We’ve all heard of reverse engineering, but reverse engineering all the way to the 17th Century, that’s something else. There’s also the question of why one would want to do such a thing, given the state of indoor plumbing during that time. But a glory of the 17th Century that found no equal in the centuries since was the simply stunning painting of the Dutch master Johannes Vermeer. Vermeer’s unique visions of light have inspired and baffled artists for hundreds of years. The greatness of his paintings is twofold: the marvelous symmetry of his scenes, which do not depict epic moments in religion and history but rather (divinely, it seems) illuminated everyday-life doings, and the incredibly acute detail and color, almost a photorealism before its time.

To say, of Vermeer’s work, that there necessarily had to be some kind of trick to it, initially seems insulting to both the painter himself and to certain mythologized notions concerning artistic talent versus artistic genius and a lot of other things. But painting, like writing, like almost anything really, is not entirely a “creative” exercise; it’s also a technical one. No great novel ever got written by mere force of inspiration, nor has any great painting merely been willed into being. And so, for years, certain artists and scientists have devoted a great deal of time and energy to the question: “How did Vermeer do it?”

Tim Jenison, the inventor and entrepreneur (I well remember in my ’80s days as a consumer electronics journalist, how his software bundle called “Video Toaster,” which was the foundation for his fortune, shook things up in the world of pro AND home video) put himself in a unique position to find out. An inveterate tinkerer with an insatiable curiosity and the financial and temporal resources to execute a project with pretty much no practical benefit to anybody, Jenison was intrigued several years ago by the speculations, from artist David Hockney and academic Philip Steadman, that Vermeer’s vision had some kind of assist—possibly a camera obscura, a room-size optical device that projects a reflected image on to a wall. The supposition, then, was that the beautiful canvases the artist produced were in fact the result of something like a paint-by-numbers technique. Jenison decided to take things out of the speculative realm and actually try to physically recreate the conditions under which Vermeer worked, with the endgame being to produce a “new” Vermeer painting.

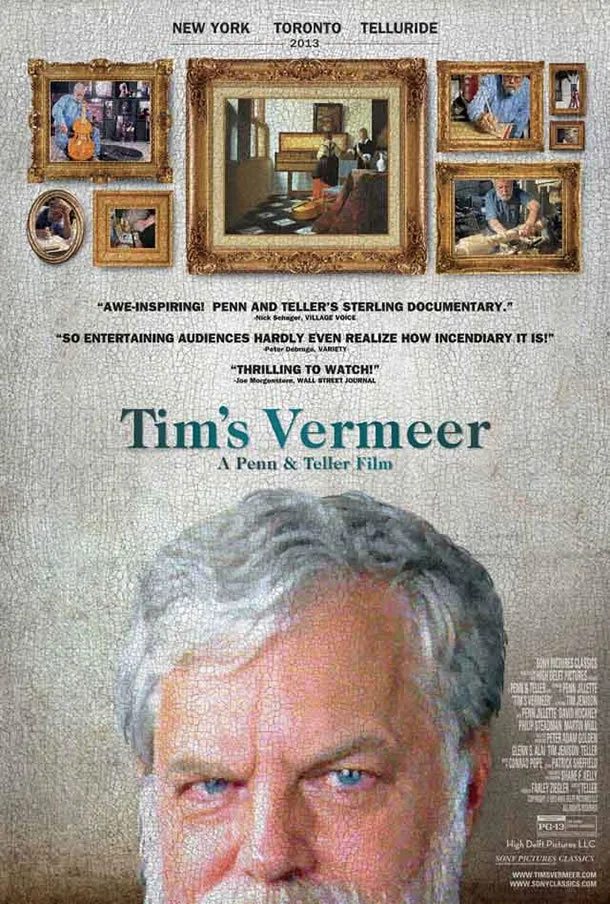

“Tim’s Vermeer,” directed by Teller and narrated by Penn Jillette—the performing duo that I dubbed “the philosopher kings of stage magic” about thirty years ago and am happy to note that the first part of the title still applies as they explore other modes and other media—chronicles Jenison’s years-long quest, during which time he learns Dutch, masters the art of pigment-making, and nearly asphyxiates himself. The movie is straightforward, brisk, engaging, and sometimes even moving.

One might feel wary that the movie, in depicting an attempt to duplicate Vermeer’s achievement, might also glibly undercut that achievement; but that’s not the point at all. Rather, “Tim’s Vermeer” wants to expand the audience’s understanding of what the actual practice of art is. One is reminded of Vladimir Nabokov invoking “the passion of the scientist and the precision of the artist.” This movie has that, and it also has a lot of joy, as the voluble Jenison shares his discoveries with Hockney and Pearlman. The men themselves seem to be reaching backward in time to commemorate an admiration and a kinship for Vermeer, who himself died in obscurity, his contribution to art unrecognized by his contemporaries.

There’s a slight thematic resemblance here to the well-known Jorge Luis Borges story “Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote,” in which a contemporary writer attempts to put himself in the mindset to exactly reproduce Cervantes’ early novel. But the resemblance actually points up the one thing “Tim’s Vermeer” doesn’t do in its hour and a half: it doesn’t concern itself with the aesthetic resonances of creating a Dutch Master’s work in the century of postmodern art. Given how juicy the movie is in and of itself, this elision rather makes one wish for a sequel.