“The Santa Clause” provides at least one valuable service: It explains exactly how Santa is able to get down chimneys that are too small for him, and how he is able to enter apartments through hot water radiators and heating vents. There is also an intriguing theory, handled in a throwaway line of dialogue, to explain how Santa is able to visit everybody’s house on Christmas Eve. It may have something to do with parallel time tracks, or other concepts of advanced physics.

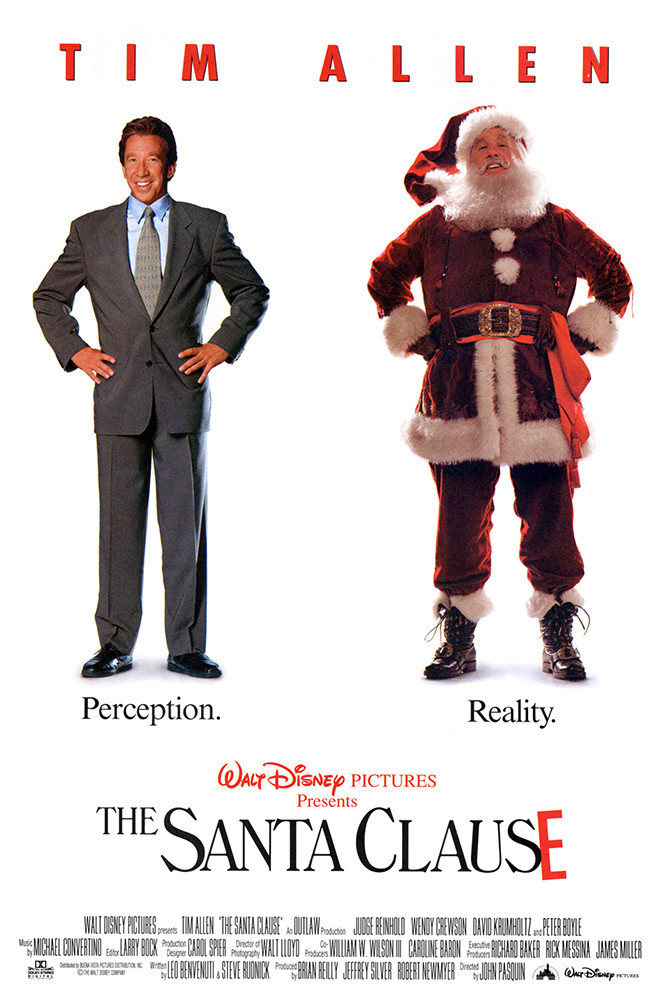

We also learn that being Santa is not a job for eternity, but that, instead, there are various office holders, just like for country coroner or recorder of deeds. As the movie opens, Scott Calvin (Tim Allen, of TV’s “Home Improvement”) is a man who does not believe in Santa Claus. But then up on the rooftop there arises such a clatter, that Scott and his son, Charlie (Eric Lloyd), run into the yard to see what is the matter. And what to their wondering eyes should appear, but a great big sleigh and eight giant reindeer, up on the house.

And then, when Scott’s shout startles Santa, he loses his balance and is killed in a fall from the roof. After which Scott finds a card in his pocket notifying the bearer that he is the new Santa Claus. Before Scott quite realizes what has happened, the old Santa has disappeared, and he is wearing the suit and going down the chimneys.

The premise for “The Santa Clause,” written by Leo Benvenuti and Steve Rudnick and directed by John Pasquin, is a clever one, and the movie is not without real charm. One of its innovations is to provide us with a stepfather who is not a monster: Scott and his wife, Laura (Wendy Crewson) are divorced, and Laura’s new husband Neal (Judge Reinhold) is a psychiatrist, who takes a dubious position on the subject of Santa’s reality, but is otherwise a fairly nice guy.

As the movie continues, Scott finds himself learning all the tricks of the Santa trade, including how to handle unfriendly dogs in strange living rooms. Certain symptoms develop: He puts on weight, from all the milk and cookies people leave out for him, and is able to grow a flowing beard in just a few days. And there are sly contemporary references, as when he suggests to one little girl that the milk put out for him tastes a little funny, and she explains it’s soy milk – because on last year’s visit he complained of lactose intolerance.

At the North Pole, Scott, in his new role, finds a workshop humming along under the leadership of Bernard, the head elf (David Krumholtz), who likes to do things his way, and has a good line: “We’re your worst nightmare: Elves with attitude.” But at home, his conviction that he is actually Santa makes him into a subject for psychiatric attention.

“The Santa Clause” (so named after the clause on Santa’s calling card that requires Scott to take over the job) is often a clever and amusing movie, and there’s a lot of fresh invention in it.

If I found my attention flagging, maybe it’s because I am not a member of its intended audience. For kids and many teenagers and their families, this is probably going to be a popular film. I personally found I just didn’t care much: That, despite its charms, the movie didn’t push over the top into true inspiration. I would have traded a lot of “The Santa Clause” for just one shot of Groucho Marx explaining how there ain’t no sanity clause.