In 1958, an old man in a big old car begins a journey across England to the sea. His name is Stevens, and for many years he has been the head butler at Darlington Hall, a famous country house. He is going to visit a woman he has not seen in a long time: Miss Kenton, who was once the housekeeper at Darlington. He thinks perhaps she can be persuaded to resume her old position under the hall’s new owner, a retired American congressman.

Both Stevens and Darlington Hall are anacronisms. Stevens comes from a tradition of personal service; his goal in life is to serve his employer to the best of his ability, and as we get to know him, we realize that this was his only goal: He allowed it to blind him to all of the other promises of life.

“The Remains of the Day” tells the story of Stevens’ trip to the sea, and what he finds there. Along the way, in flashback, we see his memories of the great days at the hall, when Lord Darlington played host to the world’s leaders, and it seemed at times the future of Britain was being decided. And slowly we begin to realize that things were not as they seemed, that Darlington was not as wise as he thought, that Stevens was blind to the reality around him.

“The Remains of the Day” is based on the Booker Prize novel by Kazuo Ishiguro, which I would have thought almost unfilmable, until I saw this film. So much of it takes place within Stevens’ mind, and it is up to the reader to interpret what the butler remembers: To deduce reality through the filter of a narrow, single-minded man. The reality is that Lord Darlington, in the years before World War II, had great sympathy for Germany, and hoped to bring about a separate peace between Britain and the Nazis. In this he was not precisely evil; he was deluded, short-sighted, easily persuaded by the pieties of genteel racism. He was, as a dinner guest brutally informs him, an amateur, who should have left international relations to the professionals.

