The positive but puzzled reviews for “A.I. Artificial Intelligence” all agreed on one thing: The film was the work of an artist. I feel more positive and less puzzled about “The Princess and the Warrior,” which is also the work of an artist. Both titles are reminders that it is better to see an imperfect movie that lives and breathes than a perfect one which is merely a genre exercise.

“The Princess and the Warrior” is one astonishment after another. It uses coincidence with reckless abandon to argue that deep patterns in life connect some people. It uses thriller elements–not to thrill us, but to set up moral challenges for its characters. It is about a woman convinced she has met the one great love of her life, and a man convinced he is not that person. It is about a traffic accident, a bank robbery, an insane asylum, and it does not use any of those elements as they have been used before. Above all, it loves its characters too much to entrap them in a mediocre plot.

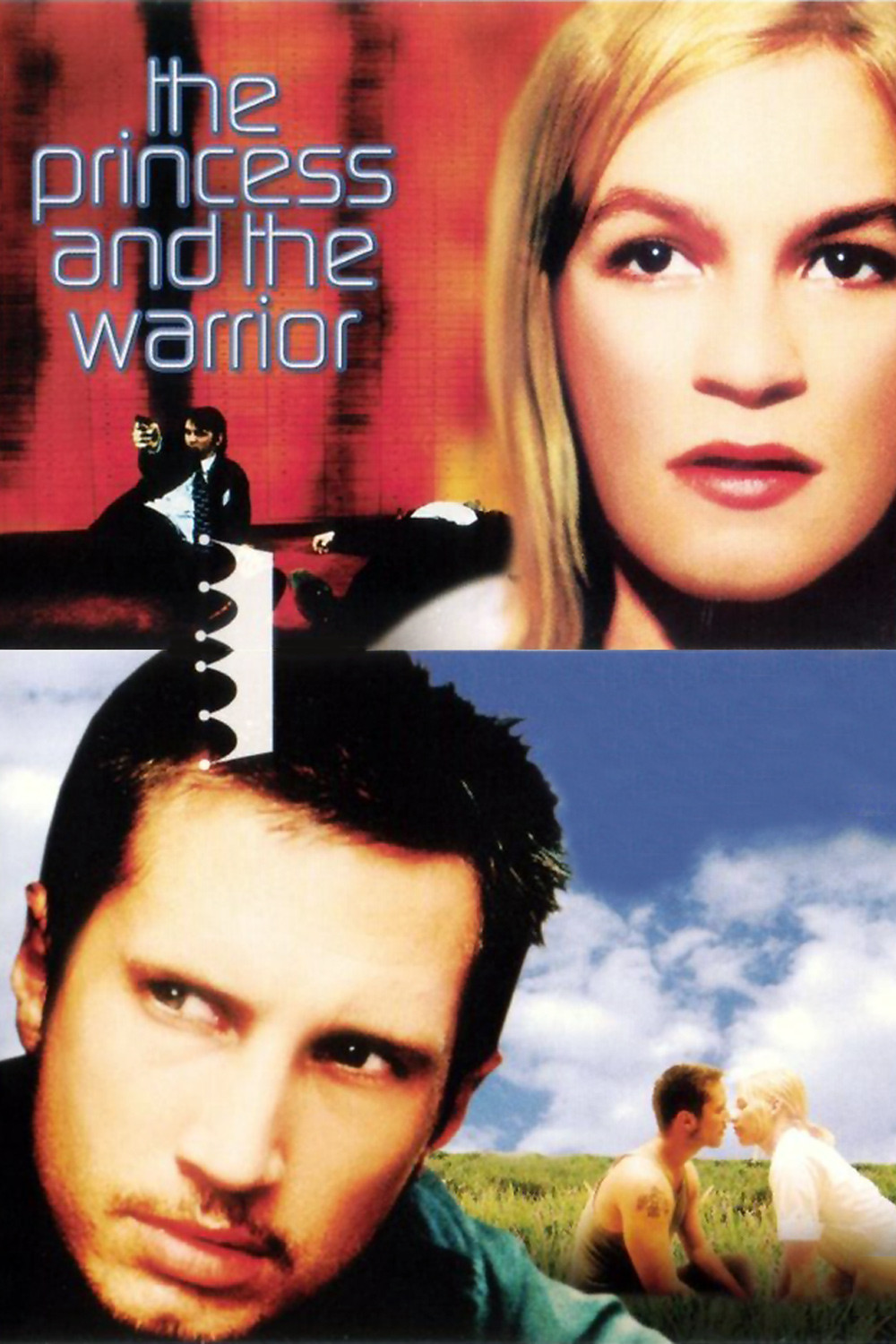

The movie was written and directed by Tom Tykwer, from Germany, who had international success with “Run Lola Run,” and now has made a deeper and more ambitious film. It stars Franka Potente, who played Lola (she was also the stewardess married to Johnny Depp in “Blow“). It uses the same kind of crazy looping energy as “Lola,” and is just as open to intersecting fates, but “Lola” was essentially about kinetic energy, and this is a film about the thin membranes that separate life and death, good and evil, success and failure, love and fear.

Potente plays Sissi, a nurse in the psychiatric hospital, much loved by her strange patients, and so shut off from the outside world that when she shares a secret erotic moment with one of them, we sense they’re performing a mutual service. Her co-star is Benno Furmann, who plays Bodo–a bank robber, among other things.

They meet after Bodo unwittingly causes an accident that leaves Sissi pinned under a truck and choking on her own blood. He crawls under the truck to elude the police, sees that she is dying and saves her life. I will not tell you how he does this, except to say that the scene, in its horror, its detail, its quiet observation, its reliance on the soundtrack to tell us what is happening, is overwhelming in its intensity.

