Sun-Times Film Critic ‘The two worst years of a woman’s life,” writes Nell Minow, “are the year she is 13 and the year her daughter is.” There are exceptions to the rule; I recently attended a 13th birthday party at which daughter and mother both seemed to be just fine, thanks, but it is hard to imagine a worse year than the one endured by the characters in “Thirteen.” This is the frightening story of how a nice girl falls under the influence of a wild girl and barely escapes big, big, big trouble, by which I mean drugs, crime, unwanted pregnancies, and other hazards that some teenagers seem inexplicably eager to experience. That the horrors in this movie are worse than those found in the lives of most 13-year-olds, I believe and hope. It is painful enough to endure them at any age, let alone in a young and vulnerable season when life should be wondrous. But I believe such things really happen to some young teenagers, because at Sundance last January I met Nikki Reed, who co-wrote the screenplay when she was 13, and was 14 when she played Evie, the movie’s troublemaker. In real life Reed was the good girl; here, as a wild and seductive bad influence, she’s so persuasive and convincing I’m prepared to believe the movie is a truthful version of real experiences.

Evie is the most popular girl in the seventh grade, because of her bold personality, her clothes and accessories (mostly stolen), and her air of knowing more about sex than a 13-year-old should. The school’s value system is suggested by the fact that some of the students are working on a “project” about J. Lo.

One of Evie’s admirers is Tracy (Evan Rachel Wood), a good student who hangs around with a couple of unpopular girls and wants to trade up. Evie is cruel to her (“Call me.” she says, and gives her the wrong number). But when Tracy steals a purse and hands over the money, Evie takes her on a shopping spree and soon the girls are such close friends that Evie has, essentially, moved into Tracy’s room.

Tracy lives with her divorced mother Melanie, played by Holly Hunter in a performance where the character vibrates with the intensity of her life. Melanie lives in a sprawling house she can’t afford, inherited from a marriage with a husband who is behind on his child support; she runs a beauty salon in her kitchen, and her house seems to be a drop zone for friends, acquaintances, their children and their needs (“A $2 tip,” she complains after one mob leaves, “and they ate half the lasagna.”) Melanie is a recovering alcoholic, hanging on to AA for dear life, and with a boyfriend named Brady (Jeremy Sisto) who is in the program, too, although Melanie has painful memories from when he wasn’t. Melanie is sober, but it would be fair to say her life is still unmanageable, and although she loves Tracy and protects her with a mother’s fierce love, she’s clueless about what’s going on behind that bedroom door.

Evie’s history is often described but somehow never very clear. She lives with someone named Brooke (Deborah Kara Unger), who is not quite her mother, not quite her guardian, allegedly her cousin, more like her spaced-out roommate. Evie tells stories of violence and sexual abuse when she was young, and while we have no trouble believing such things could have happened, it’s impossible to be sure when she’s telling the truth.

Although Evie is trouble enough on her own, she reaches critical mass after she moves in with Tracy. Perhaps only a 13-year-old like Reed could have found the exact note in dialogue where the mother tries to get answers and information and is rejected and ignored like an unsolicited telephone call. You might doubt that a girl could conceal from her mother the fact that she has had her tongue and navel pierced, but this movie convinced me of that, and a lot more.

There are moments when you want to cringe at the danger these girls are in. They slip through the bedroom window and hang out on Hollywood Boulevard, they experiment sexually with kids older and tougher than they are, they all but rape “Luke the lifeguard boy” (Kip Pardue), a neighbor who accuses them, accurately, of being jail bait. They want to fly close to danger without getting hurt, and we wait for them to learn how hard and cruel the world can be.

