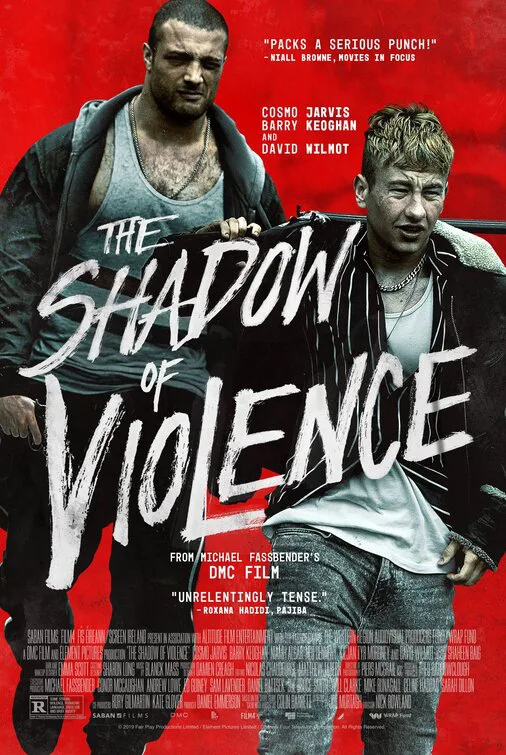

The celebrated Dom Toretto cross-stitch aphorism goes: “I don’t have friends. I got family.” Nick Rowland‘s “The Shadow of Violence,” which concerns an Irish Toretto-type afraid of his own muscles, expands the ideology: “The Devers don’t care about blood. They say it only makes you related. It was loyalty … loyalty made you part of the family.”

Cosmo Jarvis’ hulking and very sad Douglas exemplifies this sense of loyalty with the Devers, a clan of freaky bloodsucking mobsters who seem to be the reason why it’s so cloudy in their spacious corner of Ireland. Douglas is not of Dever blood; he has his own toxicity that made him a self-proclaimed violent child, and later a boxer. He was taken in by the brash hooligan Dympna (Barry Keoghan) and his two drug dealing uncles after a boxing match when he accidentally killed someone—a traumatic event for Douglas that also put him on the market as a heavy, whether his broken heart is in the work or not.

After we see an extreme close-up of Douglas’ clenched fist, his exhausted voiceover relaying the above thoughts on family and his own history of violence (“It’s just a way a fella makes sense of his world”), Douglas is sent on his latest gig: beat the ever-loving crap out of an old guy named Fannigan (Liam Carney) who sexually assaulted Charlotte, one of the teenage women in the Dever family, the night before. The scene is impressively staged by debut director Nick Rowland, as the camera goes wide to show Douglas toss Fannigan’s whole body through a glass coffee table, while a yellow light in the background cuts a silhouette. However stagey it is, it recalls the beautiful violence in the movies of Nicolas Winding Refn, who certainly has his own roster of moody muscle men. This scene proves to be a highpoint for a character study that gradually loses its ability to say something interesting about such toxic aggression, aside from watching Jarvis’ sorrowful performance.

A semblance of peace for Douglas comes from the time he squeezes in with his son Jack (Kiljan Tyr Moroney), and the boy’s mother, Ursula (Niamh Algar), who has a softness for the gentle giant Douglas can be, but has clearly set a boundary with him. When Douglas is not bounding around with the more outwardly aggressive but physically smaller Dympna, he’s trying to spend time with this son that he’s progressively losing touch with, especially as Jack might be going to school far away in Cork. But violence always lingers, as when Douglas has to cut time with Jack on the playground short, and take him with to meet Dympna’s uncle Hector (David Wilmot). The order comes in—simply beating up Fannigan was a mistake. Fannigan needs to die, or else. Dympna tries to hype Douglas up to commit murder in the following scenes, but the order leaves a big lump in Douglas’ throat, so much that when he’s about to finally throw Fannigan through death’s door, he lets him go. That’s where “The Shadow of Violence” truly begins, turning on a decision that doesn’t enhance the story as much as one might hope.

This is the tale of a man’s soul being fought for, and one of the few compelling things about it is that the man in danger is the bulkiest guy in the room. The more time Douglas spends with Barry Keoghan’s charismatic and slimy character, it becomes apparent of the influence that Dympna has over Douglas simply because of his two uncles, and the control that in turn gives Dympna. Later on, there’s a car chase scene with one of the two uncles, but because the uncle has a gun and even more a sense of actually being able to kill, it is frightening to Douglas. Along with the extremities implied for a singular murder request, it’s a refreshing perspective—especially for fellow height-inclined people who sometimes feel a foot shorter than they are—but it hedges the story toward the obvious confrontations of a man’s interior clashing with the demands of his exterior, and the lack of communication he has to wrangle the two. Rowland made a short film in 2014, “Slap,” about a boxer who struggles with his happiness in wearing makeup and dresses, and this feature-length exploration of such turmoil seems less fleshed-out in comparison.

Despite the story not having much to say about Douglas besides his tragedy, Jarvis makes you feel for his tumultuous existence. He’s going for the meaningful weariness of a young Sylvester Stallone and he gets it—it’s one of the kinds of portrayals of masculinity in which the bulky actor looks ready to burst into tears any second. Especially when he has interactions with people that show just how lonely he is, Jarvis constantly bites his lip as if that’s the last thing keeping him together, and his voice gets rockier as the preceding events pummels Douglas until he can take no more. When Douglas does finally get to that release in a climactic moment, it’s a testament to the full approach that Jarvis takes; even if the script seems enamored with him as more of a concept than anything else, at least the catharsis is big and nuanced, and gripping within long takes. It’s a striking performance, if only to see an actor so in tune with their physical and emotional halves portraying someone who is the exact and tragic opposite.

But while Jarvis puts a memorable mug to the script’s meditations, you have to squint too much to see director Rowland’s signature on this broad idea of machismo, who is working from a script by Joseph Murtagh. They collectively boil down much of the raw stuff, and eventually lead this story to cliche moments of guns being pointed at faces, or hollow scenes of realization for Douglas that drop out the synth-driven score to complete silence and put characters in dramatic slow motion, all to make a dull point. When the extra-gothic Uncle Paudi (Ned Dennehy) speaks in a sinister metaphor about a sick dog that needs to be put down, it’s too obvious that the writerly portion of the story is taking control; the same with Douglas’ voiceover, which can be more convenient in spite of its gruesome wisdom. As much as the film yearns for prestigious humorlessness and austerity in this sullen patch of Ireland—captured with wide shots that indicate rows of white houses isolated in large gulfs of nothingness—the story’s few threads end in familiar places, as if it has to be that way. It doesn’t, and better movies of this gritty ilk have proved that.

The original title for this movie outside of America is “Calm With Horses,” a reference to the adapted short story by Colin Barrett. It almost feels damning to talk too much about how this movie uses horses as a metaphor for the tenderness within Douglas, as happens in a couple scenes where Douglas watches the horses that Jack and his friends are riding, before being coached on how to get on one himself. It’s supposed to be a calming moment but it’s one of the story’s bigger flaws, placing it well in the shadow of previous horse/man character studies like “The Rider” and “The Mustang.” Thankfully, there’s more to this project than horses, and a bit more to it than violence (“The Shadow of Violence” is a goofy American replacement, and yet a better name in comparison). But the film’s poetry is like the close-up of the clenched fist that Rowland uses to introduce us to his character study—there’s a thoughtfulness behind the tight fingers, maybe even a broken soul, but its expression is that of a blunt object.

Now playing in theaters.