“Triumph of the Spirit” goes to great lengths to establish a basis in fact. It is inspired by a true story, we are told, the story of a Greek Jew who survived the Holocaust because he was an expert boxer.

And it is the first fiction film to be shot on location in the death camp of Auschwitz. Every detail is accurate, down to the wooden shoes worn by the prisoners and the crusts of bread thrown onto their dinner plates.

I am impressed by the attention to detail demonstrated by the director, Robert M. Young, but I do not consider it a certificate of authenticity. Every serious story, especially one about a subject such as the Holocaust, must find its own inner truth, and on the inside, “Triumph of the Spirit” is hollow. It is never able to decide exactly what its story is saying, or should say. Blinded by the fact that the story is based on a man’s life, that it “actually happened,” the film seems to assume that the message is in the very accuracy itself. But at the end we feel confused and unsatisfied.

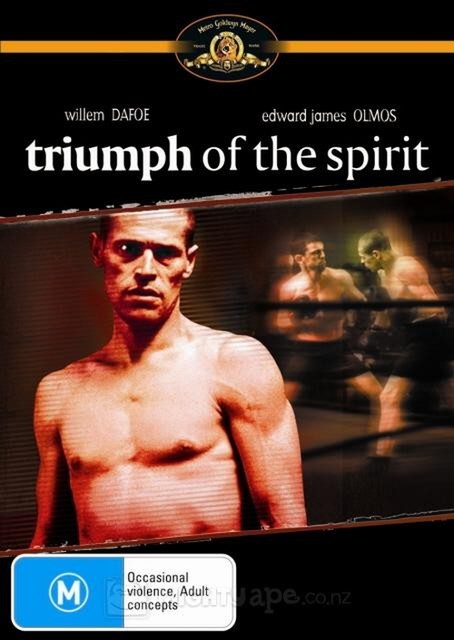

The film is the story of a man named Salamo (Willem Dafoe), a Greek shipped to Auschwitz, where he might have died if his Nazi captors had not discovered that he was a championship boxer. As an entertainment one evening, they set up a boxing match, which Salamo wins. They make him fight again. Money is wagered on the outcome, and soon Salamo’s fights are part of the Nazi social schedule; the officers gather once a week to eat, drink and watch prisoners pound one another.

Salamo, of course, is in an impossible situation. If he wins, he sends his opponent to certain death. If he loses, he himself dies.

It is this irony that enriches the sadistic enjoyment of his Nazi audiences. Salamo has another reason for fighting well, and that is the fate of his father in the camp – an old man (Robert Loggia) he hopes to keep from the gas chambers by using what small influence his stature has given him.

One of the camp’s gypsy prisoners (Edward James Olmos) is sort of a fixer in the camp, a slippery character who operates a shady black market based on bribery and persuasion. He becomes involved in Salamo’s attempts to help his father, but finally the father’s name appears on a list of those scheduled to disappear, and when Salamo asks what can be done, the gypsy replies, “Nothing, unless someone can be found to take his place.” At this point, in a more predictable movie, the son would have offered to take his father’s place. Salamo remains silent. Well, which of us would volunteer? The mystery at the heart of the Holocaust experience, as taught in countless books and films, is that an artificial situation was set up in which evil was the engine and there was no way to protest except by self-sacrifice.

Some chose to die. Many did not want to die, but died anyway.

A few, like Salamo, hid in a tiny crevice of the wall of insanity surrounding them, and survived. Salamo, we learn, won enough fights that he was still alive at the end of the war; he survived to tell his story, and this is the film of his story. But what does it mean? The title “Triumph of the Spirit,” with its obvious echo of the Nazi documentary “Triumph of the Will,” seems to indicate that Salamo’s spirit did triumph. But he survived at the cost of the lives of his opponents, who were fellow Jews. Is this a triumph, or merely an escape? The great inescapable problem of the Holocaust is that it defies being made sense of. That was the message of “Shoah,” the most profound film about the subject. The weakness of “Triumph of the Spirit” is that it takes a vast, humbling, infinitely sad subject and fits it into a fictional form – makes it into a fight movie, if you will.

There are several fight scenes, staged and choreographed like those in any other boxing movie, and the audience is enlisted to cheer for Salamo against his enemies. We are presumeably supposed to be relieved when he wins. Does this feeling not place us with the Nazis in his audience? Are the fights themselves not obscene? Did the filmmakers ever consider placing the fights offscreen, or dwelling on them less, and considering the implications of the situation Salamo finds himself in? Of course not, because the fictional formula was too seductive. And so what we finally have here is a boxing movie that tries to borrow meaning and authenticity from the great sorrow of the Holocaust. There are too many contradictions here to count.