It shows greatness, not just because of what I’ve referred to, but by something more–the detail that Tykwer adds after the scene seems to be over. Let us say, without giving too much away, that events have made Sissi acutely aware of the nature of each breath she takes. She has been looking into the eyes of this man who is saving her, and now she becomes aware that his breath is sweet and has sent a “peppermint sting” to her lungs.

Bodo accompanies her into an ambulance (it is his means of escape from the police–every action in this movie seems to have two purposes). She holds desperately to his hand, then passes out, and later finds she has nothing but the button from his coat. He has disappeared. She knows she must find him. It is their destiny. Here is another astonishing scene. She knows a patient at the asylum, a blind man, who like many blind people is acutely aware of his surroundings and may be psychic. She asks him to retrace the route of the man who saved her life.

While all of this is going on, we learn more about an elaborate bank burglary being planned by Bodo and his brother Walter (Joachim Krol), and eventually the lives of Sissi and Bodo cross–not once, not just as a “coincidence,” but in a series of interlinking connections that take on a life of their own.

Tykwer uses the elements of genre in his film, but evades generic simplicities. He is using the conventions of a bank heist movie, not to make a bank heist movie, but to lay down a narrative map so that we can clearly see how the characters wander off of it–lose their way in the tangle of their lives and emotions. He looks at his characters a little harder than most directors; he isn’t content with one level of writing to describe them, but needs many. Consider an opening sequence in which Bodo is working as a gravedigger and laborer at a funeral home, and is fired for–what would you guess? Do you have an idea? He is fired for crying.

“The Princess and the Warrior” is not perfect. It is a little too long, and takes us an extra lap around its ironic track. But it’s so rich, how can we complain? Tykwer is 36 and this is his fourth feature. Like other directors of his generation, he’s fascinated by narratives that play with time; like “Memento,” “Amores Perros” and “One Night At McCool's,” his film is impatient with straight narratives and linear plots and wants to filter events through more than one point of view. That’s at the structural level. What’s special about the film is at a deeper level, down where he engages with the souls of his characters.