“Tristan & Isolde” begins with bits of the same myth that has inspired works ranging from sword & sorcery movies (“Lovespell”) to operas by Wagner, and transforms them, rather surprisingly, into a lean and effective action romance.

The movie is better than the commercials would lead you to believe — and better, perhaps, than the studio expected, which may be why it was on the shelf for more than a year. Distributors who are content with the mediocre grow alarmed, sometimes, by originality and artistry: Is this movie too good for the demographic we’re targeting?

The movie dumps the magical love potion that is crucial in most versions of the story. This time, when Tristan and Isolde fall in love, it’s because — well, it’s because they fall in love. The story takes place in England and Ireland, circa the year 600. The Roman occupiers have withdrawn, leaving a disorganized band of English warlords feuding among themselves while King Donnchadh of the Celts (David O'Hara) rules England from Ireland.

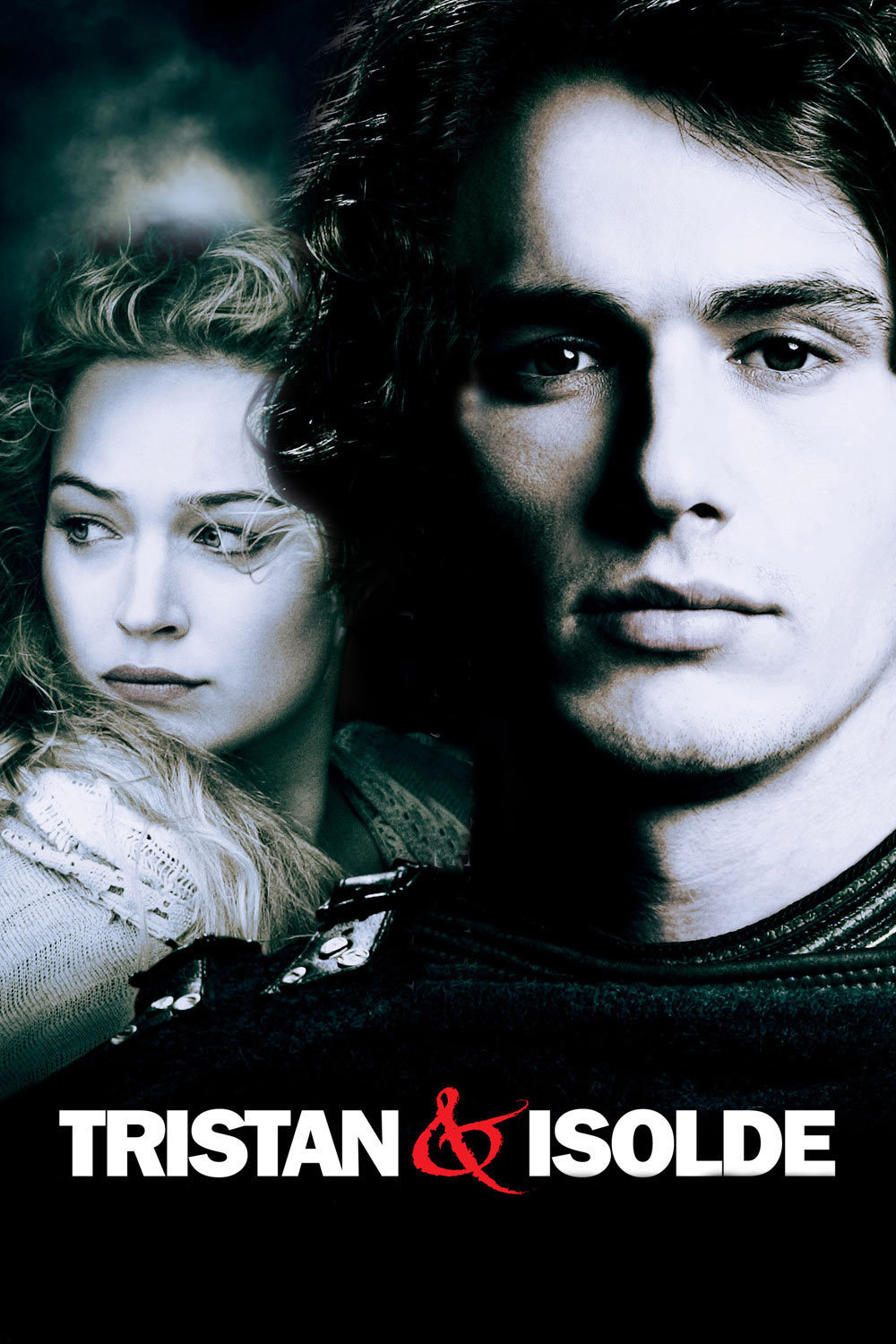

We meet Lord Marke (Rufus Sewell), wisest of the English rulers, who seeks to unite England and repel the Irish. He adopts the young Tristan (James Franco) and raises him as his son. Tristan leads Marke’s troops in setting a successful trap for Donnchadh’s overconfident raiders, but then is poisoned and falls into a coma resembling death.

Good thing the early Brits don’t believe in burial: They put Tristan’s body on a boat and push it out to sea, and a few days later, it washes ashore in Ireland and is found by the beautiful Isolde (Sophia Myles), daughter of Donnchadh. Tristan is alive!

All contrived, all melodramatic, yes, but seen in a rugged, muddy, damp, straightforward visual style by director Kevin Reynolds (“The Count of Monte Cristo,” “Waterworld“) his cinematographer, Artur Reinhart, and the production designer, Mark Geraghty. The knights and ladies don’t look like escapees from a Prince Valiant comic strip, but like physical, vulnerable, survivors of the conflicts left behind by the Romans.

The removal of magic from the story grounds it as a realistic power struggle, and although the device of mistaken identity is used to supply the heart of the plot, we can sort of see how things might have worked out that way.

