“The Summer Book” is a haiku of a movie, conveying profound thoughts about time, memory, loss, and nature through a simplified, meditative, cinematic language of exquisite images and gentle music. Most of the film is just three characters in one setting, an isolated island in the Finnish archipelago. It is based on the 1972 book of the same title by Finnish author Tove Jansson, inspired by her own family, a series of brief vignettes about three generations over the course of one summer. Jansson is best known for her books about the nature-loving Moomin creatures, favorites of both producer and star Glenn Close and director Charlie McDowell.

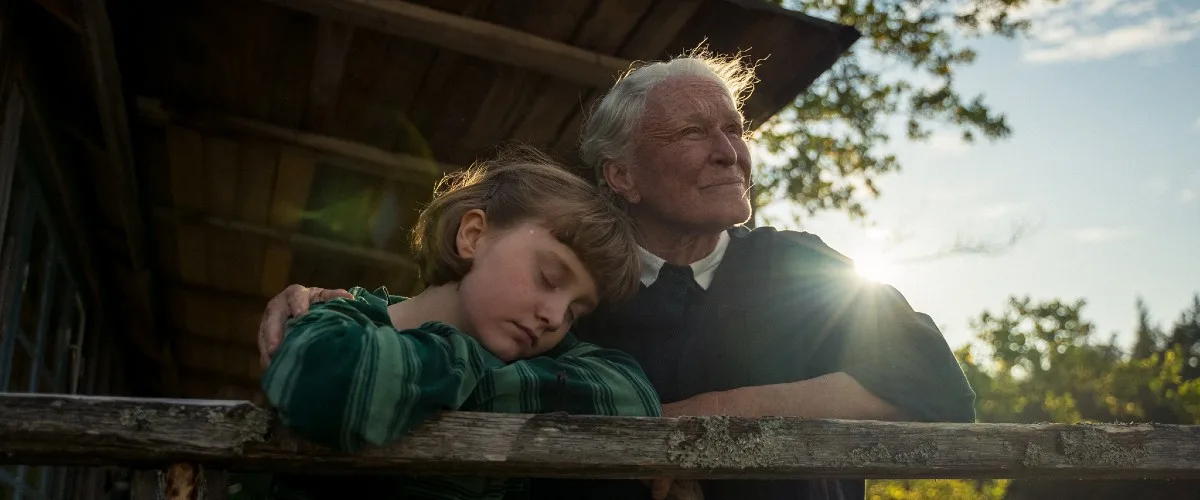

Close plays the grandmother, with tightly braided, iron-colored hair, walking heavily with a cane. She is observant, opinionated, but affectionate, and devoted to her young granddaughter, Sophia (a lovely, wonderfully natural debut from then seven-year-old Emily Matthews). Their moments together are the heart of the film. The third member of the family is just billed as Father (Anders Danielsen Lie), Sophia’s dad, Grandmother’s son, and, like Jansson, an artist and illustrator.

As the movie begins, the trio arrives at the island in a small boat, and we see from their easy familiarity with the cabin that it is an annual family retreat. As Father walks through the door, he sees a straw hat on the coatrack, and Grandmother sees him see it. She quietly takes it from him and says, “I’ll find somewhere.” Sophia does not notice, but it tells us that the wearer of that hat is gone, and Father is grieving. He and Sophia have a relationship of easy comfort when he has time for her, and they laugh together when she tosses seaweed at him. But he is distant, and at one point she tells Grandmother, “He doesn’t love me since she died.” Later, Grandmother admonishes him to try harder.

The rest of the film is less direct, more elliptical, poetic, and meditative, with breathtaking images of sunrises and (very late in the evening at that latitude) sunsets, waves, sunlight dappling the water, and vegetation, including a poplar Father plants because it was his wife’s favorite. The absence of any technology other than a failing outboard motor on the boat gives the story a timelessness, as though it always was and always will be untouched by the world or even by time itself. Over the closing credits, you can see the real-life Jansson, her hair decorated with Midsummer flowers like Sophia and Grandmother in the movie, on the island that inspired the story.

An older man stops by to drop off fireworks for the Midsummer celebration, and later, the family wonders if he will return to see them set off. Father does not think so. “The stink of grief keeps him away.” Sophia and Grandmother explore in a boat, defying another island’s “No Trespassing” sign because, Grandmother explains, a polite person would never intrude without an invitation, but a sign like that is “a provocation.” That island’s family arrives and welcomes them warmly, earning Grandmother’s respect with their care for the environment. Sophia is horrified when they accidentally cut a worm in half, but Grandmother reassures her it will be two worms now.

Glenn Close, who had three hours of prosthetics to age her and slept in the house on the island while filming, gives one of the best performances of her career, conveying everything about the character with her eyes, her determined hobble over the rough terrain, pulling the hairpins from her braids, the touch of her hand on Sophia’s hair and then, near the end, on Father’s. It takes endless talent and experience as an actor to form a performance around a child, adapting every response, movement, and speech to make them appear completely natural. The perspectives of the older woman trying to hold on to her memories and be present for her family and the child who dictates a story and then asked if she wants to hear it read back, says blithely, “Save it for my grandchildren,” evoke our own experiences of long summer days. These years go by too fast, and we never have enough time with the people we love.