“Glory” apart, we’ve seen few movies that focus on the travails of African-Americans during the Civil War, so Chris Eska’s ingenious, engrossing “The Retrieval” is a welcome addition to a small canon. Set in the crucial time between the struggles over emancipation depicted in Spielberg’s “Lincoln” and the war’s end in the spring of 1865, the drama brings the atmospheric tensions of a Faulkner novella and an indie film’s more-with-less aesthetic to the story of three black males swept up in the confusion and violence of a war lurching toward its climax.

Eska’s tale appears to be set in Virginia, though it was shot in his native Texas. The important point, though, is not where but when. Union forces are bearing down on the crumbling Confederacy, where many blacks remain enslaved, some have already escaped and others are caught up in the encroaching war’s fog, its brutal back-and-forth.

Southern slave hunters nonetheless still ply their merciless trade. The story opens when Will (Ashton Sanders), a 13-year-old black boy, comes up to a farm and asks to be sheltered with other escaped slaves who are hiding there. His plea hides a treacherous intent. When the others are asleep, he betrays them to the slave hunter Burrell (Bill Oberst Jr), who returns them to captivity.

Burrell’s hold on Will is that he has possession of his uncle, Marcus (Keston John). Though Marcus is gruff and demanding, he appears to be Will’s only available relative, so the boy clings to him even after Burrell gives him a harsh assignment. Burrell wants to capture an escaped slave named Nate (Tishuan Scott), with the intention of killing him to collect a bounty. So, Marcus is ordered to cross into Union territory and lure Nate back. If he succeeds, he’ll get a reward that will buy him a new life. If he shirks the task or fails at it, Burrell promises to hunt him down and kill him.

Would anyone in Marcus’ position actually let a threat like Burrell’s compel him to return to slaveholding territory once he’s made it to freedom? Though the plausibility of this plot point (a similar one arises later, when Will finds shelter behind some fighting Union soldiers, then abandons it in a way that puts him in danger again) may seem debatable, it also arguably reflects the power that the slaveholding ethos and its terrors had over the minds of its victims, as well as the complexities of the war at this point.

In any case, when Marcus and Will finally locate the muscular, taciturn Nate, they tell him his brother is dying behind enemy lines and wants to see him. Torn at first, Nate decides to make the dangerous trek but says he will do it on his own. It takes some persuasive talking on Marcus’ part to get Nate to agree to let them show him the way to his brother. So begins a journey into the war zone that’s complicated from the first by the fact that Nate takes an instinctual dislike to Marcus. As they travel, though, he develops a bond with the earnest, vulnerable Will, one that becomes crucial when this tale of treachery versus solidarity, and of one boy’s awakening conscience, reaches its tense climax.

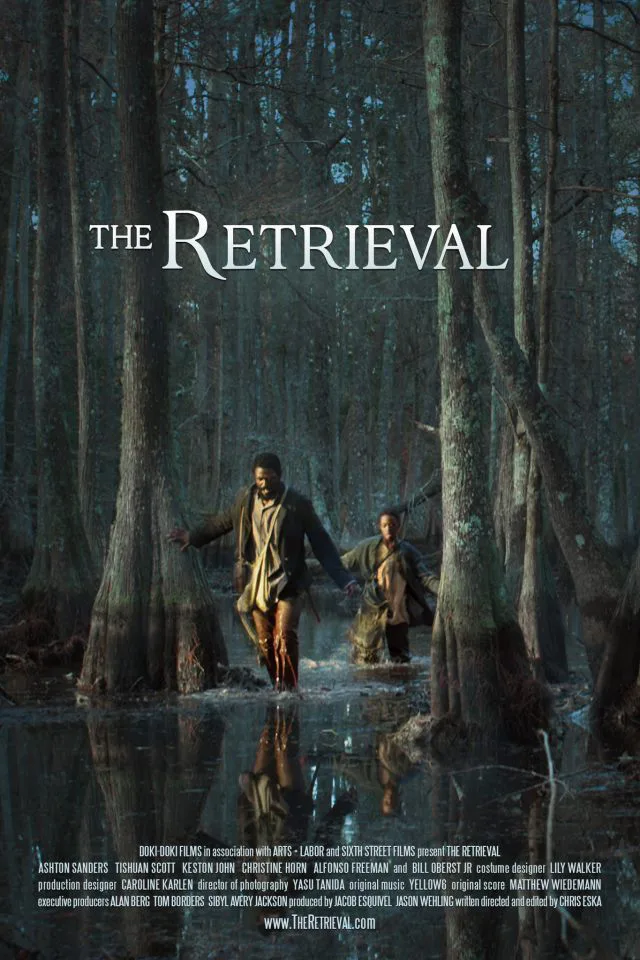

One of the chief virtues of Eska’s handling of this material is his eye for landscapes. The countryside traversed by the three characters is rendered with a subtly lyrical exactitude. It is beautiful in some moments, desolate or threatening in others, but always evocative of the wartime setting that conditions and mirrors the characters’ mounting dilemmas.

Both in its structure and its dialogue, Eska’s writing is similarly adroit, and he matches those accomplishments with the topnotch performances he gets from his three leads. As Will, newcomer Ashton Sanders has a young deer’s wide-eyed tentativeness, yet also an emerging strength that presages his passage into manhood. As Marcus, Keston John skillfully emphasizes the man’s selfish determination to serve only his own ends, while also suggesting the fear that underlies that hardness. And Tishuan Scott as Nate delivers a truly charismatic and prize-worthy performance as a strong man who has suffered deeply but who has not allowed the cruelties of slavery and war to rob him of his dignity and goodness.

Perhaps the only reservation to be registered about this estimable production concerns its photography. Not that Yasu Tanida’s digital images are anything less than clear, sharp and expertly rendered. That’s the problem. More than any film in recent memory, “The Retrieval” made this reviewer yearn for the subtle softness and subliminal flicker of celluloid, as opposed to digital’s sometimes overbearing brightness and clarity. No doubt this has to do in part with the story’s period setting, but it’s something for filmmakers to consider: Maybe when it comes to depicting 19th century subjects, the 20th century’s favorite moviemaking technology has certain imaginative advantages over its dubiously superior 21st century successor.