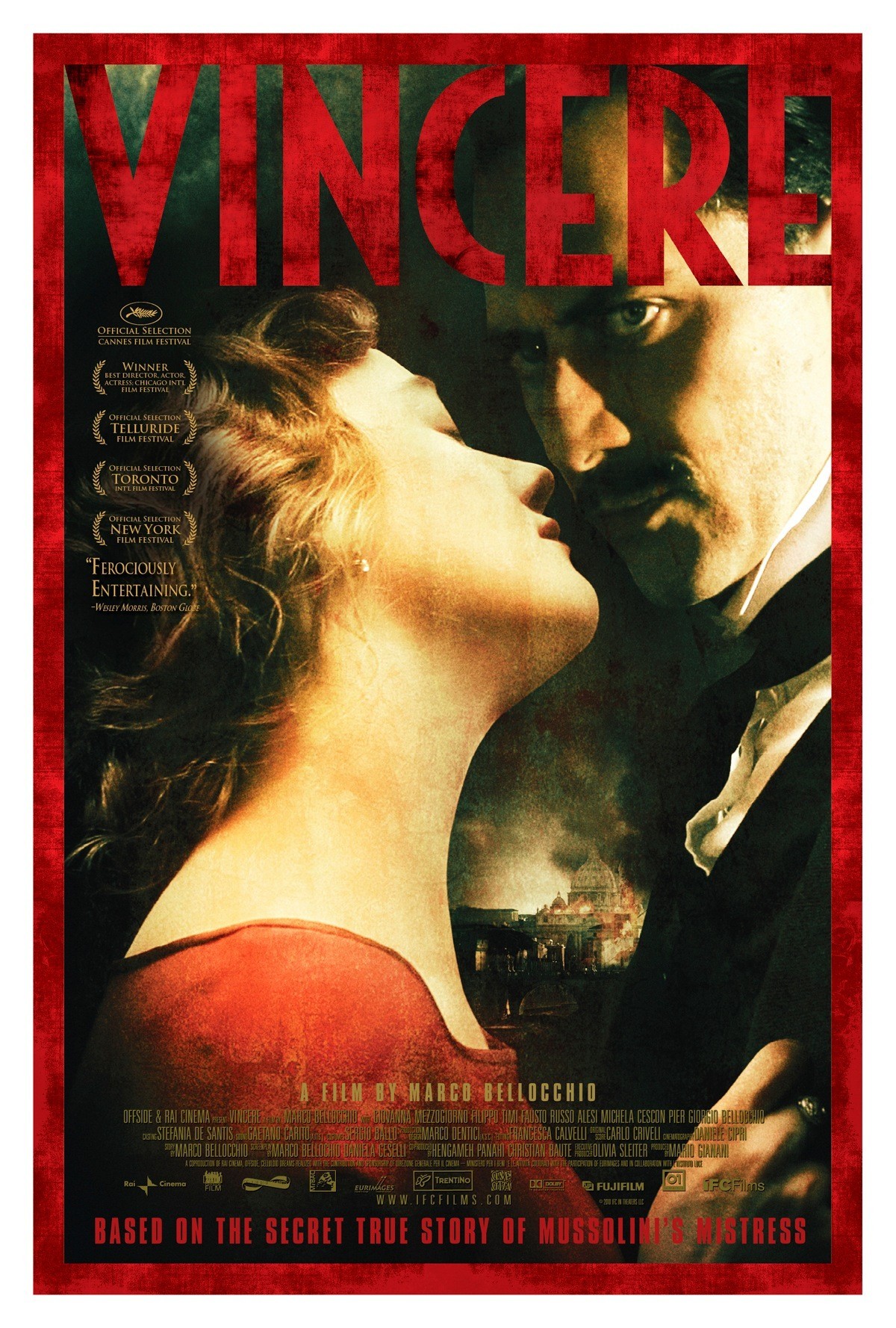

That’s the man who fascinates Marco Bellocchio, and his “Vincere” explains how such a man could seize a young woman with uncontrollable erotomania that would destroy her life. She was Ida Dalser (Giovanna Mezzogiorno), at first his lover, later his worst nightmare. When she first saw him before World War I, he was a firebrand, dark and handsome, and she was thunderstruck. For Ida, there was one man, and that was Benito (Filippo Timi), and it would always be so.

Her feelings had little to do with his politics. “Vincere” might have been much the same film if Mussolini had been a Christian Democrat. Her feelings spring from a fierce love, which at first is mutual. That he is filled with ideas and ambition make him all the more attractive, but does she even care what those ideas are? She supports them as a matter of course, selling all she has to support his party newspaper.

They have a son. He leaves to serve in the Italian army in the war. He is possibly lost in combat. She doesn’t hear from him. It is an old story. When he reappears after the war, it is impossible for him to lie low; he is Mussolini, in his own mind the chosen one. They are reunited briefly, and the old passion is there. Then she discovers he has a wife. A mistress and a child are decidedly… inconvenient for him.

It is revealing how inconvenient Mussolini considers them, and how his values were shaped by bourgeois Catholicism despite his politics. As he makes a strategic alliance with the Vatican, he cannot imagine, and he doesn’t believe the public can accept, a leader with a mistress. His wife Rachele (Michela Cescon) certainly cannot. We might assume Ida could be hidden away or even kept in plain sight, like his friend Hitler’s Eva Braun. But no.

If Ida had been capable of staying out of sight and staying quiet, some accommodation can be imagined. A discreet government pension. A home in a city distant from Rome. That is not to be. She considers Mussolini a demigod, and with all the passion of a woman defending her child, she wants her son — hers! — to be acknowledged before all the world as the great man’s offspring and heir.

Bellocchio, once himself a fiery young artist (“Fists in the Pocket”), now a legend of the generation of Bertolucci, is concerned with Mussolini’s fascism primarily as backdrop. His film is focused on Ida. The last time she sees him in the flesh is the last time we do. Thereafter he’s seen only in newsreels — a convenient way for Bellocchio to age and fatten him.

We see Ida’s marginal, scorned existence. We see her enacting life scenes that could be staged in opera: She bursts upon Mussolini during public appearances, dragging along the hapless boy as evidence of Benito’s heartlessness. The boy himself is bewildered, less concerned with his purported father than with his daily existence with a mother consumed by her obsession.

Was she mad? The term is “erotomania,” defined by the conviction that someone is in love with you. It can be a complete delusion, as in the case of celebrity stalkers. But it is not delusional if that person was in love with you, held you in his arms night after night, and gave you a son. In “Vincere,” the fascists instinctively protect Mussolini. When Ida appears in public places, she is surrounded and taken away without Benito even needing to request it. Finally, shamefully, she is consigned to an insane asylum, and the boy is locked up in an orphanage. She becomes a familiar type: The poor madwoman who is convinced the great man loves her and fathered her child. She writes letters to the press and the pope; such letters are received every day.

Bellocchio bases his film on the performance of Giovanna Mezzogiorno. She is one of those actresses, like Sophia Loren, who can combine passion with dignity. As Mussolini, Filippo Timi avoids any temptation to play with the benefit of hindsight. He is ambitious, hopeful, sometimes unaware of success. The film’s title, which translates as “victory,” reflects for much of the film a hope, not a certainty.

The film is beautifully well-mounted. The locations, the sets, the costumes, everything conspire to re-create the Rome of that time. It provides a counterpoint to the usual caricature of Mussolini. They say that behind every great man there stands a great woman. In Mussolini’s case, his treatment of her was a rehearsal for how he would treat Italy.