Polish journalist Ryszard Kapuściński wrote, in regards to the momentous events taking place throughout Eastern Europe in the spring of 1989:

“Germans say Zeitgeist, the spirit of the times. It is a fascinating moment, fraught with promise, when this spirit of the times, dozing pitifully and apathetically, like a huge wet bird on a branch, suddenly and without a clear reason (or at any rate without a reason allowing of an entirely rational explanation), unexpectedly takes off in bold and joyful flight. We all hear the shush of this flight. It stirs our imagination and gives us energy: we begin to act.“

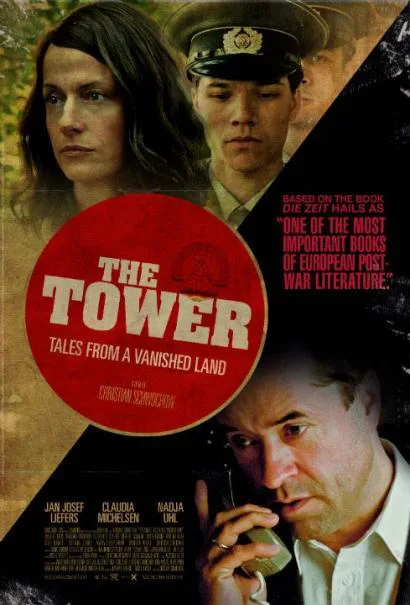

Set in East Germany during the final decade of Communism, Christian Schwochow’s “The Tower,” a German mini-series based on the best-selling novel by Uwe Tellkamp, is about the lead-up to such a moment of collective flight. The film ends with the image of a huge flock of birds erupting up into the sky, wheeling through the free and empty air. When the end came for the GDR, it came with a whimper, in the form of a radio broadcast with an official voice announcing to the populace that there would no longer be any restrictions on border crossings. You’re free to go, basically, was the message. What started as a trickle of refugees became a vast flood. “The Tower” is beautiful to look at, elegantly filmed, with very good performances across the board. There are multiple story-lines (too many, really) and a big cast of intersecting characters (its literary source-material is evident in the adaptation). At its best, “The Tower” shows what life felt like to those who lived at that singular time, to those who dozed “pitifully and apathetically” in an unchanging political system before the rules changed, seemingly overnight.

Richard Hoffman (Jan Josef Liefers) is a surgeon at a clinic in Dresden, with burn tissue all over his back, an eternal reminder of the 1945 firebombing of his hometown when he was a child. He is married to a nurse (Claudia Michelsen), and they have a teenage son named Christian (Sebastian Urzendowsky). Richard has been carrying on an affair with his secretary that has resulted in a child, now 5 years old. Hoffman goes back and forth between the two homes, and his wife supposedly knows nothing about the second family, although you can see her give him a couple of sharp glances on occasion. The mistress wants Hoffman to get a divorce. Hoffman, due to professional and personal reasons, knows that is impossible. In the meantime, he is on autopilot with his own duplicity.

The forms of Communist rule are still in place, and yet are greeted with eye-rolls by nearly everyone. The forms have become empty, symbols one must kow-tow to, but are ultimately meaningless. It is a world dominated by propaganda and censorship, where “thoughtcrimes” (to quote Orwell, as the characters in “The Tower” often do) are punishable offenses, where the Stasi are still a terrorizing force. Socialism, ironically, created a strict caste system (one privileged person jokes, “No privileges. Wasn’t that the message once?”), and the Hoffman family in “The Tower” would be considered “bourgeois”; a pampered elite group, doctors and book-publishers and musicians. Their private lives are as chaotic as their public lives are appropriate. In such a political system, lying is a necessary skill.

We meet other characters in the Hoffman social circle, including Meno (Götz Schubert), a book publisher who works with authors on removing potentially problematic passages in their novels. He loves literature, and he has been forced to become a censor. It is despicable work and exacts a psychological toll on Meno (Schubert is phenomenal in the role) especially when he is assigned to work with an author (Valery Tscheplanowa) who refuses to edit her novel about the Red Army’s rape of German women upon invading the country. “It happened,” she says. The publisher’s reply comes back: “The question is what good does it do to write about it.” She is thrown out of the Writer’s Union because of her refusal, placing her beyond the pale, in exile in her own country, all publishing doors closed to her. Meno is haunted by her, keeps trying to reach out, right that wrong.

