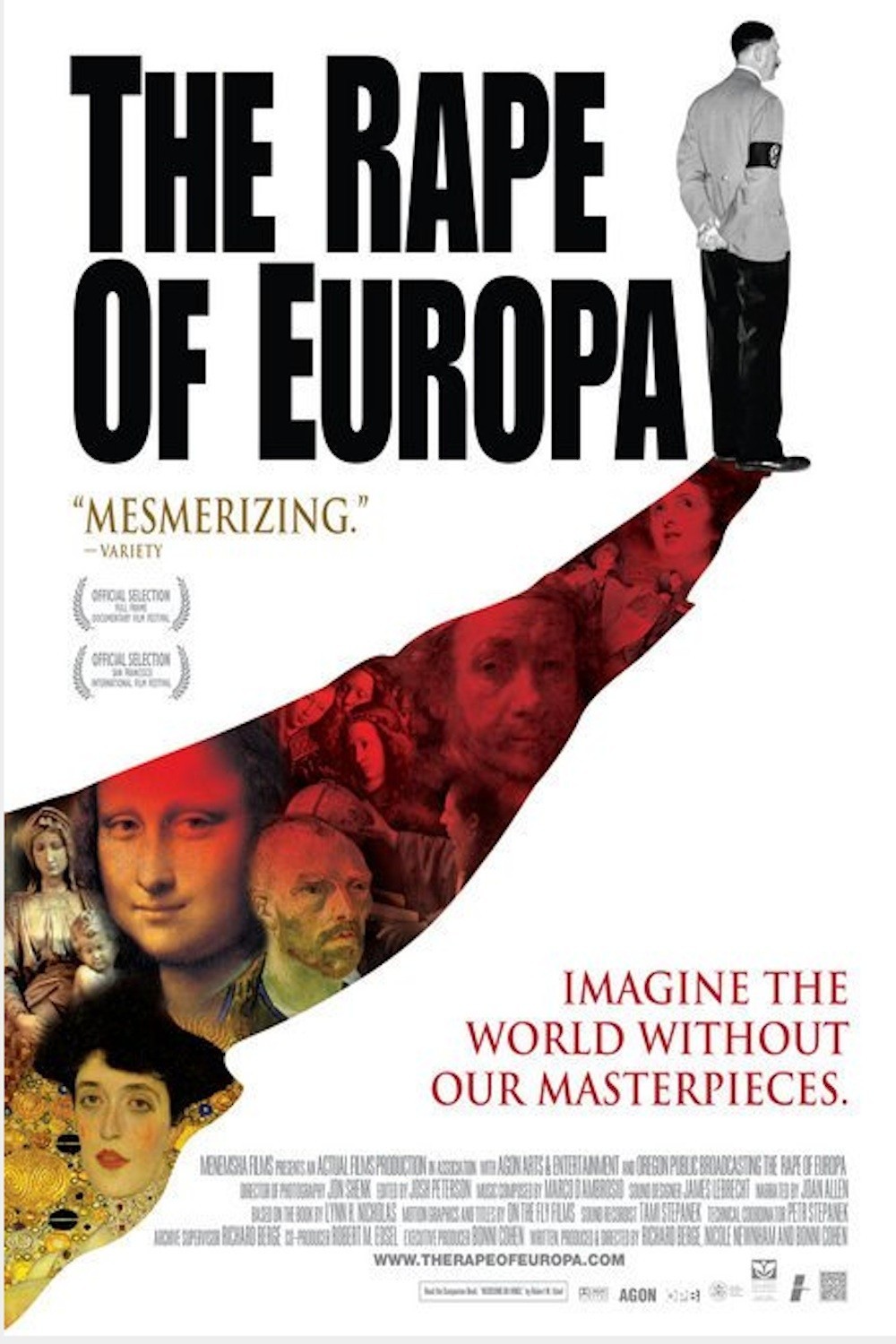

We know the Nazis looted art from the nations they overran. Maybe we’ve seen “The Train” (1964) and know how one shipment was thwarted. But how many important paintings, sculptures and other artworks would you say the Nazis made off with? Hundreds? Thousands?

“The Rape of Europa,” a startling documentary, puts the number rather higher: One-fifth of all the known significant works of art in Europe — millions. Incredibly, Hitler maintained shopping lists of art for every country he invaded, and dispatched troops to secure (i.e., plunder) the works and ship them back to Germany. He had plans to build a monumental art museum in Linz, his Austrian birthplace, and was working on models of the structure even during his final days in the Berlin bunker. His right-hand man Hermann Goering was no less keen as a collector.

That Hitler was mad is well known. That he was mad about art, not so well. He was in his youth an ambitious painter, and applied to an art school in Vienna, but was rejected. The general outline of his early art career, somewhat fictionalized, can be seen in “Max,” a little-noticed 2002 film starring Noah Taylor as Hitler and John Cusack as a one-armed Jewish art dealer in Munich, who befriends Hitler, his liquor deliveryman.

Hitler’s art was not good (we see some landscape water colors), and his taste in art was terrible. He had a weakness for heroic Nordic supermen and women in a style of uber-kitsch, and believed modern art was Jewish and decadent. In addition to the artworks he looted, he ordered the destruction of countless others; not all of those Nazi bonfires consumed only books.

This absorbing documentary begins with one painting, Gustav Klimt’s “Gold Portrait of Frau Bloch-Bauer,” which, like countless other paintings, was stolen from Jews, disappeared, and then mysteriously reappeared in galleries and museums in Europe and America with shadowy provenance. Maria Altmann, the niece of the man who commissioned the painting, waged a long legal battle to have possession returned to her, and won; when the painting was later sold at auction, its price of $135 million set a record.

But until recently, many possessors of stolen artworks have chosen to ignore claims by their original owners, and only now is an international tracing operation underway. It is believed that countless priceless works languish in the shadows of private homes, discreetly kept out of sight. Work is only beginning on a central clearing-house of information.

Many other works of sculpture and architecture were destroyed by the bombing raids of both sides, although an occasional exception was made; the city of Venice, for example, was spared by American bombers. Much praise is given to the “Monument Men,” American art experts enlisted into the army and deployed under the orders of Eisenhower to identify and protect the surviving heritage of liberated nations. In stark contrast, American bombs destroyed museums in Baghdad and throughout Iraq, and others were looted; no effort was made by our commanders to preserve the treasures.