I don’t want to betray details that may come as a surprise. So let me comment on what happens without revealing what it is. Tristan and Isolde, who love each other even though they are the children of bitter enemies, are put into an impossible situation that no one really intended for them. The Irish and English lords don’t even realize they know each other. Tristan is entered in a tournament and does not know what the prize is. Isolde thinks she knows what the outcome of the tournament means, but is mistaken.

And then, in a decision that is brave of Tristan and Isolde and maybe even braver of the filmmakers, they try to accept the reality they’re confronted with. When it is said that “this marriage will end 100 years of bloodshed,” they try to reflect, not without heartbreak, that the problems of two little people don’t amount to a hill of beans in this crazy world.

I’m going to remain vague about what happens next, except to say that it all becomes a great deal more involving than you might expect from a movie with castles and swords and horses and secret passageways. There are some fairly delicate scenes involving the deepest feelings of Lord Marke, Tristan and Isolde, and the actors don’t ratchet up the emotions but try for plausibility. They are grown-ups who face an emotional crisis as we think perhaps they might have. The writing of the crucial closing scenes doesn’t hurry for easy effects, but pays attention to what is meant, and what is felt.

Sophia Myles plays Isolde as the daughter of a king, raised by the king’s rules, true to her own emotions but true, too, to her duty. She doesn’t mistake Isolde for the heroine of a teenage romance. James Franco (the “Spider-Man” movies, “The Great Raid,” the upcoming “Annapolis“) is not a larger-than-life comic hero but a vulnerable warrior capable of doubts and schemes. Rufus Sewell (“Dark City“) plays Lord Marke as a statesman in a land of squabbling egos, who, when he discovers a surprising secret, is inspired not so much by jealousy as by the offense to his sense of the rightness of things.

One key to the quality of the movie may be the co-producers, Ridley (“Gladiator“) Scott and Tony (“Top Gun“) Scott. Ridley Scott wanted to direct this movie for 15 years, and although “Gladiator” may have pre-empted it on his schedule, it’s clear he was intrigued not only by the possibilities for action but by the impossible personal dilemma that faces Tristan and Isolde. By removing elements of magic and operatic excess from the story, the brothers Scott focus on what is, underneath, a story as tragic (and less contrived) as the one cited in the ads, “Romeo and Juliet.”