Pacho Velez and Sierra Pettengill’s “The Reagan Show” is a 74-minute nonfiction film comprised entirely of newsreel and video footage from Ronald Reagan’s presidency. Given that its subject was a very divisive figure—despite what some latter-day mythologies would suggest—one might well wonder whether it’s pro-Reagan or anti-Reagan. The answer: neither. Or rather, both Reagan lovers and Reagan haters will find enough in the film to bolster their perspectives. Even more remarkably, it’s almost entirely snark-free.

At a time when sharp ideological stances are annoyingly ubiquitous, this film’s lack of one is refreshing. But my commendation comes with a caveat for people who may have slept through the Reagan presidency, or those too young to remember it. While the film does offer a chronicle of Reagan’s eight years in office, it focuses mainly on one aspect of that history. Much is left out. To take one of many possible examples, there’s no mention of Reagan’s disastrously underwhelming response to the AIDS crisis, which left many people dead and many others apoplectic with anger. Of the Iran-Contra scandal you hear a bit, but it never gets to the Congressional hearings that put military martinet Col. Oliver North in America’s living rooms for too many evenings running. The names of Lebanon, Nicaragua, Grenada and Afghanistan are never heard. And so on.

The aspect of Reagan’s time in office the film chooses to highlight is his stance toward the Soviet Union and especially his evolving relationship with Soviet premier Mikhail Gorbachev, which eventually produced a landmark nuclear arms-reduction treaty. Yet it wouldn’t be accurate to say that this is the film’s subject. Rather, the filmmakers seem most interested in using the US-USSR story as a way of suggesting how every aspect of Reagan’s presidency was bound up with his sense of televisual performance.

John F. Kennedy is sometimes called the first TV president, mostly because his 1960 election was the first in which television was seen to have had a big, perhaps decisive impact on the outcome, and because his movie-star looks were so TV-friendly. But JFK himself was a product of the pre-TV age, as were three subsequent presidents who were effectively unseated by the new medium: Lyndon Johnson by its coverage of the Vietnam War; Richard Nixon by the televised Watergate Hearings; and Jimmy Carter by year-long horror show known as the Iran Hostage Crisis, which bequeathed us the show “Nightline.”

Reagan was the first real TV president in that he not only was suited to and mastered the medium but literally emerged from it—like a phantasm jumping out of a cathode tube’s fluorescent ether in an episode of “Twin Peaks.” While “The Reagan Show” gives us clips of some of Reagan’s 53 movies as actor in which he forged his image as an all-American hero, it doesn’t note his career as a corporate pitchman for General Electric and host of TV’s “Death Valley Days.” The latter may well have been more crucial to his political career than the former. At least, the Hollywood hero content could not have been put across so successfully without the Madison Avenue polish that Americans had been absorbing mentally via TV for a generation when Reagan ran for president in 1980.

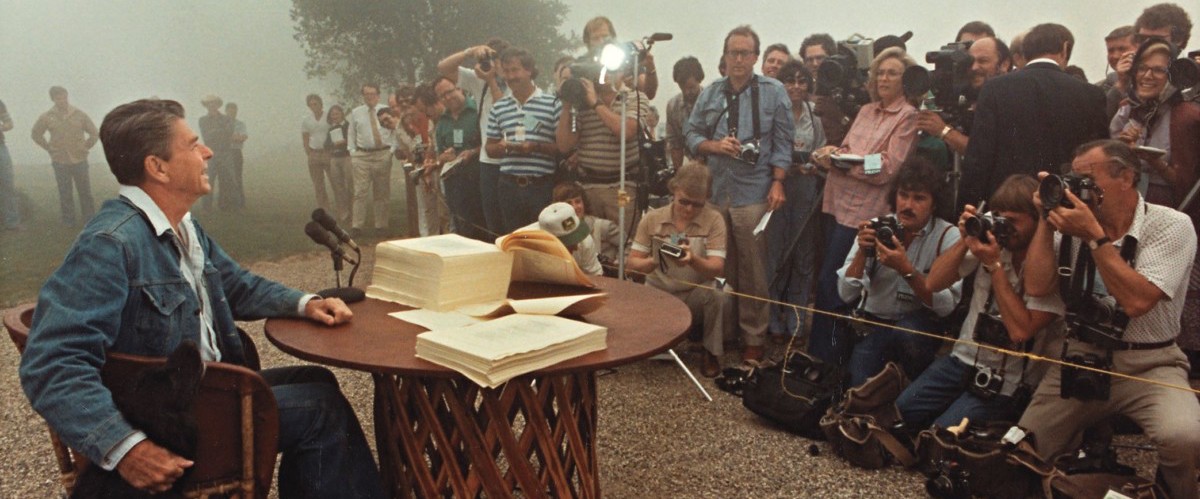

In some of the contemporary news reports in “The Reagan Show,” we hear of Reagan’s laziness, vacuousness, disengagement, and so on. It’s said that he spent one third of his time working on stuff and two-thirds selling it. But boy, could he sell; that folksy grin and square-jawed aw-shucks manner could have put over anything from shampoo to suicide. That was what was scary about him then and now: the sense that style always ran roughshod over substance in the Reagan ethos.

Did he really believe anything that was beyond a sales pitch? Here’s perhaps a better question: Was Reagan’s mind so deeply conditioned by Hollywood myths and his old movie roles that, on some level, he couldn’t distinguish between those fictions and reality? And: if George Lucas hadn’t made a certain silly sci-fi movie a few years before Reagan became president, would he have become obsessed with a program for militarizing outer space that was nicknamed “Star Wars,” an idea even more cuckoo and costly than that of building a wall along the U.S.-Mexico border?

The “Star Wars” fantasy-reality conundrum may well bedevil historians for decades to come. In “The Reagan Show” we hear Star Wars denounced for its impracticality, its expense and especially its inevitable way of producing a new arms race. None of this swayed Reagan. But the obsession did soon run into a new reality. The reformist Gorbachev—also a skilled manipulator of images—was in charge in Moscow and making nice with western leaders. Would Reagan meet him? Would he listen to him, especially on the touchy subject of arms control?

“The Reagan Show” documents the various meetings of the two leaders over two years and how a rapport and guarded respect between them helped lead to a plan to eliminate all nuclear weapons by the year 2000—though, significantly, Star Wars was kept off the table (obsessions die hard). This section of the film convinced me that Reagan was a tough, shrewd and informed negotiator, as well as a president who wanted peace as part of his legacy. Ironically, his own party despised his “appeasement” while Democrats cheered it. And it would be left to future Republican presidents—including one birthed from reality TV—to trash that treaty and begin a new arms race.