Before a concert, the orchestra members warm up by playing snatches of difficult passages from familiar scores. “Twilight” is a movie that feels like that: The filmmakers, seasoned professionals, perform familiar scenes from the world of film noir. They do riffs, they noodle a little, they provide snatches from famous arias. But the curtain never goes up.

The reason to see the film is to observe how relaxed and serene Paul Newman is before the camera. How, at 73, he has absorbed everything he needs to know about how to be a movie actor, so that at every moment he is at home in his skin, and the skin of his character. It’s sad to see all that assurance used in the service of a plot so worn and mechanical. Marcello Mastroianni, who in his humor, ease and sex appeal resembled Newman, chose more challenging projects at a similar stage in his life.

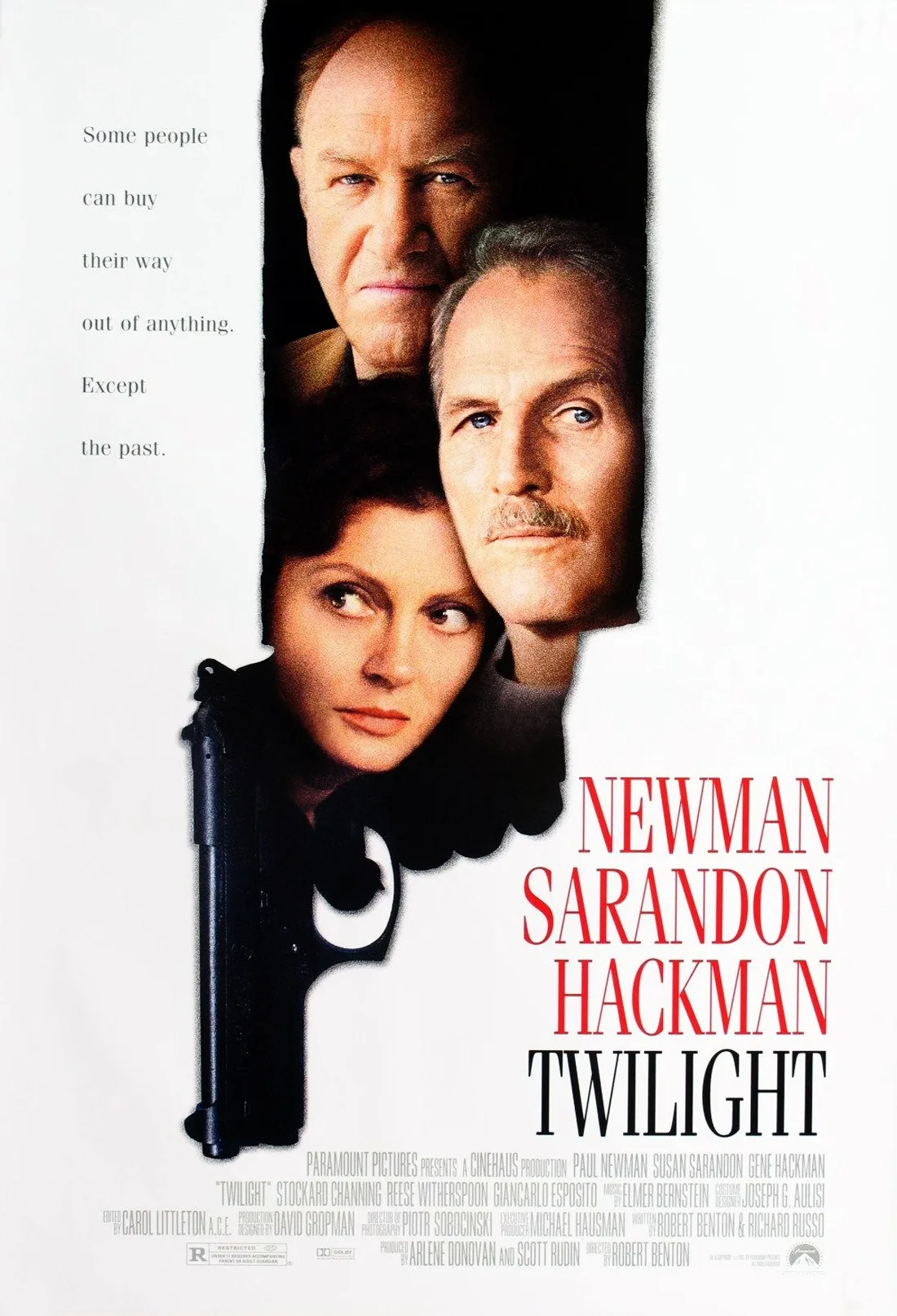

The other veterans in the cast are Gene Hackman, Susan Sarandon and James Garner. They know as much about acting as Newman does, although the film gives them fewer opportunities to display it. Garner, indeed, is the man to call if you need an actor who can slip beneath even Newman’s level of comfortability. But the movie’s story is too obvious in its message, and too absurd in its plotting.

The message: The characters are nearing the end of the line. They know the moves but are losing the daylight. “Your prostate started acting up yet?” Garner asks Newman. After Newman’s detective character is shot in the groin, the rumor goes around that he’s no longer a candidate for the full monty. What kind of a private eye doesn’t have any privates? For all of the characters, this is the last hurrah, and that’s especially true for Hackman’s, who is dying of cancer.

The plot: Harry (Newman), is described as “cop, private investigator, drunk, husband, father.” He has failed at all of those roles, and now, sober, broke, single and retired, he lives on the estate of Jack and Catherine Ames (Hackman and Sarandon), movie stars who are old friends. One day, Jack gives him a package to deliver. At the address he’s sent to, he discovers Lester, a dying man (M. Emmet Walsh) who someone has already shot. When he goes to the man’s apartment, he finds a newspaper clipping from 20 years ago, about the death of Catherine Ames’ first husband.

Were Catherine or Jack involved in the murder? Who was paying for the investigation? Harry wants to know. His trail leads him to Raymond Hope (Garner), a guy he knew on the force, who has made a lot of money as a studio security chief, and lives very well. It also leads to Catherine’s bedroom. He’s had a crush on her for years, but no sooner is there a romantic breakthrough than the phone rings: Jack is having an attack.

Jack discovers Catherine’s infidelity through the kind of clue (she’s wearing Harry’s pink Polo shirt) that seems left over from much older films. Harry knows Catherine was at the apartment where Lester died, because he smelled her perfume there. These are clues at the Perry Mason level, but the complete explanation, when it comes, doesn’t depend on them. It’s lowered into the film from the sky.

The screenplay, by director Robert Benton and his co-writer, Richard Russo, is bits and pieces. The movie appeals because we like the actors, not because we care about their characters. They’re like living beings caught in a clockwork mechanism. Also caught are several characters who hang around the periphery without enough to do: Stockard Channing as a cop Harry’s fooled around with in the past, and Giancarlo Esposito as a limo driver who turns up out of nowhere and becomes an inexplicable sidekick. Reese Witherspoon plays the sexpot Ames daughter.

Newman’s previous film, “Nobody’s Fool,” was also written and directed by Benton, based on a novel by Russo. It gave Newman one of his great roles, as an aging failure, still able to dream, hope and repair the wreckage of a life.

Here we have essentially the same character description, including the same roguish, unflagging sexuality, but the payoff isn’t a rich human portrait, it’s a contrived manipulation of arbitrary devices from old crime stories. Who cares?