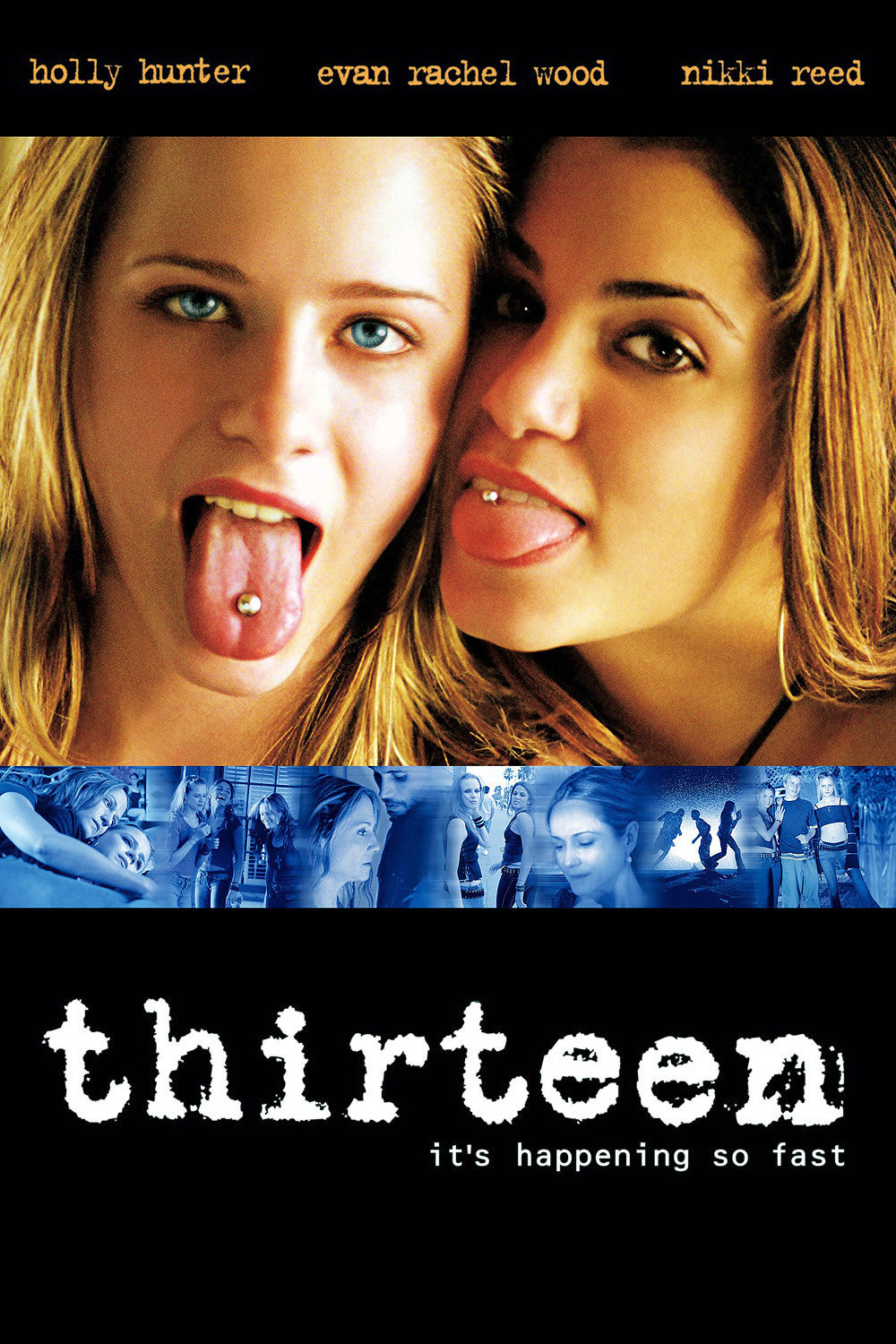

When I meet Reed at Sundance she was with the film’s director, Catherine Hardwicke, who told one of those Only in Southern California stories: Hardwicke was dating Reed’s father, Reed was having problems, Hardwicke suggested she keep a journal, she wrote a screenplay instead, Hardwicke collaborated on a final draft and became the director. Of Reed it can only be said that, like Diane Lane at a similar age, she has the gifts to do almost anything. Although this is Hardwicke’s directing debut, she has many important credits as a production designer (“Tombstone,” “Three Kings,” “Vanilla Sky“) and the movie is smoothly professional, especially in the way it choreographs the comings and goings in Holly Hunter’s chaotic household. Hunter gave a famous performance in “Broadcast News” (1987) as a hyperactive news producer who was forever trying to keep all her plates spinning; her problems here are similar. We know exactly how she feels as she trips on a loose kitchen tile and starts tearing up “the goddamn $1.50 a square foot floor.” Who is this movie for? Not for most 13-year-olds, that’s for sure. The R rating is richly deserved, no matter how much of a lark the poster promises. Maybe the film is simply for those who admire fine, focused acting and writing; “Thirteen” sets a technical problem that seems insoluble, and meets it brilliantly, finding convincing performances from its teenage stars. showing a parent who is clueless but not uncaring, and a world outside that bedroom window that has big bad wolves, and worse.

Note: Watching ‘Thirteen,” I remembered another movie with the same title. David D. Williams’ “Thirteen” (1997) tells the story of a 13-year-old African-American girl named Nina, who runs away from home and causes much concern for her mother, neighbors and the police before turning up again. This movie is set in a more innocent place, a small Virginia town, and has a heroine who has not grown up too fast but is still partly a child, as she should be. The film, which I showed at my Overlooked Film Festival, is apparently not available on video; it would be a comfort after this one.