There are colleagues of Hoffman’s at the clinic, one of whom collects vintage cars, but who also is secretly building an airplane in his garage to take his wife and daughter across the border. Hoffman’s mistress, played by Nadja Uhl (so excellent in “The Baeder Meinhof Complex,” and excellent here too), is desperate for her lover’s protection and attention, and becomes a liability when he turns his back on her and their daughter. These are private matters, and yet they get the attention of the Stasi, who can use it to blackmail Hoffman.

Schwochow keeps these plot-lines moving smoothly and briskly, filming it all in a cold green-tinted palette, suggesting the deprivations and stagnancy of the world behind the Iron Curtain. There are no primary colors. This is a landscape underwater. The film is strongest when it shows the direct connection between State control and private life. This is most clearly shown in Meno’s relationship with the censored author, and in Christian’s increasing trouble with authority. Christian’s schoolwork is propaganda, and school papers are graded according to whether or not they express the proper “class attitudes.” Christian starts getting in trouble for reading non-approved books, and his parents flip out. He was raised in an intellectual household, and yet in public he is meant to toe the party line. His parents encourage him to live the same duplicitous life that they do, and he stops being able to comply. The transformation of Christian from a gawky sweet teenager to tough-minded grim veteran of multiple authoritative organizations (school, military, prison) is heartbreaking.

“The Tower” loses focus with some of the characters, becoming generic, a soap opera we’ve seen before. Hoffman’s situation with his secret mistress and his wife could happen in any country, any time, and the film slackens in these sequences. When the story goes back to Meno and Chrsitian, it tightens up again, finding its underlying architecture, the themes that are the film’s engine. Yes, there is danger in Hoffman’s personal situation, but it’s personal, and the danger is not as palpable as the danger Meno faces when he tries to smuggle the author’s banned manuscript out of the country to more welcoming publishers in the West. Meno goes from a laughing, confident man to a ruined shell of an individual, and it drives the tragic point home about what politics have done to talented minds like Meno’s.

Schwochow, who grew up in East Germany, has a wonderful subtle touch in portraying the small details of everyday life. Meno and Christian sit in an empty field in the middle of nowhere, watching television in the one spot where they can pick up the signals from the TV tower in West Germany. It’s like messages arriving from a distant planet. In one scene, Hoffman and his wife take a walk through the streets of Dresden at night, and the power goes out (a common occurrence). Neighbors call out to one another, joking about “the reality of socialism”, and then someone puts a record on an old crank-up victrola, scratchy music floating out of the house. Hoffman and his wife dance slowly in the street, holding on to one another. It’s a beautiful scene, containing all the complexity and irony and challenges of the political and personal moment. In one of the dinner party scenes at the Hoffman house, everyone shares about how difficult it is to praise Socialism at public events. One woman says she “thinks of something beautiful” when she has to say the word “Socialism” and so they go around the table, jokingly listing movie stars they will think about the next time they have to say the word. “Brigitte Bardot.” “Brooke Shields.” “Alain Delon.” “The Tower” is full of such darkly humorous and intelligently observed moments.

As the film veers into 1988, the scenes get shorter, the pace more relentless, hopping from one person’s arc to the next and then back, Schwochow giving a palpable sense that time, after having been stopped for almost half a century, is speeding up. The final half-hour of the film is thrilling, individuals confronting the crack-up of the State in their own individual ways; the groundswell of freedom and liberty destabilizing the entire atmosphere. Characters look at one another with an open sense of awe and fear in their faces, as if to say: “Is this really happening? Is this real?”

“The Tower” is too long, and could do with some serious trimming, but in general it is a powerful and engrossing look at the moment in history when the tide started turning; when the people reared up out of their apathy; when the “spirit of the times” became an irresistible flood.