Of course you go to River Phoenix‘s last finished film in a certain state of mind. You remember his clarity and power in films like “Running on Empty” and “Dogfight,” and against those images you hold the shots of his dead body on the sidewalk outside the Viper Club. His death still seems all wrong. How could he have been so careless of his responsibility to his own future? These thoughts are there as Peter Bogdanovich’s “The Thing Called Love” begins, but there are more pragmatic thoughts, too: Will his performance reveal signs of the drug use that ended his life? Or will this farewell performance show him at the top of his form? The film is about four young singersongwriters who arrive in Nashville hoping to be discovered. They all gravitate to the Bluebell Cafe, which features new acts on weekend nights, and where a lot of stars have gotten their starts. Maybe, these kids dream, lightning will strike again.

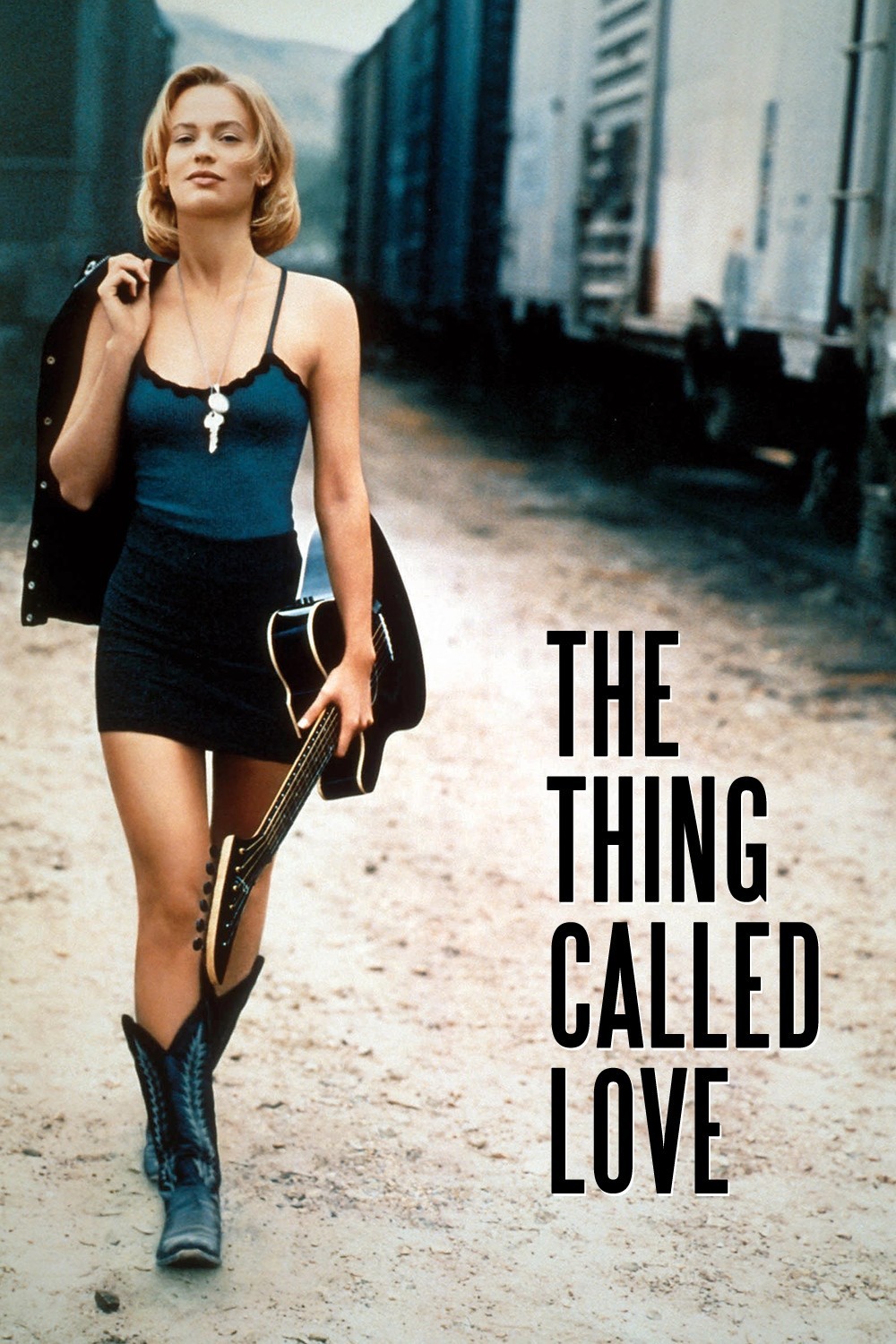

The movie stars Samantha Mathis as Miranda Presley (“That’s my real name, and I’m no relation!”). At first, she is naive and not very talented, but she has a sweetness about her that impresses Lucy, the veteran owner of the Bluebell, played by country singer K. T.

Oslin. “If I don’t read your name,” Lucy always says at the end of the weekly auditions, “that just means I don’t think you’re ready yet.” Among the other young singers hoping to be discovered are Kyle (Dermot Mulroney), a would-be cowboy from Connecticut; Linda Lue (Sandra Bullock) from Alabama, and James Wright, the River Phoenix character, who comes from Texas and obviously has the most talent of the crowd.

In Phoenix’s first scene, it is obvious he’s in trouble. The rest of the movie only confirms it, making “The Thing Called Love” a painful experience for anyone who remembers him in good health. He looks ill – thin, sallow, listless. His eyes are directed mostly at the ground. He cannot meet the camera, or the eyes of the other actors. It is sometimes difficult to understand his dialogue. Even worse, there is no energy in the dialogue, no conviction that he cares about what he is saying.

Some small part of this performance may possibly have been inspired by Phoenix’s desire to emulate James Dean or the young Brando in their slouchy, mumbly acting styles. And maybe that’s how Bogdanovich and his associates reassured themselves as they saw this performance taking shape. After all, Phoenix came to the project as one of the most promising actors of his generation, and perhaps somehow an inner magic would transmit itself to the film.

It does not. The world was shocked when Phoenix overdosed, but the people working on this film should not have been. It is notoriously difficult to get addicts to stop their behavior before they have found their personal bottoms, and so perhaps no one could have saved Phoenix, who was not lucky enough to find a higher bottom than death. But this performance in this movie should have been seen by someone as a cry for help.

Bogdanovich does what he can. Samantha Mathis is plucky and spirited in the lead role, and the milieu is entertaining (everyone in the movie, even cops and taxi drivers, seem to be aspiring songwriters). But at the center of the film is an actor whose mind and heart are far, far away, and he is like a black hole, consuming light and energy. He’s running on empty. Sometimes there are even scenes where you can sense the other actors scrutinizing Phoenix in a certain way, or urging him, with their tones of voice, to an energy level he cannot match. It is all very sad.