I believe Sandra senses something is damaged about Leonard. “Two Lovers” never puts a word to it, although we know he’s had treatment and is on medication. It’s not a big showy mental problem; lots of people go through life like this, and people simply say, “Well, you know Leonard.” But Sandra does know him, and that’s why she tells him she not only loves him, but wants to help him.

Leonard (Joaquin Phoenix) is focused on his inner demons. His fiancee left him — dumped him –and he has moved back to his childhood room, still with the “2001” poster on the wall. He makes customer deliveries for his dad’s dry cleaning business. Sandra (Vinessa Shaw) is the daughter of another of another dry cleaner, in the same Brighton Beach neighborhood of Brooklyn. Her father plans to buy his father’s business, and both families think it would be ideal if Sandra and Leonard married.

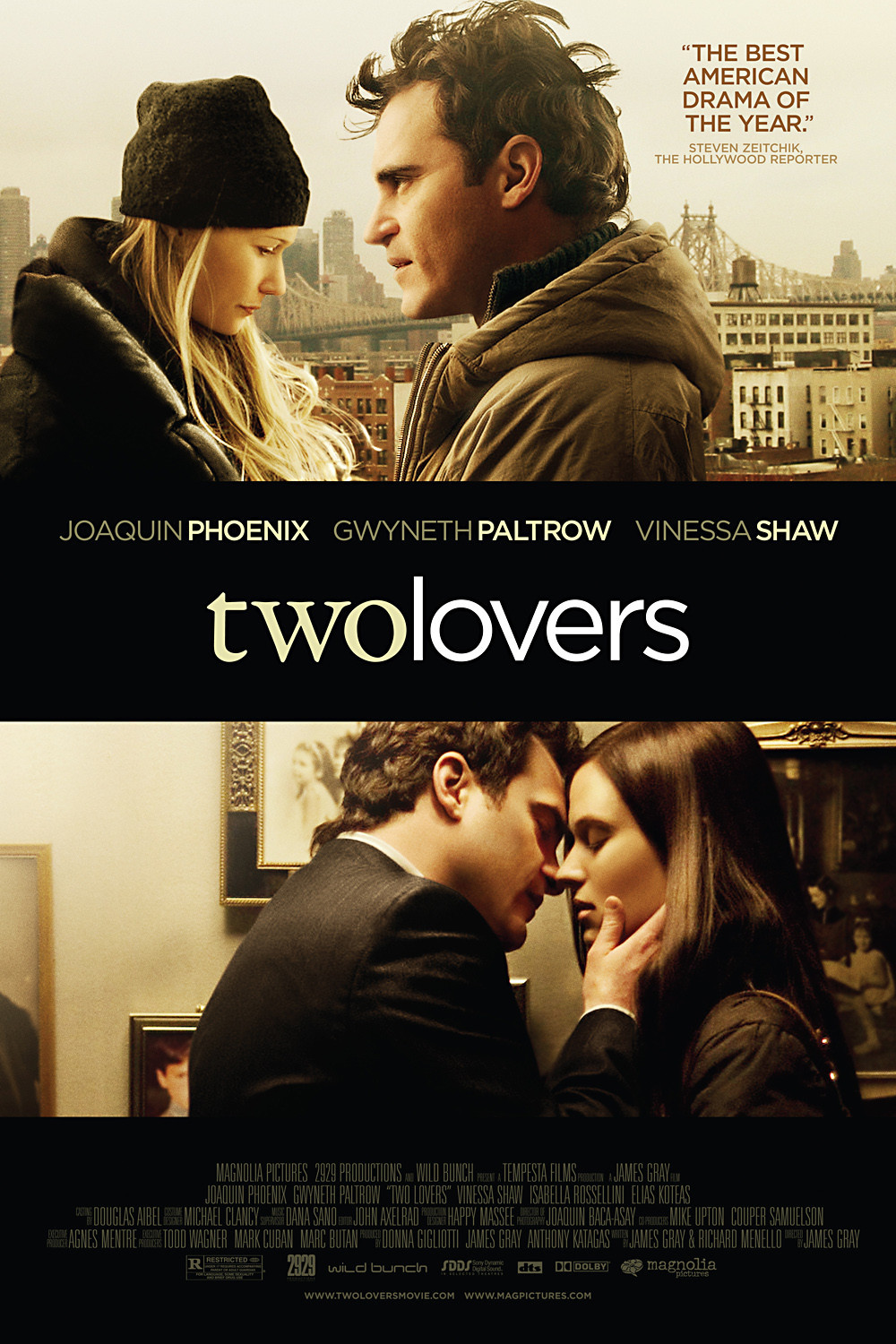

But Leonard meets Michelle (Gwyneth Paltrow) and is struck by the lightning bolt. She’s blond, exciting, and in his eyes, sophisticated and glamorous. She seems to like him, too. So a triangle exists that might seem to be the makings of a traditional rom-com from years ago. James Gray‘s “Two Lovers” is anything but traditional, romantic or a comedy. It is a film of unusual perception, played at perfect pitch by Phoenix, Shaw, Paltrow and the other actors. It is calm and mature. It understands these characters. It doesn’t juggle them for melodrama, but looks inside.

Michelle is the kind of person many of us become fascinated with at some unwise point in our lives. She has enormous charm, a winning smile, natural style. But she is haunted. Leonard is blindsided to discover she has a married lover, and that she uses drugs. He is able, like so many men, to overlook these flaws, to misunderstand neediness for affection, to delude himself that she shares his feelings. Sandra, on the other hand, is pretty, and nice, but their families have known each other for years and Michelle seems to offer an entry into a new world across the bridge in Manhattan.

The particular thing about “Two Lovers,” written by Gray and Richard Menello, is that it utterly ignores all the usual cliches about parents in general and Jewish mothers in particular. Both Leonard and Sandra come from loving families, and both of them love their parents. Although Leonard sometimes seems to contain muted, conflicting elements of Travis Bickle and Rupert Pupkin, he tries to get along with people, to be polite, to be sensitive. That he is the victim of his own obsessions is bad luck. It’s painful watching him try to lead a secret life with Michelle outside his home, especially when her emergency demands come at the worst possible times.

Leonard’s parents are Ruth and Reuben Kraditor (Isabella Rossellini and Moni Monoshov), long-married, staunchly bourgeois, reasonable. Ruth of course wants Leonard to find stability in marriage with a nice Jewish girl like Sandra, but her love for him outweighs her demands on him — rare in the movies. Reuben is more narrow in his imagination for his son, but not a caricature. And Sandra’s father (Bob Ari) wants to buy the Kraditor business and likes the idea of a marriage but would never think of his daughter as part of a business deal. Everyone in the film wants the best for their children.

So the drama, and it becomes intense, involves whether Leonard’s demons will allow him to be happy. Michelle represents so many problems she should almost dress by wrapping herself in that yellow tape from crime scene investigations. She has a gift for attracting enablers. We meet her married lover (Elias Koteas), who turns out not to be an old lech, even if he is an adulterer. He’s essentially another victim, and a short, tense scene he has with Leonard provides private insights.

Here is a movie involving kinds of people we know, or perhaps have been. It’s the third film in which James Gray has directed Joaquin Phoenix (after “The Yards” and “We Own the Night“) and shows them working together to create a character whose manner is troubled but can be identified with. The whole movie is so well-cast and performed that we watch it unfolding without any particular awareness of “acting.” Even the ending, which might seem obligatory in a lesser film, is earned and deserved in this one.