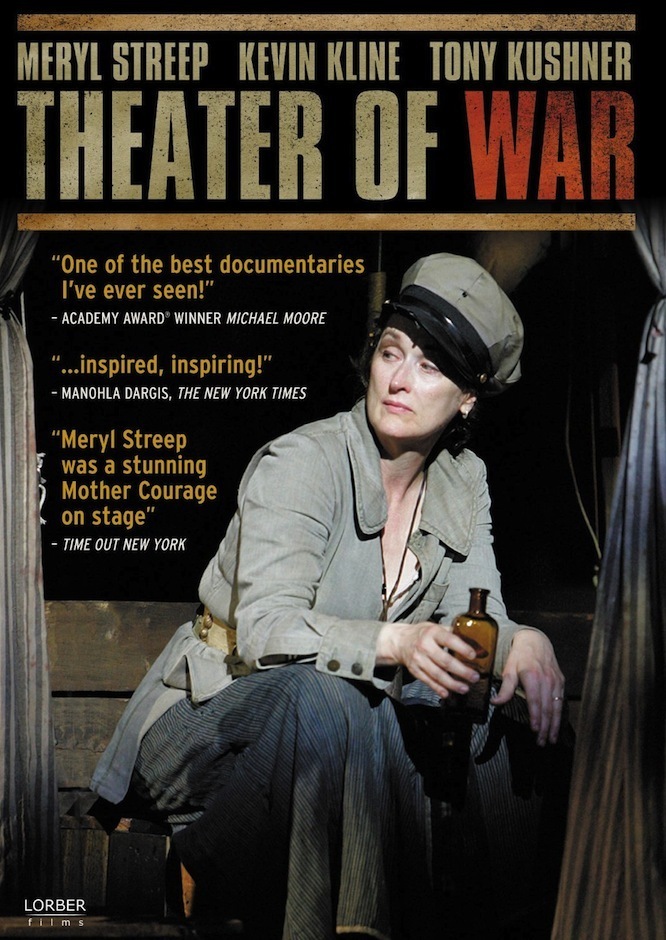

Meryl Streep strikes me as one of the nicest people you’d ever want to meet. Also one of the great actresses, but her down-to-earth quality is what struck me in “Theater of War,” a documentary about the Public Theater’s 2006 production of Bertolt Brecht’s “Mother Courage and Her Children” in Central Park. She rehearses, she works with the composer, she never raises her voice, she endures full-dress rehearsals during a heat wave. The only complaint she has is that it’s not a good idea for audiences to see a performance in “process,” because the work looks like “bad acting.”

“Theater of War,” directed by John Walter, does however have access to all the rehearsals, and intercuts them with documentary material about Brecht, his theatrical career, his life in exile and his adventures with the House Un-American Activities Committee. There are also interviews with Streep; translator Tony Kushner; Brecht’s daughter, Barbara Brecht-Schall, and the veteran theater director George C. Wolfe, a friend of Brecht’s, who witnessed the historic 1949 production in East Berlin.

All of this makes an interesting, if not gripping, film about the play, the playwright and the lead-up work to a stage production. It also leaves me wanting a great deal more. Perhaps in an attempt to emulate Brecht’s anti-war theme, Walter devotes too much screen time to footage of anti-war protests during Vietnam, the Israeli invasion of Lebanon and the war in Iraq. TV news footage means little, and still less that it is sometimes seen integrated into graphics representing 1950s all-American families. Nor do we need to see again that familiar footage of U.S. schoolchildren practicing “duck and cover” in case of a nuclear attack.

Walter is trying to make an anti-war doc on top of his primary subject. Not needed, not effective. There could be more of Streep actually changing a stage moment in rehearsal. More from her co-star Kevin Kline. Another co-star, Austin Pendleton, appears in many shots but is not even mentioned –and he, I believe, would have talked more openly about process.

The film recounts Brecht’s development as a Marxist playwright who deliberately avoided engaging the audience on a emotional level or encouraging it to identify with his characters. He wanted them to rise above the immediate experience to the level of thought and ideology. We are to realize: “War is bad, and everyone loses!” At this Brecht is so successful that I suspect the play is impossible to make truly involving. It is sort of a passion play of the Left, a work which inspires more piety than enthusiasm.

One peculiar element involves college lectures on Marxism by the novelist Jay Cantor (Death of Che Guevara). If it is explained why he was necessary in “Theater of War,” I missed it. His comments are generalized and not pertinent. But, oddly, his students are always seen with black bars over their eyes, like patrons being arrested in a brothel. Brecht was famous for distancing strategies that prevented audiences from getting so swept up in his stories that they didn’t focus on their messages. Perhaps these distracting and seemingly unnecessary black bars are, dare I say, a Brechtian device?

The doc lacks the usual scene of the company gathered to read their reviews; just as well, because the production was not well-received. Oskar Eustis, artistic director of the Public Theater, has said “Mother Courage and Her Children” is the greatest play of the 20th century. My money’s on “Waiting for Godot.”