The trouble with “A Man and a Woman,” I’ve always thought, is that in the real world love doesn’t happen like that. The trouble with love, I’ve always thought, is that in the real world it should.

Love is ever so much, more satisfactory in the movies, where every other kiss is framed by a sunset, and people are always running toward each other in slow motion, their arms outstretched, while in the background the tide comes in, or goes out, or keeps busy, anyway.

I think maybe Stanley Donen was trying to come to grips with this problem of love in the movies when he made “Two for the Road.” Donen has always been a consistently intelligent maker of entertainment for mass audiences. The best Hollywood musical ever made, “Singin' in the Rain,” was his. A Donen movie, whatever its faults, always looks good on the screen. He likes beautiful colors, perfect photography, quick editing. Donen, in fact, makes almost as much of a fetish out of technical quality as Andy Warhol doesn’t.

But just because a movie looks good doesn’t mean it has anything to say. Unless you’re a hippie you can’t make a love story out of chanting “love, love” all the time. But if you’re going to make a love story at all, you have to recognize that your lovers have to look good. Audiences identify with the lovers on the screen, and who wants to identify with Ma Kettle’s suitor?

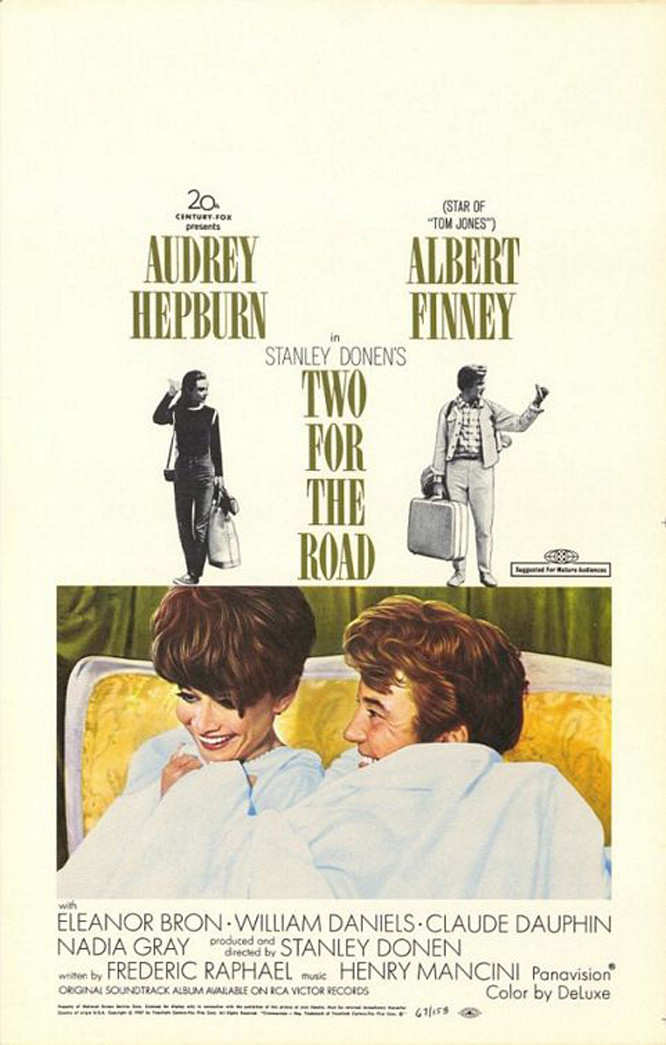

So Donen did all of the necessary things. He cast Audrey Hepburn and Albert Finney, two uncommonly attractive people, as his lovers. He shot in brilliant colors. He used a screenplay by Frederic Raphael which cleverly and amusingly leaps back and forth in time, catching the couple at various points during their courtship and marriage. And he borrowed a musical comedy trick, putting all the episodes “on the road,” as Finney and Hepburn hitchhike, drive and fly around Europe.

That makes a pretty corny love story, right? Audrey Hepburn and Albert Finney off on the road, he a brilliant architect, she a beautiful woman, they working their way up from poverty to the jet set, we sitting amazed before all this splendor. To make it complete, throw in some stunt men, racing drivers, horses, kids, and another sunset or two.

But Donen doesn’t settle for that. He gets inside the natures of his lovers, and he examines what happens after they fall in love, get married, have a child, and age 10 years. These are things that happen to even the most lovestruck couples, and perhaps we should be grateful that Shakespeare spared us Romeo and Juliet on Social Security. The marriage gradually loses its novelty and charm; the love gradually transforms itself into a deep and weary familiarity; the child is as much a burden as a treasure, and the wife finally leaps into an adulterous affair. “Why is it,” Finney asks Hepburn, “that making love is always better when it doesn’t mean anything?”

There are some very funny scenes, particularly when Finney and Hepburn tour Europe with an Incredibly organized American couple and their hateful, obnoxious, spiteful little girl. The scenes with Audrey’s temporary French lover (played with such coolness by Georges Descrieres that you’d like to mash a grapefruit in his mug) are handled honestly, and are painful. “Too bad we never met,” Descrieres tells Finney the morning after. “Yes,” says Finney, “then you could have had the pleasure of committing adultery with a friend’s wife.”

Donen knows what he is doing, and does it very well. This is a slick, entirely professional, very smooth movie – but it is just because Donen and his associates are seasoned craftsmen that they never stoop to the obvious. They make “Two for the Road” two things: a Hollywood-style romance between beautiful people, and an honest story about recognizable human beings. I’d call it “A Man and a Woman” for grown-ups.