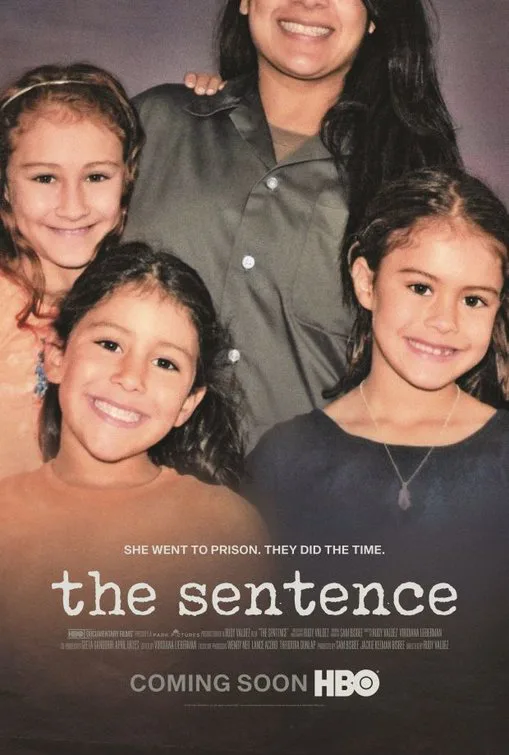

Rudy Valdez‘ sister Cindy was arrested for “conspiracy,” i.e. having knowledge of the crimes of her drug-dealing late boyfriend. She got a 15-year prison sentence, basically serving the time her boyfriend would have served, had he not been murdered. This type of “conspiracy” charge, often resulting in draconian sentences, is so notorious legal experts and members of Congress call it “the girlfriend problem.” Knowledge of a crime brings as heavy a sentence as if you had committed the crime yourself. By the time Cindy was arrested, she had gotten her life together, married a kind man named Adam. The couple had three young daughters. She was still breastfeeding her youngest when she was taken to prison. The family was shattered. Rudy Valdez is a cinematographer and camera operator and “The Sentence”—a documentary portrait of the devastating impact mandatory minimum sentences have had on his family—is his first full-length film. Valdez remarks to the camera, “Standing behind a camera has allowed me to cope.”

The War on Drugs was a many-tentacled monster. A number of laws were passed—1984’s Sentencing Reform Act, plus the “three strikes law”—as part of the campaign to curtail and punish drug dealers. These new laws—along with mandatory minimums for certain offenses—resulted in massive and often massively unfair sentences. It also criminalized drug addiction. Mandatory minimums have been controversial from the jump: they were imposed on the judicial system from the legislative branch, essentially tying judges’ hands. Context or extenuating circumstances could no longer be considered, and so you had the repeated spectacle of a kid barely out of high school serving 15, 20 years for possession of a small amount of crack cocaine. No second chances, no possibility of clemency.

At first, Valdez’s documentation was a way to keep a record of his nieces’ lives for their mother while she was incarcerated. She would be missing their entire childhood. So the footage is mostly of dance recitals, Christmases, phone calls with Mom. As the years pass, these scenes repeat. The oldest child is the only one with clear memories of her mother. Adam does his best to keep things afloat, taking the kids to visit their mother in prison, which became impossible when Cindy was moved to a prison in Florida. Adam and Cindy divorce. The kids get older, Valdez sitting down to interview each of them every year. Cindy and Rudy’s parents are nearly destroyed by what happened (Mr. Valdez, in particular, can barely speak of it without bursting into tears). Cindy, only heard over the phone, tries to put on a brave face for the kids, but time starts to wear her down.

This is all very compelling footage, and there are some truly heartbreaking moments. “Where’s Mommy’s heart?” Cindy’s voice comes over the phone. Her three girls say together, “In my heart.” You can’t fail to connect the dots that mandatory minimums plus “the girlfriend problem” leads to what amounts to a travesty of justice. But there are unanswered questions embedded in the story. It’s not clear what actually happened with Cindy and her boyfriend. We never learn why he was murdered. We don’t hear about the level of her involvement or knowledge. These are pretty essential details, at the very least for providing context.

A couple of legal experts speak in “The Sentence” on the problem with mandatory minimums, but beyond that the outside world doesn’t really exist. Valdez assures Cindy he is trying to get her sentence reduced, but we see none of that process. Many of these laws are still on the books. “The girlfriend problem” remains. It’s impossible to witness the emotions of the children, of Adam, of the Valdez parents, of Cindy, without feeling for them—it’s an emotionally exhausting film—but a little bit of perspective might have resulted in an even more politically urgent document. As it is, though, “The Sentence” is the beginning of a conversation that needs to continue.