When the great French thriller “The Wages of Fear” (1953) was first released in America, it was missing parts of several early scenes — because it was too long, the U.S. distributors said, and because they were anti-American, according to the Parisian critics.

Now that the movie is available for the first time in the original cut of director Henri-Georges Clouzot, it is possible to see that both sides have a point.

The film’s extended suspense sequences deserve a place among the great stretches of cinema. Four desperate men, broke and stranded in a backwater of Latin America, sign up on a suicidal mission to drive two truckloads of nitroglycerin 300 miles down a hazardous road. They could be blown to pieces at any instant, and in the film’s most famous scene Clouzot requires them to turn their trucks around on a rickety, half-finished timber platform high above a mountain gorge.

Their journey also requires them to use some of the nitroglycerin to blow up a massive boulder in the road, and at the end, after a pipeline ruptures, a truck has to pass through a pool of oil that seems to tar them with the ignominy of their task. For these are not heroes, Clouzot seems to argue, but men who have valued themselves at the $2,000 a head that the oil company will pay them if they get the nitro to the wellhead where it is needed.

The company, which significantly has the same initials as Standard Oil, is an American firm that exploits workers in the unnamed nation where the film is set. The screenplay is specific about the motives of the American boss who hires the truck drivers: “They don’t belong to a union, and they don’t have any relatives, so if anything happens, no one will come around causing trouble.” There are other moments when the Yankee capitalists are made out as the villains, and reportedly these were among the scenes that were trimmed before the film opened in this country.

The irony is that the trims have been restored at a time when they have lost much of their relevance, revealing that the movie works better as a thriller than as a political tract, anyway. The opening sequence, set in the dismal village where unemployed men fight for jobs, is similar to the opening of John Huston’s “The Treasure of the Sierra Madre” (1948), even down to the detail of visiting the local barber. But while Huston used his opening to establish his characters and work in some wry humor, Clouzot creates mostly aimless ennui.

Although eager to establish his anti-American subtext, he reveals himself as a reactionary in sexual politics with the inexplicable character of Linda (Vera Clouzot), who does menial jobs in the saloon. She is in love with one of the local layabouts (Yves Montand, in his first dramatic role), who slaps her around and tells her to get lost, and she spends most of her time sprawled on the ground, although always impeccably made up. There is no apparent purpose for this character, apart from the way she functions to set up such lines as, “Women are no good.” If the opening sequences, now restored, have a tendency to drag, the movie is heart-stopping once the two trucks begin their torturous 300-mile journey to a blazing oil well. The cinematographer, Armand Thirard, pins each team of men into its claustrophobic truck cab, where every jolt and bump in the road causes them to wince, waiting for a death that, if it comes, will happen so suddenly they will never know it.

Clouzot does an especially effective job of setting up the best sequence, where first one and then the other truck has to back up on the unstable wooden platform in order to get around a hairpin bend in the trail. The first truck is used to establish the situation, so we know exactly what Montand is up against when he arrives at the scene: Rotten timbers break, the truck begins to slide sideways, a steel support cable gets caught on the side of the truck, and we are watching great technical work as it creates great fiction.

When William Friedkin remade “The Wages of Fear” as “Sorcerer” in 1977, he combined this scene with a later one, in a jungle setting, to create a sequence where a truck wavers on a vast, unstable suspension bridge. Friedkin had greater technical resources, and his sequence looks more impressive, but Clouzot’s editing selects each moment so correctly that you can see where Friedkin, and a lot of other directors, got their inspiration.

One thing that establishes “The Wages of Fear” as a film from the early 1950s, and not from today, is its attitude toward happy endings. Modern Hollywood thrillers cannot end in tragedy for its heroes, because the studios won’t allow it. “The Wages of Fear” is completely free to let anything happen to any of its characters, and if all four are not dead when the nitro reaches the blazing oil well, it may be because Clouzot is even more deeply ironic than we expect. The last scene, where a homebound truck is intercut with a celebration while a Strauss waltz plays on the radio, is a reminder of how much Hollywood has traded away by insisting on the childishness of the obligatory happy ending.

