“Uncle Buck” attempts to tell a heart-warming story through a series of uncomfortable and unpleasant scenes; it’s a tug-of-war between its ambitions and its methods. It stars John Candy as the title character, a big-hearted softy who has been drifting through life as an unemployed horse-racing fan. Buck’s brother Bob calls one night with an emergency: Bob’s father-in-law has had a heart attack, and they need someone to house-sit and watch the kids for a few days.

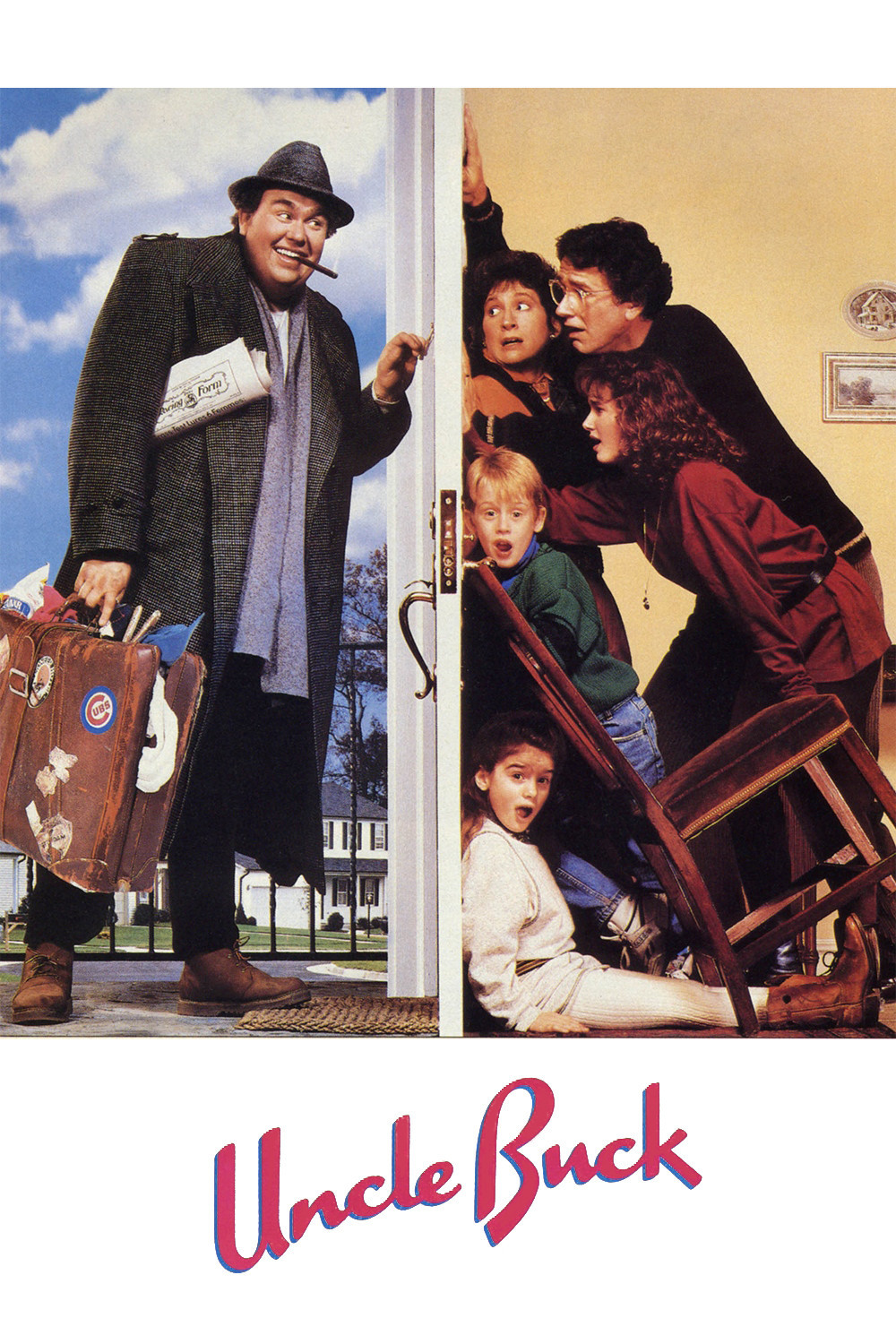

Buck agrees, and arrives a few hours later, driving a big gas hog that leaves billowing clouds of exhaust fumes in its wake. (It’s often a sign of desperation in a movie when a character is given a funny car, and “Uncle Buck” is no exception.) At his brother’s expensive home in the northern suburbs of Chicago, he finds three kids uneasily waiting for him: a cute little boy and girl, and a glowering 15-year-old (Jean Kelly) who resents him just as she resents, apparently, every facet of her existence.

The parents hurry off to Indianapolis, to clear the way for the predictable plot, in which shabby old Uncle Buck tries his best to be a good parent, and eventually wins the love of all of the kids, although not without some hard times in between. Although Buck attempts to project serenity around the house, he has heavy matters weighing on him – not the least of which is his relationship with his girlfriend (Amy Madigan), who owns a tire store and is fed up with Buck’s wayward life plan.

What happens in “Uncle Buck” is not hard to anticipate, but what’s surprising is how many wrong notes are sounded by the story, written and directed by John Hughes. Often it’s a matter of tone. The rebellious teenager is too angry sometimes, too sharp to be sympathetic. A promiscuous neighbor (Laurie Metcalf), who comes over to make a play for Uncle Buck, is such a caricature that she doesn’t amuse, she repels.

In one particularly uncomfortable scene, Uncle Buck confronts a grade-school teacher and flips her a quarter (“to go downtown and have a rat gnaw that growth off of your face”). The scene is handled with such a mean spirit that any possible humorous effect is lost, and we simply feel had afterward.

We also feel uneasy, most of the time, while Uncle Buck attempts to deal with the 15-year-old girl’s relationship with her boyfriend. Buck delivers one long speech in which he offers to shave the lad’s kneecaps with an ax, and a little later he comes after him with a power drill, and then locks him in a car trunk. Sure, the kid is no good, but these scenes seem borrowed from some black comedy from a bloodier universe than good old Buck seems to inhabit.

Many of the elements in “Uncle Buck” represent familiar territory for Hughes, who often deals with teenagers and almost always shoots in Chicago’s northern suburbs.

Perhaps the title character in “Uncle Buck” was inspired by the hapless, lovable character played by Candy in Hughes’ 1987 comedy, “Planes, Trains and Automobiles.” This could be a glimpse of the same man’s life when he’s not on the road.

But Hughes is usually the master of the right note, the right line of dialogue, and this time there’s an uncomfortable undercurrent in the material.

The movie is filled with good intentions and good feelings, but they seem to conceal another side of Uncle Buck – a side that makes the movie feel creepy and subtly unwholesome.