Few people were greater fans of The New Yorker cartoon caption contest than Roger Ebert. Out of an approximate 200 submissions, one received first place, though several more have been published online, both by Ebert and New Yorker cartoon editor Bob Mankoff. After Ebert’s death in 2013, Mankoff listed some of the funniest entries made by the late critic, and noted that the last one—written a week prior to his passing—was for the image of a chef lying in a coffin. Though Mankoff admitted that it didn’t rank among Ebert’s best captions, he imagined the critic would have quipped, “Hey, give me a break. Dying is easy, comedy is hard.”

It’s easy to see why people like Ebert would be so taken with the droll charm of New Yorker cartoons, which essentially serve as cultural criticism. They can accentuate the absurdities of everyday life with sketches that are at once spare and expressive, silly and sophisticated. There’s no doubt that most critics who watch Leah Wolchok’s playful documentary, “Very Semi-Serious,” will find the array of cartoonists interviewed eminently relatable, in part because their cherished work will never pay the bills, thus rendering day jobs a necessity. There’s a particularly poignant cartoon where a boss matter-of-factly informs his employee that, “We have a new financial model where you don’t get paid anything.”

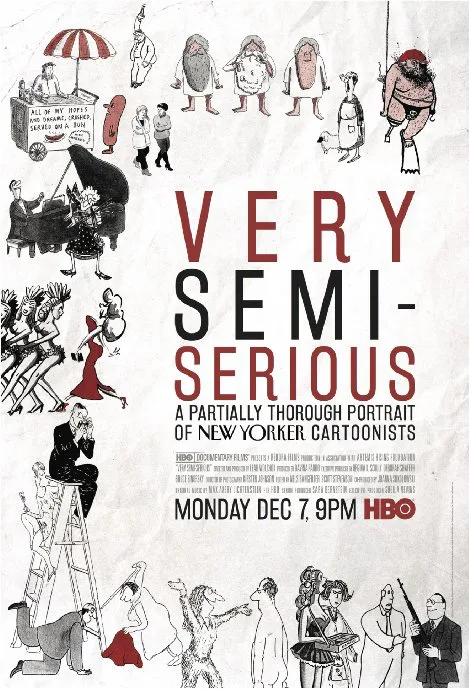

Catnip for writers and humorists of all stripes, Wolchok’s film provides delightful breakdowns of various cartoons, examining the comedic rhythm of their design and detail. Occasionally the camera will pan down an elaborate drawing before lingering on a succinct caption of deadpan understatement. Unlike “Wordplay,” Patrick Creadon’s 2006 profile of New York Times crossword puzzle editor Will Shortz, “Very Semi-Serious” is not limited to the story of one man and his many admirers. At a brisk 83 minutes, the film does live up to its tongue-in-cheek subtitle promising “a partially thorough portrait of New Yorker cartoonists,” though Wolchok does an admirable job of providing amble screen time for numerous artists—both veteran and aspiring—while enabling us to survey their distinctive styles (the most iconic of which belongs to Gothic satirist Charles Addams).

Part of the New Yorker cartoons’ appeal lies in their timelessness. It’s startling to observe how a cartoon from the publication’s inaugural year of 1925—juxtaposing an ape hanging from a branch and a commuter clutching the handle of a subway train, accompanied by the caption, “700,000 years of progress”—could’ve been dreamed up yesterday. Mankoff refers to one new cartoonist, Ed Steed, as a genius in how he creates imagery that could’ve resonated in any era. Oftentimes his drawings don’t require a caption in order to elicit a laugh. The same cannot be said of Liana Finck, another fresh-faced, soft-spoken talent whose submissions rely heavily on her own handwritten captions. Though she has difficulty in getting her work published, one hopes to see much more of it in The New Yorker, since it’s among the funniest featured in the film. I especially love her sample sketch entitled, “The Wisdom of Used Tissues,” in which crumbled kleenexes lie on the ground, wistfully musing, “At least we’ll have our memories.”

At the center of the film, of course, is Mankoff, who resembles a grayer yet cheerier Joel Coen, and is credited with keeping his department relevant after taking over as cartoon editor in 1997. It was his idea to make the cartoons intergenerational by giving young people the chance to contribute their work, which tends to be inspired more by “Ren and Stimpy” than “Goofus and Gallant” (Mankoff asks one artist to dial back on the seemingly crack-fueled expressions of his characters). The emergence of female voices has also been key in subverting the publication’s predominantly male gaze. In an excerpt of archival footage, the head of twentysomething cartoonist Roz Chast is seen bobbing its way through a sea of men at a staff party, an indelible image worthy of its own caption. Chast has since become one of The New Yorker’s most prolific cartoonists, with taboo-busting peers like Emily Flake following in her footsteps. Flake considers the bullying and alienation she endured in her youth not only preparation for her career as a cartoonist, but a pre-requisite.

Nothing provides better fodder for comedy than the unescapable seriousness of life. Though no cartoons ran in the issue following the 2001 terror attacks, the second post-9/11 issue featured a classic sketch by Leo Cullum, in which a badly dressed man is told by a jovial woman, “I never thought I’d laugh again, but then I saw your shirt.” Aside from minor slip-ups, such as two similar cartoons running back-to-back, there are no scandals to speak of in the cartoon department’s history, at least according to the documentary. No mention is made of Charlie Hebdo, though viewers will likely speculate about whether the free speech championed by publications like The New Yorker will be compromised by the threat of terrorism. My guess is that it won’t at all, considering editor David Remnick’s response to a colleague cautioning that a cartoon parodying The Last Supper will receive hate mail: “Who cares?”

Though the subjects remain acutely aware of Wolchok’s camera throughout, there is one instance of unguarded emotion where Mankoff and his wife recall the recent death of their son. Tears begin to flow as they explain that their recent change of houses was motivated by their need to escape painful memories that existed in every signifier of the past. For nearly a century, The New Yorker cartoons have provided readers with the sort of visual diversions that have made it possible for life to continue to be lived, even in the wake of unthinkable despair. We seek solace in them, and so do their creators. In one classic cartoon, a man is guided out of his bedroom by the Grim Reaper, while his wife calmly replies, “Think of it as one less thing to worry about.” Death will eventually guide us all out the door, but that doesn’t mean we can’t have the last laugh.