“The Selfish Giant” is easy to admire but difficult to recommend, because its vision of friendship, poverty and desperation is so stark. Written and directed by Clio Barnard, this film about adolescent boys who gather scrap to help their families is based on a fable by Oscar Wilde. But where Wilde’s story summons warmly cathartic tears, the tears this film earns are colder and grimmer. Its outcome feels both unfair and inevitable.

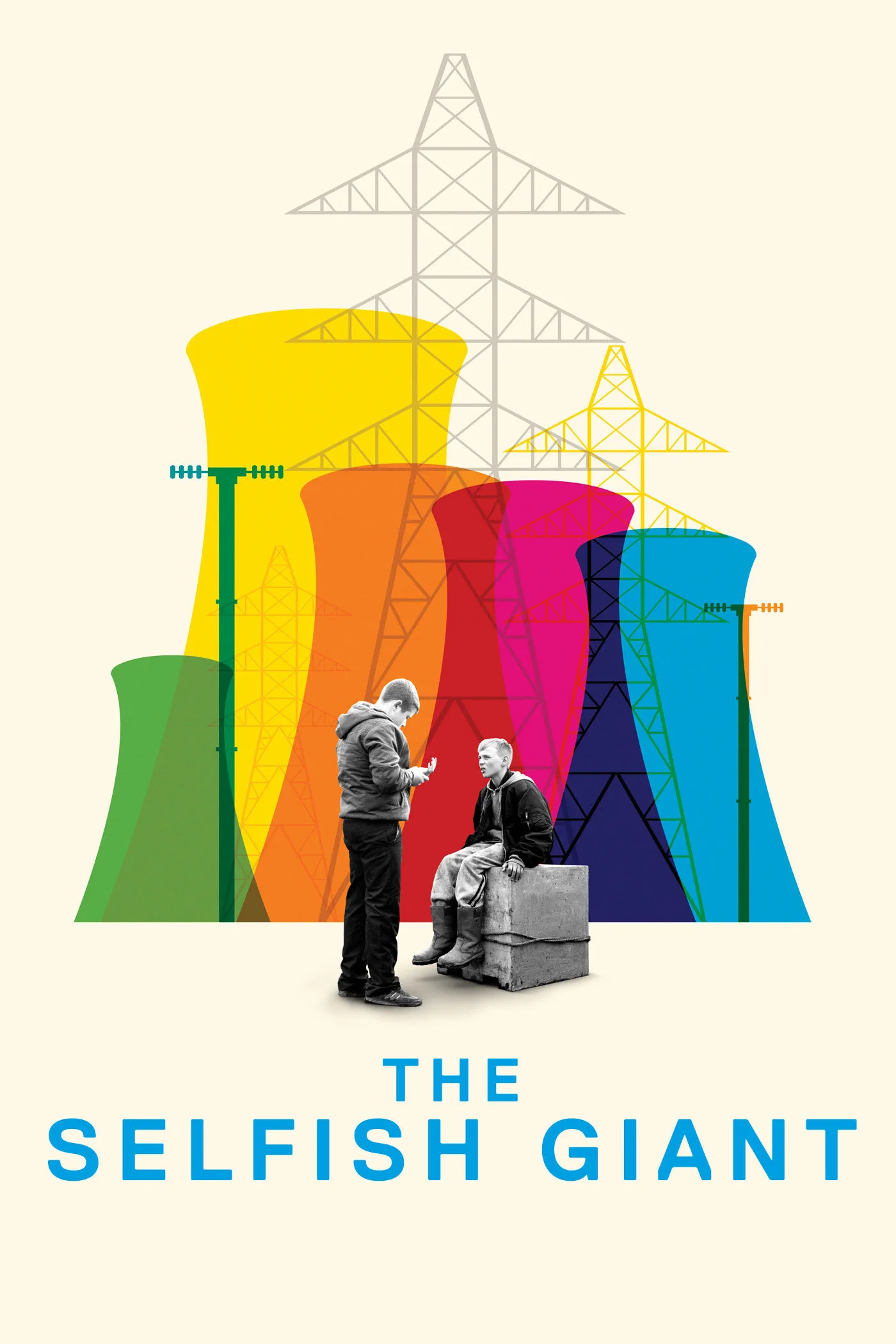

The film is set in West Yorkshire in Northern England, against a backdrop of cooling towers and buzzing transformers. There’s no hint of a healthy economy. This slice of life seems populated mainly by scavengers and people who used to scavenge but gave up. Its heroes are the smallish, blond Arbor (Conner Chapman), who’s hot-tempered and impulsive and seems to have a spectrum disorder, and the taller, kinder, dark-haired Swifty (Shaun Thomas), who often serves as Arbor’s voice of reason. They’re best friends, as close as brothers.

