A table, some chairs, many shadows reaching out into the unseen depths of an abandoned theater, and a long night of truth-telling.

These are the elements of “Vanya on 42nd Street,” a film which reduces Chekhov’s “Uncle Vanya” to its bare elements: loneliness, wasted lives, romantic hope and despair. To add elaborate sets, costumes and locations to this material would only dilute it.

The movie is the result of a five-year theatrical experiment.

The stage director Andre Gregory and the actor Wallace Shawn, who collaborated on “My Dinner with Andre” (1981), gathered other actors and began to perform “Vanya” here and there around New York, in small theaters or even in the apartments of friends. Any room would do.

They were more interested in the words, using a translation by David Mamet that makes the dialogue both conversational and somehow more formal, more thoughtful, than ordinary conversation.

One night Louis Malle, the French filmmaker who made “My Dinner with Andre,” came to see the work in progress, and suggested that he film it. So the old friends were reunited after a decade, and the opening scenes of “Vanya on 42nd Street” suggest the earlier film, as the principals make their way through the streets of Manhattan for a rendezvous. We see the actors arriving for work, carrying paper cups of coffee, making their way into the New Amsterdam Theater, where faded glory waits under a layer of dust and cast-about furniture.

The play starts before we realize it. One moment we are settling in with Gregory and a few other observers for a rehearsal, and the next the lighting has been subtly altered, and the big old table on the stage has become a sitting room on a rural estate in Russia.

The characters are among the most familiar in literature.