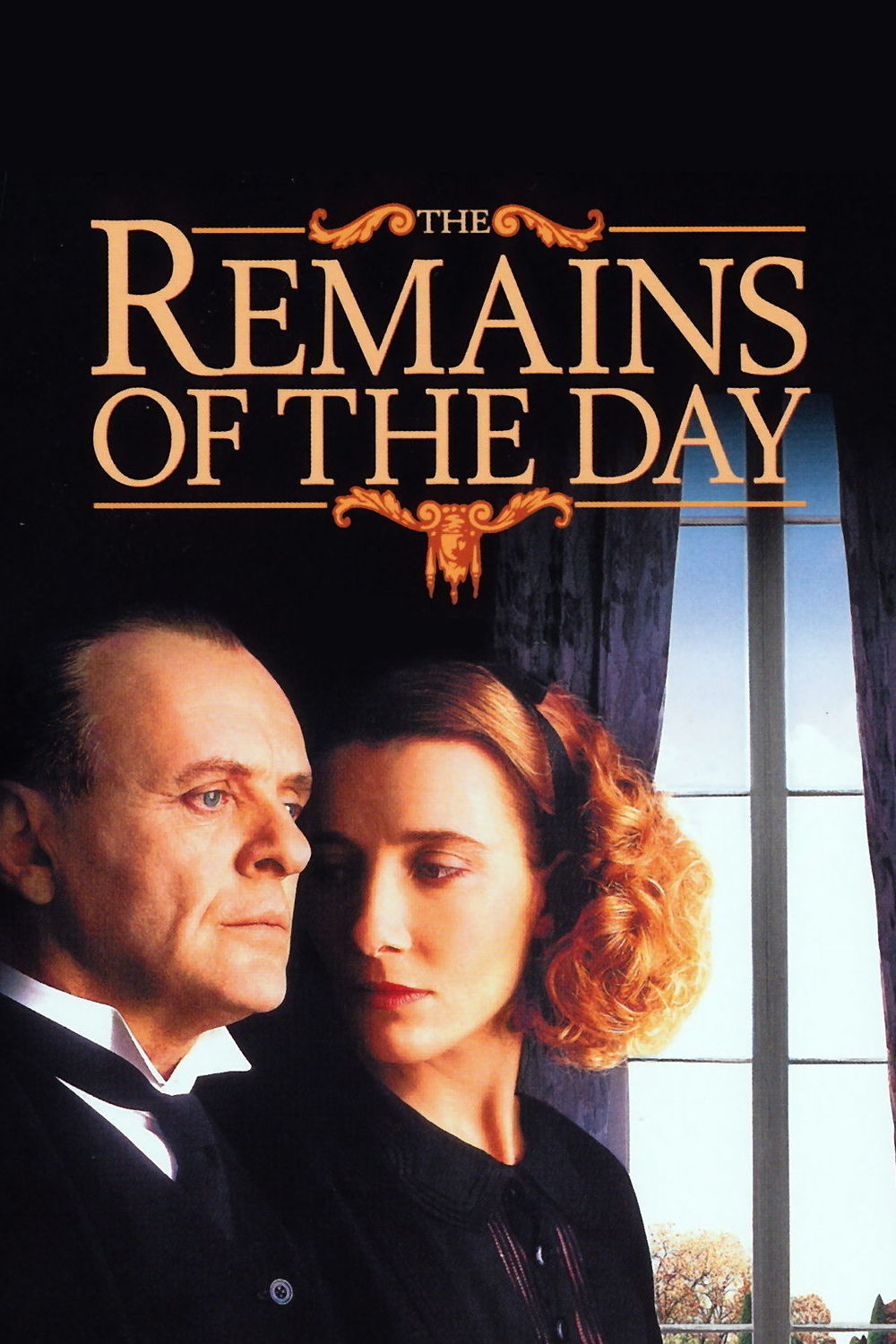

The movie has been made by the team of director James Ivory, producer Ismail Merchant, and writer Ruth Prawer Jhabvala. After “A Room with a View” and “Howards End,” they are at the height of their powers, taking us inside a society where tradition is valued, even at the cost of repressing normal human feelings. The feelings, for example, that Stevens (Anthony Hopkins) might be expected to feel for Miss Kenton (Emma Thompson).

In a British country house of the period, the head butler and the housekeeper would have been equals, roughly speaking, each supervising the two major realms of service. Miss Kenton is clearly attracted to the butler, but he is terrified of intimacy, and sidesteps it through a fanatic devotion to his work. The film demonstrates this in a series of quiet, almost secretive scenes, in which she pushes, and he flees. The most painful, and brilliant, shows Miss Kenton surprising Stevens in his room, reading a book.

What book? she asks. He hides the cover. She pursues him, cornering him, snatching the book away to find it is a best-selling romance.

She had not imagined he read romances! He only reads, he stiffly explains, to improve his vocabulary.

Does Stevens possess any ordinary human feelings? Quite possibly, but something has led him to bury them. We meet his father (Peter Vaughan), himself a butler, who reared the son to a rigid idea of service – so rigid that when the father is actually dying upstairs, Stevens does not abandon his post at an important dinner party.

The motor journey unfolds, as incident and memory reveal one secret after another. We begin to understand the nature of Darlington’s behavior. The lord (played by that most urbane and civilized actor James Fox) is not a worldly man (he even recruits Stevens to explain “about the birds the the bees” to a godson who is obviously far beyond a zoological approach to sex). Cultivated and flattered by Nazi sympathizers and anti-Semites, he sponsors “international conferences” that will eventually lead to Darlington Hall being described as a traitor’s nest. Does Stevens hear what is discussed at the meetings where he serves? What does he think about it? It is not the butler’s place, he explains, to listen to his employer’s conversations, or form opinions of them.

As the political disaster of Darlington Hall unfolds, a personal disaster also is in the making. Miss Kenton, discouraged in her approaches to Stevens, eventually bolts from her job. And it is only many years later that she contacts Stevens again, by letter, leading to his motor trip. Perhaps at some place buried deep in the darkness of his hopes, there is the thought that she might . . . still be interested in him? The closing scenes paint a quiet heartbreak. The whole movie is quiet, introspective, thoughtful: A warning to those who put their emotional lives on hold, because they feel their duties are more important. Stevens has essentially thrown away his life in the name of duty. He has used his “responsibilities” as an excuse for avoiding his responsibility to his own happiness.

“The Remains of the Day” is a subtle, thoughtful movie. There are emotional upheavals in it, but they take place in shadows and corners, in secret. It tells a very sad story – three stories, really. Not long ago I praised a somewhat similar film, Martin Scorsese’s “The Age of Innocence,” also about characters who place duty and position above the needs of the heart. I got some letters from readers who complained the movie was boring, that “nothing happens in it.” To which I was tempted to reply: If you had understood what happened in it, it would not have been boring.