Austere and old-fashioned almost to a fault, “The Railway Man” offers tastefully safe treatment of a horrific subject: the torture of a British Army officer at a Japanese prisoner of war camp during World War II.

Director Jonathan Teplitzky’s film remains respectable and restrained until the very end—but the performances are so strong and the ultimate catharsis that occurs is so palpable that it sneaks up on you with an unexpected emotional wallop. This is a true story—or as true as a feature film about anyone’s life can be—and it’s one that’s worth telling, with an angle on World War II that movies don’t offer very often.

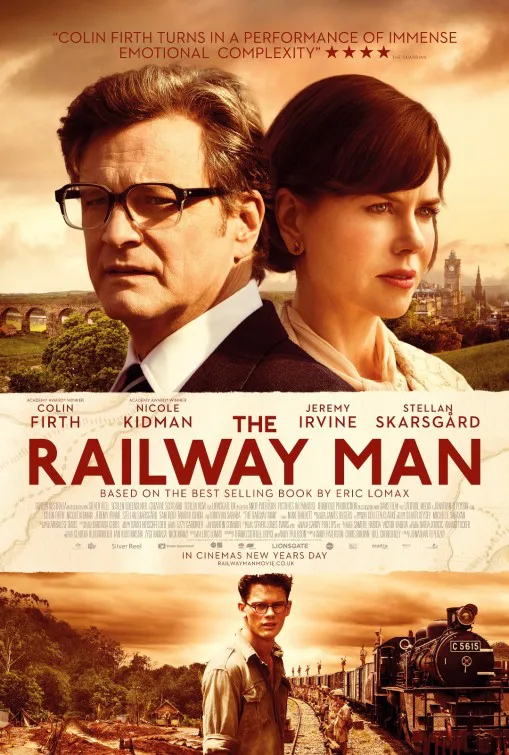

What’s not surprising is the subtlety Colin Firth finds in playing Eric Lomax, whose autobiography inspired “The Railway Man.” (Frank Cottrell Boyce and Andy Paterson co-wrote the screenplay.) Playing Lomax as a shell of his former self decades after his imprisonment, Firth is both quietly distracted and fitfully tormented. Throughout his career, Firth repeatedly has proven himself to be a master at steadily revealing his characters, and the way his Lomax eventually reclaims his identity before enjoying some redemption is gently stirring.

Lomax also finds some fleeting moments of tentative joy with the love of his life, whom he encounters in middle age: his wife, Patti, played by Nicole Kidman in an underwritten role. Kidman is kind of charming at first as she flirts with and falls for Firth. But in no time, she’s relegated to serving as the teary-eyed wife, listening to what happened to her husband and whispering responses of shock and sadness.

In the annoying framing device that flashes back and forth in time far too frequently, we see Lomax and Patti meet cute on a train. The year is 1980 in Northern England. He is nerdy, tweedy, hurried. She is prim, sharp, poised. He’s an expert on trains—an “enthusiast,” to use his word. She’s a former nurse. Both are in flux and clearly a little fragile. As they wind their way along the English and Scottish coast, he drops little tidbits about various train lines and trivia on the towns that blur past them. She’s chatty and charming in response.

“Don’t move,” Lomax says as Patti stands in his cramped kitchen on her first visit to his apartment. “Why not?” she asks. “’Cause I’m looking at you.”

Individually lonely, alone and adrift, they fall in love and get married in no time. But on what should be the happiest day of his life, Lomax is haunted by nightmarish memories of the brutality he endured as a POW—a condition we now know as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. It’s not something he and the other veterans at the Officers Club, including his close friend and fellow ex-prisoner Finlay (Stellan Skarsgard), ever talk about.

Flashing back in time, Lomax (played by Jeremy Irvine as a younger man) recalls being taken into custody after the fall of Singapore in 1942. There, he and the other soldiers were forced into slave labor, working on the Burma-Siam “Death Railway,” as it became known. Being smart and clever, Lomax became a target of his sadistic Japanese captors, who are all depicted as one-dimensionally evil. (Irvine is a strong casting choice, though; not only does he resemble a young Firth, he’s also adept at radiating a steely resilience through nervousness.)

“The Railway Man” jumps back and forth between Lomax and Finlay remembering this harrowing time and images of the torture itself. This included being beaten, kicked, waterboarded and locked up in a bamboo cage the size of a large dog crate. Teplitzky depicts it all in an artfully staged and lighted fashion. One Japanese officer in particular, the translator Nagase (Tanroh Ishida), arbitrarily reveled in finding new accusations against Lomax and overseeing his destruction.

But unlike the many other men who suffered beside him, Lomax somehow managed to survive. So when he learns nearly 40 years later that Nagase also is alive, and has turned the camp where he helped torture all those men into a war museum, Lomax knows he must return to Southeast Asia to confront his demons, both literally and figuratively.

The scenes between Lomax and Nagase (played as an older man by Hiroyuki Sanada) are fraught with unpredictability and tension. Firth really comes into his own in this section of the film, but Sanada is his equal as he goes through a spectrum of emotions: denial, defensiveness, fear, remorse and—ultimately—forgiveness, something both men get to enjoy at long last.