The happy ending, like all clichés, is hard to define. I used to believe all happy endings resemble one another, while every unhappy ending is unhappy in its own fashion. But that will not do.

On the basis of two current films, the splendid “The Two of Us” and the so-so “With Six You Get Eggroll,” I’ve decided there are at least two kinds of happy endings: the mechanistic and the organic.

The mechanistic happy ending is simply the regular Hollywood ending we know and love. It bears little relationship to what has gone before. Doris Day may just have dumped Brian Keith in the middle of the street in his underpants, but he will somewhere borrow a Good Humor uniform and they’ll be together again, in love again, all misunderstandings cleared up.

This sort of ending is simply a mechanical arrangement of characters, designed to reassure us.

The organic happy ending, on the other hand, grows out of the film. It is not only a happy ending but a logical one. The movie ends well because the characters recognize their problems and solve them. We feel good.

And that is the test, I think. The conventional Hollywood ending satisfies some sort of cheap, shallow desire to have the movie turn out all right. But the other kind fills us with a glow of happiness.

“The Two of Us” is such a movie, and has such an ending.

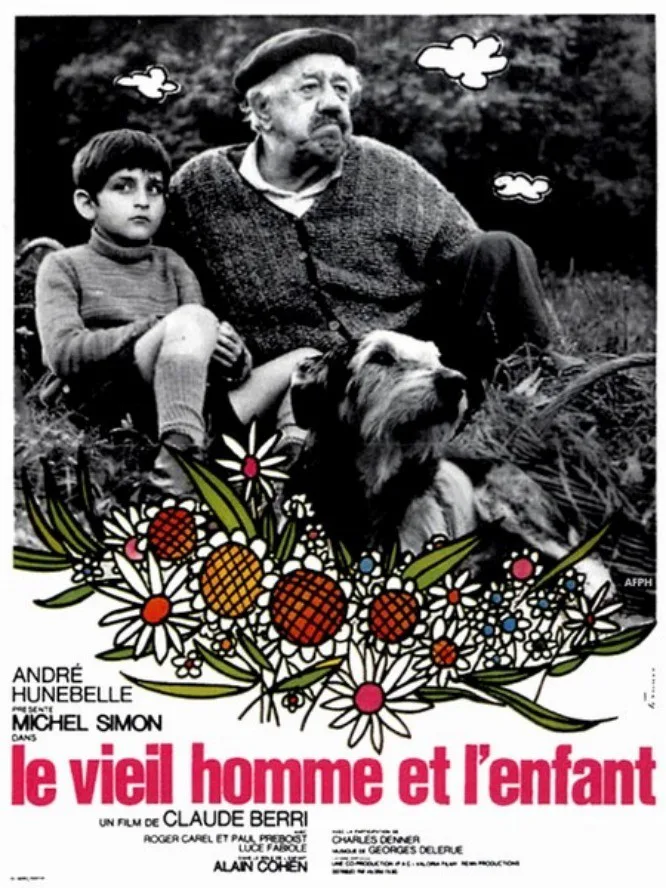

The story is about two people: an old man, and a boy. The old man (Michel Simon) lives in the French countryside on a farm with his wife, dog, son, daughter-in-law and anti-Semitic prejudices.

The boy (Alain Cohen) is Jewish, and in 1944 his parents send him to the country at the time of the Nazi occupation. His identity must be kept a secret. His parents give him a resounding Christian name, teach him the Lord’s Prayer and send him away with their fingers crossed.

What follows is a series of adventures, some small, some large, involving the old man, the boy and human prejudice. The old man blames the war on a secret agreement among the Jews, the English, the Freemasons, Winston Churchill and any other group that happens to occur to him. He listens to the nightly propaganda broadcasts with fervor, and solemnly assures the boy that Jews have big noses and eat by candlelight.

The trouble is, the old man’s nose is bigger than the boy’s. Some other things don’t fit either. The boy is worried at first that his identity will be discovered, but he relaxes and begins to humor the old man. For it has become quite clear that the old man, like all of us has more prejudices than available targets.

A great affection grows up between them, in a series of beautifully acted scenes. There is pure comedy, a great deal of gentle satire and a scene of tragedy: The boy’s head is shaved at school. The old man comforts him, and their friendship is cemented.

The ending is happy, but it isn’t phony. If Hollywood had done this film, the old man would have discovered at the end that the boy was Jewish. Then there would have been a fine liberal curtain speech about the brotherhood of man.

But Claude Berri, who wrote and directed “The Two of Us,” doesn’t fall into that trap. The old man never finds out and, what’s more, doesn’t need to.