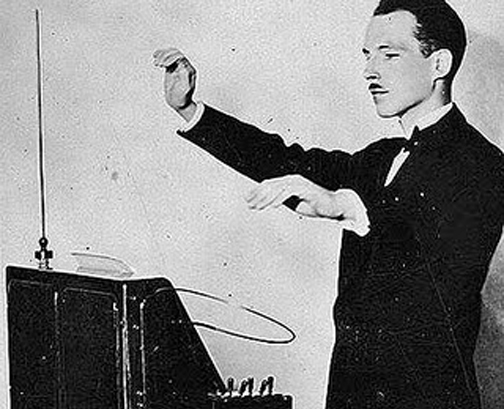

The scientist, whose name was Leon Theremin, was not mad. A professor, he immigrated to America, where by the late 1920s, he had perfected the instrument, named the Theremin. In the next few years, it was featured in concerts at Carnegie Hall and around the country, and employed by an orchestra conducted by Leopold Stowkowski. The concerts were reviewed on the front page of the New York Times, and the instrument was seen as the forerunner of something that was not yet known as electronic music.

Then, in the late 1930s, the scientist mysteriously disappeared from his New York town house. His instrument lived on, in a strange shadow existence; a few people, here and there, remembered it. Its otherworldly sound was used by Hitchcock to suggest mental illness in “Spellbound” by the composer Bernard Herrmann, to accompany alien life forms in “The Day the Earth Stood Still,” by Billy Wilder to suggest alcoholic disorientation in “The Lost Weekend” and by Jerry Lewis to suggest looniness in “The Delicate Delinquent.”

A man named Robert Moog read about the Theremin in hobby magazines, and built and performed on them in high school. He went on to invent the Moog synthesizer, which established electronic music as a reality, and he credited the Theremin as the beginning of his work.

Many musicians used Moog’s devices and, working backward, adopted the Theremin; it can be heard in “Switched-On Bach” series, and on recordings by the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, the Grateful Dead and the Beach Boys (where it provides the vibrations in “Good Vibrations”).

Clara Rockmore, a beautiful New York woman known as “The Virtuoso of the Theremin,” was 18 when she became the professor’s protege.

Others followed him as well, including a ballerina named Lavina Williams, whom he married. None of them ever heard of him again after his disappearance; indeed, they could only surmise that he was still alive.

A man named Steven M. Martin, who had always been interested in Theremins, decided to make a documentary about the instrument. He interviewed Rockmore, Moog and many of the musicians. He found old documentary footage of Theremin himself – including home movies at a birthday party for Miss Rockmore, for which the professor had invented a mechanical cake that lit up when she approached it. From the look in their eyes in one shot from that film, it is clear that they were in love.

And then — then — one day, while investigating the possible fate of Leon Theremin in Russia, Martin discovered that the professor was still alive, at 95! He had been kidnapped in the 1930s by Soviet agents. Martin flew him back to New York for the first time in 60 years. And he was reunited with Clara Rockmore, and they toured Manhattan together, and she played the Theremin once again for him, and their eyes sparkled as they had all those decades ago.

And all of that is true, and all of that is why documentary films have a quality that fiction can envy but never really capture. No novelist could have gotten away with such a story – especially not the parts in the Soviet Union, where Theremin (he is a little hazy and confused about those years) was essentially a prisoner of the KGB, working on electronic spy bugs, and was awarded the Stalin Medal in one year while being exiled in another. His old life in Manhattan, his triumph at Carnegie Hall – all had faded until they seemed like someone else’s memories. His wife had died never learning his fate.

Is the Theremin a serious musical instrument? I think not. It is an instrument like the inventions of Harry Partch, useful for evoking a sound that no other instrument can duplicate, essential when that sound is required, but unnecessary to the musical mainstream. Still, Robert Moog says that it provided the “cornerstone” of modern electronic musical instruments that are serious and essential.

Watching “Theremin: An Electronic Odyssey” is a curious experience. You begin with interest, and then you pass through the stages of curiosity, fascination and disbelief, until in the last 20 minutes, you arrive at a state of dumbfounded wonder. It is the kind of movie that requires a musical score only the Theremin possibly could supply.