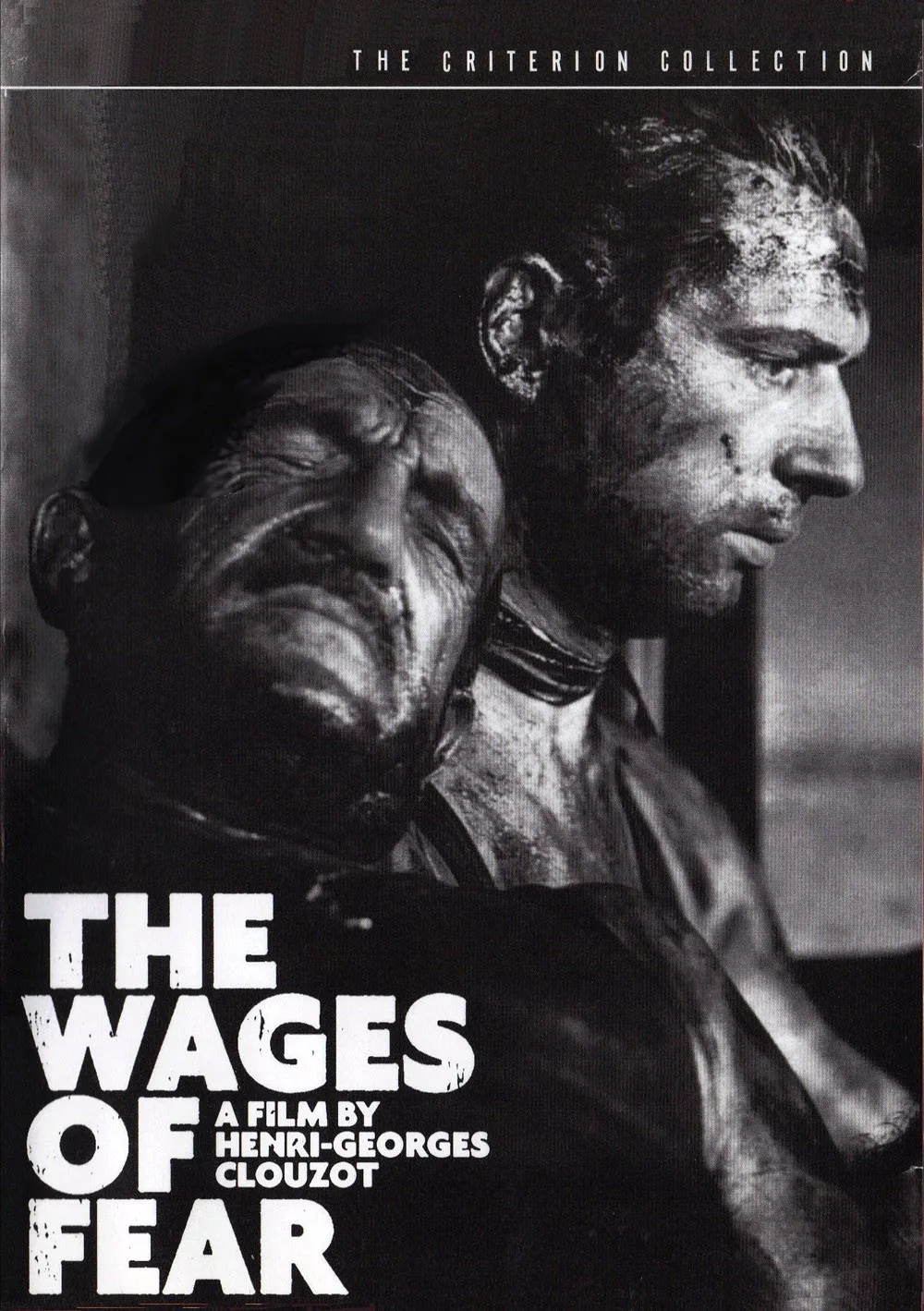

NOTE: This new, restored print of “The Wages of Fear” is now at the Music Box, and is also available on videotape and on a laserdisc in the Criterion Collection. See it on the big screen if you possibly can.