Arbor lives with his exhausted and short-fused single mom (Rebecca Manley) and his drug-addled, volatile older brother (Elliott Tittensor). Swifty’s house is as cramped and rundown as Arbor’s; it’s packed with seven siblings, plus an angry drunk dad (Steve Evets) and a mom (Siobhan Finneran of “Downton Abbey”) who has the haunted look of a prisoner who has accepted that she’ll die behind bars. One of the first scenes set in Swifty’s house ends with Swifty’s dad dragging a fake-leather couch out of the living room and onto the lawn; he plans to sell it to pay the electric bill.

Arbor and Swifty want to improve their lot. They see a glimmer of hope in selling discarded appliances, cookware and wiring to scrapyards. They borrow a broken-down horse from a scrapyard owner to draw a cart around, but the scrapyard owner—the innocuously named Kitten (Sean Gilder)—charges them for the animal, and sometimes skims more at the end, because he can. The boys soon realize there’s more money in copper wiring than in dumpster and curbside garbage. They start collecting wire that was never meant to be collected, growing more brazen with each outing, as if daring fate to crush them.

Kitten encourages Arbor and Swifty to take greater risks for bigger payouts. We’re given to understand that this is typical behavior—that scrapyard owners passively encourage minors to “liberate” other people’s property because they can’t be punished too harshly if the cops catch the kids thieving, or if somebody has an accident. The boys’ industriousness pays off in the short term: their eyes light up when they see wads of cash being pushed through pay windows. But in the long term, it’s a sucker’s game.

Barnard fills out this subculture with a journalist’s eye. The light, the soot, the fog, the way sun hits the sides of buildings, the subtitled slang-riddled dialect, the posturing, the moments of ribald humor and casual bullying, the offhand exploitation of children and horses, all bespeak great powers of observation. Barnard sometimes films the boys in long shot. They’re flyspecks inching along cracked pavement and weed-strewn fields, industrial northlands looming behind them. Even when these images are used for rhythmic purposes—to give the eye a chance to breathe between bouts of close-up camerawork—they’re never purely pictorial; they’re putting the boys and their story in a larger context.

A low-speed chase between rickety horse carts has a nerve-wracking physicality. In a time of CGI-driven filmmaking, even the most epic action has little dramatic or figurative weight. This is, no matter what safety precautions were taken, an actual event. You worry about the horses and riders who are being followed by a carloads of drunken spectators and bettors, a soused peanut gallery on wheels.

The filmmaker shows how the metal is collected and haggled over, and the personal and economic factors that affect scrappers’ and buyers’ survival. The viewer may be reminded of the borderline-slave economies of the early 20th century American economy, before the unions settled in. Just as a 1920s miner was docked for his clothes, tools, room and meals, and came to feel as though he were working for the privilege of being allowed to live, the scrappers’ game is rigged against them. In time, the junkyard horse seems analogous to the humans it serves: a beast of burden valued only for the weight it can bear.

“The Selfish Giant” may remind you of other films about childhood under harsh circumstances, none of which, to put it mildly, were upbeat: “Killer of Sheep,” “Sounder,” “Los Olvidados,” “Panther Pachali” and “Kes.” It’s not on the level of those inspirations—its doom-spiral story feels contrived in places—but there’s no denying its effectiveness. The film is a tragedy: keenly observed, warm, often funny, but a tragedy. And yet even when the life-on-rails dramaturgy becomes wearisome, we feel we’re watching an evil adult exploit angelic children. Arbor and Swifty aren’t “good” or “bad” boys, just desperate and far too trusting. Kitten isn’t a villain, just a mangled product of his environment like everyone else.

This is a social realist drama of the sort that another English filmmaker, Ken Loach, has been making for decades, but less didactic in how it reveals the political and economic dimensions of its characters’ lives. It’s about how an extended village made up of local, regional and national governments fails two boys, their families and their communities. The school and social service employees who are supposed to monitor at-risk kids are so overworked, poorly trained or under-supported that all they can do is reflexively punish problem kids, or look away as they disrupt class and commit petty crimes. Kids and adults alike taunt each other for not being “hard” enough. We get the sense that all of these characters wouldn’t be so tough, sometimes cruel, if the economy offered them a way to live in dignity and peace.

At certain points, the relationship between Arbor and Swifty may remind you of John Steinbeck’s “Of Mice and Men,” but in this version of the story, the little one is the unpredictable, emotionally limited outcast, and the big one is his guardian and minder, and they’re both just boys who should be thinking of the future, not slaving away in the present. Their fate should not have been a foregone conclusion, and there’s plenty of blame to go around. “If a fella steps on a round pebble and he falls down, breaks his neck, it ain’t the pebble’s fault,” George says in the novel, “but the guy wouldn’t a done it if the pebble hadn’t been there.”