This movie is a loose remake of a 1973 French crime drama written and directed by Jose Giovanni, who wrote a handful of classic genre pictures, including Jacques Becker’s prison-break picture “Le Trou,” Alain Corneau’s gangster-on-the-run story “Classe tous risques” (both 1960) and Jean-Pierre Melville’s one-last-caper “Le Deuxieme Souffle” (1966). Giovanni’s original was a tense, lean narrative of a paroled con dogged by an old enemy, a cop with a grudge. This film, directed by Rachid Bouchareb, best known in this country for his “Indigènes” (aka “Days of Glory”), about North African soldiers fighting for France in World War II, makes the story a bit baggier, and, in a reach for contemporary significance, changes its setting to contemporary New Mexico and makes its paroled criminal a convert to Islam.

In this update, the viewer knows things are going to end badly from the opening shots. One of the film’s characters is seen dragging an inert body over a desert landscape. Then, in a long shot, he’s seen smashing the body’s head with a rock while screaming. The perspective reminded me of a similar death-seen-from-a-great distance scene, in Abderrahmane Sissako’s extraordinary 2014 “Timbuktu,” but where Sissako’s scene showed a quiet, implacable assurance, Bouchareb’s presentation has a slight ring of manipulative dynamics, and overdetermination. This feel persists over the course of many perfectly-framed vistas, including a shot of Brenda Blethyn standing in a doorway that is practically begging the viewer to compare it to “The Searchers.” But Blethyn’s recognizable presence also constitutes a godsend of sorts: when this film’s excellent actors are given things to do, Bouchareb’s heavy-handedness is easier to ignore.

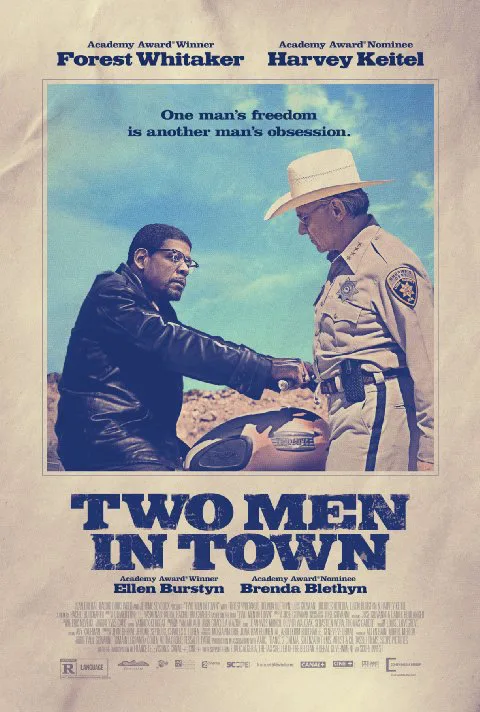

Blethyn’s character is a parole officer. Forrest Whitaker plays Garnett, out three years early from a twenty-year-plus sentence; seems he killed a deputy during his gang-banger times. Harvey Keitel is Agati, a humane but exceptionally businesslike sheriff who has an extreme grudge against Garnett. The movie takes its time with these characters. Garnett, praised early on by his spiritual adviser on having learned to control his anger (there’s the first-act gun-mention you always hear that Chekhov quotation pulled out about), rides around on a motorbike enjoying his newfound freedom while Agati seethes and ponders what he’s going to do about this new problem preying on his mind. Blethyn’s character gives Garnett the old tough-not-quite-love treatment, bristling when he ingenuously boasts to her about a date with a woman he’s about to go on. “Tell her the truth,” she bluntly advises him. And he does, eventually. But once Agati starts harassing him, and once an old criminal associate (Luis Guzman) starts trying to lure him back into the fold, Garnett starts coiling up into himself more and more. An explosion is bound to happen.

The suspense is spiced up here by the culture clashes implicit in the environment and explicit in some of the characterizations. Early in the film Keitel’s sheriff asks Blethyn’s character to stop by a barbecue celebrating the return home of some troops who’ve been serving in Afghanistan. Garnett’s devotion to his newfound faith doesn’t impress Agati at all: in fact it seems to deepen his resentment of the character. What’s odd about “Two Men” is the fact that after establishing all of this material relative to character, Bouchareb, who co-wrote the adaptation with Olivier Lorelle and Yasmina Khadra, allows it to all fall away. The story builds to a climactic confrontation, but not the one, perhaps, that we’ve been expecting, and then ends on a frustratingly indeterminate note that has little to do with the issues the movie went to the trouble to raise in the first place. As exceptional as the acting in the picture is, and it is wonderful—Whitaker and Keitel are as inventive and surprising as they’ve been in years, and the supporting roles played by the likes of Ellen Burstyn and Stan Carp are well-sketched—it can’t entirely lift the movie from the rut it has all but plowed into by the end credits.