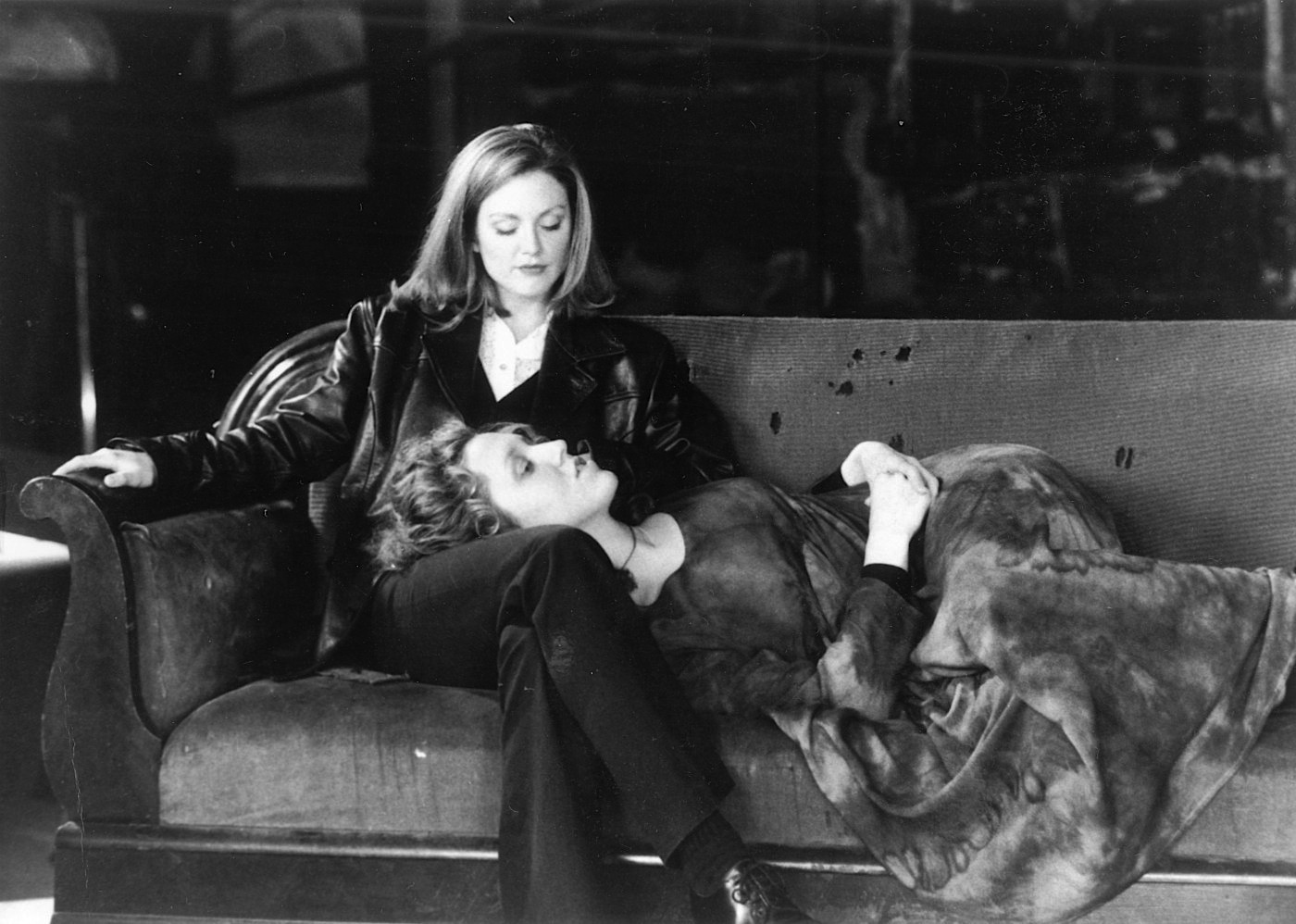

Uncle Vanya (Shawn), now in his 40s, has for many years managed the estate for Serybryakov (George Gaynes), the husband of his late sister. This man has now returned to the estate with his young wife Yelena (Julianne Moore). Vanya hates Serybryakov – feels he has wasted his life making money for him – and feels a secret passion for Yelena. He is enraged that Serybryakov has returned with plans to sell the estate and make its residents homeless.

Also in the household are Sonya (Brooke Smith), Vanya’s sister; Maman (Lynn Cohen), their old mother; Marina (Phoebe Brand), a family retainer; and the sad, haunted figure of Dr. Astrov (Larry Pine), a neighbor who comes many nights to sit and drink himself into oblivion. The emotional connections are these: Serybryakov feels himself too old for the young Yelena; Vanya feels himself the right age for her, but cut off by poverty; and poor quiet Sonya has nursed a quiet love for Dr. Astrov for years.

The subject of the play is, What use should we make of our lives? The deeper subject is the fear of the characters that they have wasted theirs. Serybryakov is a gambler and a wastrel, who has tossed away the fortune he obtained from Vanya’s dead sister. Yelena has become the wife of this hollow man. Vanya has spent his life in an obscure corner of the world, managing an estate whose owner can hardly be bothered to visit it. Astrov is lost in alcohol, Sonya dares not even speak of her love for him, and all of them go around and around, repeating the same patterns, nursing the same resentments, until something must break.

Something does, in the famous scene where Vanya picks up a revolver and threatens to end the charade with bloodshed. But there are quieter moments in the play that are even more violent, as, in the middle of the night, the characters finally tell each other what they truly dream, love, and fear.

Malle, whose films are usually much larger (“Atlantic City,” “Pretty Baby,” “Au Revoir, les Enfants”) shows again, as he did with “My Dinner with Andre,” that he is the master of a visual style suited to tightly-encompassed material. There is not a shot that calls attention to itself, and yet not a shot that is without thought. From time to time, he draws back from the drama to remind us of the watchers in the theater, and has Andre Gregory, the director of the stage version, murmur a few quiet words of comment or explanation to his guests. Gregory’s attitude – absorbed, fascinated, unobtrusive – sets the tone for how to watch the play, and Malle’s camera goes for exactly the same tone.

The title “Vanya on 42nd Street” suggests some kind of jazzy updating of Chekhov, a modern-dress revisionism. The film is just the opposite. Although the actors’ clothing and their cardboard cups of coffee are admissions that the production is taking place right now, the drama seems to take place outside time. It is not about characters in 19th century Russia, but about anyone who feels their lives have been placed on hold – that some “necessity,” such as a family responsibility or a financial need, has required them to spend years going through motions that are irrelevant to what they really feel and need.

All of the characters have thrown away their lives, but none is more agonized about it than Vanya. Wallace Shawn’s performance in this role has been criticized in some quarters because the actor is, well, too comic, or too much of a tortured nebbish, to be a Chekhovian hero. I felt the opposite. Shawn is so specific, so entirely himself, that he brings Vanya right down to the bottom line: He is not great, not brilliant, not smooth, not lucky with women, but by God he has feelings, too! And among them is the conviction that he has been dealt a rotten hand.

At the end of the film, there is a long monologue by Sonya, the quiet one whose family role has been as a passive background presence. At last she says what she thinks. The scene is wonderfully handled by Brooke Smith, who gives expression to what Sonya hopes: That if there is nothing to be done in this life, at least we may find a perfect mercy beyond the grave. The film ends with not much conviction that this will happen – but at least the characters can, once again, dream.