Side by side on a shady suburban street, in houses like temples to domestic gods, three families marinate in misery. They know one another, but what they don’t realize is how their lives are secretly entangled. We’re intended to pity them, although their troubles are so densely plotted they skirt the edge of irony; this is a literate soap opera in which beautiful people have expensive problems and we wouldn’t mind letting them inherit some undistinguished problems of our own.

To be sure, one of the characters has a problem we don’t envy. That would be Paul Gold (Joshua Jackson), a bright and handsome teenager who has been in a coma since an accident. Before that he’d been having an affair with the woman next door, Annette Jennings (Patricia Clarkson), so there were consolations in his brief conscious existence.

Now his mother Esther (Glenn Close), watches over him, reads to him, talks to him, trusts he will return to consciousness. His father Howard (Robert Klein) doesn’t participate in this process, having written off his heir as a bad investment, but listen to how Esther talks to Howard: “You never even put your eyes on him. How do you think that makes him feel?” The dialogue gets a laugh from the heartless audience, but is it intended as funny, thoughtless, ironic, tender, or what? The movie doesn’t give us much help in answering that question In a different kind of movie, we would be deeply touched by the mother’s bedside vigil. In a very different kind of movie, like Pedro Almodovar’s “Talk to Her,” which is about two men at the bedsides of the two comatose women they love, we would key in to the weird-sad tone that somehow rises above irony into a kind of sincere melodramatic excess. But here–well, we know the Glenn Close character is sincere, but we can’t tell what the film thinks about her, and we suspect it may be feeling a little more superior to her than it has a right to.

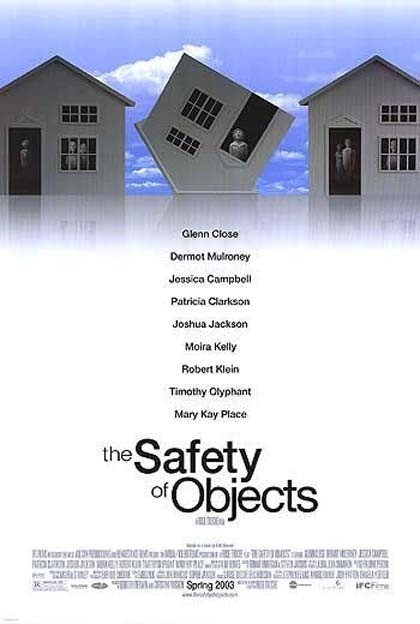

Written and directed by Rose Troche, based on stories by A. M. Homes, “The Safety of Objects” hammers more nails into the undead corpse of the suburban dream. Movies about the Dread Suburbs are so frightening that we wonder why everyone doesn’t flee them, like the crowds in the foreground of Japanese monster movies.

“The Safety of Objects” travels its emotional wastelands in a bittersweet, elegiac mood. We meet a lawyer named Jim Train (Dermot Mulroney), who is passed over for partnership at his law firm, walks out in a rage, and lacks the nerve to tell his wife Susan (Moira Kelly). Neither one of them knows their young son Jake (Alex House) is conducting an affair–yes, an actual courtship–with a Barbie doll.

Next door is Helen (Mary Kay Place), who, if she is really going to spend the rest of her life picking up stray men for quick sex, should develop more of a flair. She comes across as desperate, although there’s a nice scene where she calls the bluff of a jerk who succeeds in picking her up–and is left with the task of explaining why, if he really expected to bring someone home, his house is such a pigpen.

Let’s see who else lives on the street. Annette, the Clarkson character, makes an unmistakable pitch to a handyman, who gets the message, rejects it, but politely thanks her for the offer. Annette is pathetic about men: She forgives her ex-husband anything, even when he skips his alimony payments, and lets a child get away with calling her a loser because she can’t afford summer camp.

What comes across is that all of these people are desperately unhappy, are finding no human consolation or contact at home, are fleeing to the arms of strangers, dolls or the comatose, and place their trust, if the title is to be believed, in the safety of objects. I don’t think that means objects will protect them. I think it means they can’t hurt them.

Strewn here somewhere are the elements of an effective version of this story–an “Ice Storm” or “American Beauty,” even a “My New Gun.” But Troche’s tone is so relentlessly, depressingly monotonous that the characters seem trapped in a narrow emotional range. They live out their miserable lives in one lachrymose sequence after another, and for us there is no relief. “The Safety of Objects” is like a hike through the swamp of despond, with ennui sticking to our shoes.