“Blow” stars Johnny Depp in a biopic about George Jung, a man who claims that in the late 1970s he imported about 85 percent of all the cocaine in America. That made him the greatest success story in drugs, an industry that has inspired more movies than any other.

So why is he such a sad sack? Why is his life so monotonous and disappointing? That’s what he’d like to know. The last shot in the film shows the real George Jung staring out at us from the screen like a man buried alive in his own regrets.

The story begins in a haze of California dreamin’ for George, who escapes West from an uninspiring Massachusetts childhood, a relentless mother (Rachel Griffiths) and a father (Ray Liotta) who doesn’t want to deal with bad news about his son. In the Los Angeles environs of Manhattan Beach, George smokes pot, throws Frisbees, meets stewardesses and engages in boozy plans with his friend Tuna (Ethan Suplee), who asks him, “You know how we were wondering how we were gonna get money being that we don’t want to get jobs?” The brainstorm: import marijuana from Mexico in the customs-free luggage of their stewardess pals and sell it to eager students at Eastern colleges. This is a business plan waiting to be born, and soon George is wealthy, although not beyond his wildest imaginings. His first love is a stewardess named Barbara (Franka Potente, from “Run, Lola, Run”), and it’s fun, fun, fun, and her daddy never takes her T-Bird away.

These opening chapters in the life of George Jung tell a story of small risk and great joy, especially if your idea of a good time is having all the money you can possibly spend and hopelessly conventional ideas about how to spend it. How big a house can you live in? How many drugs can you consume? George never actually planned to become a drug dealer and is a little bemused at his good luck. Even a 1972 bust in Chicago seems like a minor bump in the road (speaking in his own defense, he tells the judge, “It ain’t me, babe”).

Back on the streets, George finds clouds obscuring the California sun. Barbara dies unexpectedly (i.e., not because of drugs), and his success attracts the interest of a better class of narcotics cop. He becomes a fugitive, and it is his own mother who rats on him to the cops, even while his father is beaming at what might seem to be his success.

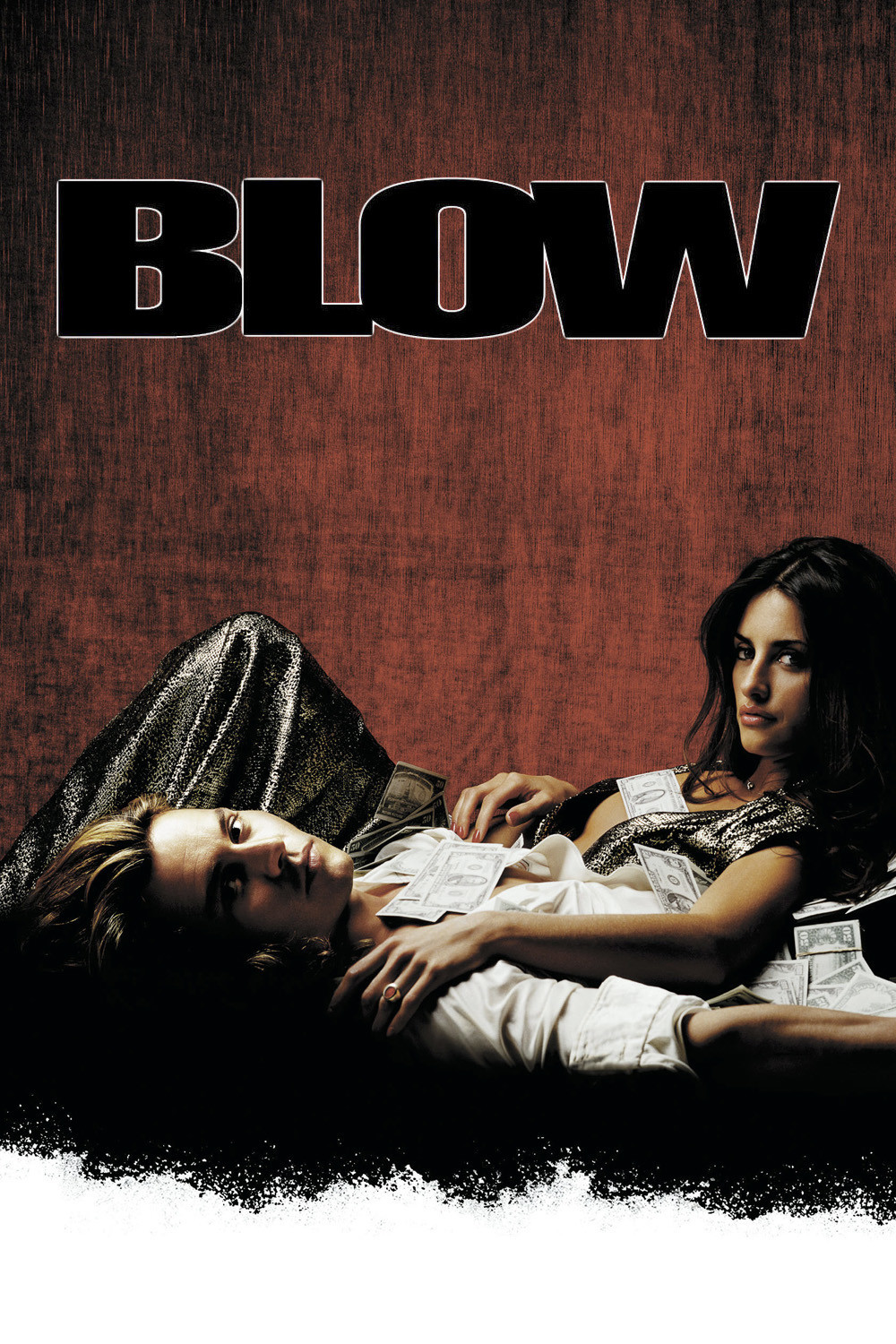

In Danbury Prison, he tells us, “I went in with a bachelor’s of marijuana and came out with a doctorate in cocaine.” As the 1970s roll on, the innocence of pot has been replaced by the urgency of cocaine. Soon George is making real money as a key distributor for his new friend Pablo Escobar (Cliff Curtis) and the Medellin drug cartel of Colombia. It’s with their cocaine that he racks up his record market share. And there is a new woman, Mirtha (Penelope Cruz), sexy as hell, but a real piece of work in the deportment department. At one point she gets him arrested by throwing a tantrum in their car.

The Colombians of course are heavy hitters, and George tries to protect his position by concealing the identity of his key California middleman, a onetime hairdresser named Derek Foreal (Paul Reubens). But the Colombians want to know that name really bad, and meanwhile George might be asking, is a rich man under the shadow of sudden death measurably happier than a man with a more mundane but serene existence? This is not, alas, a question that occurs to George Jung. Indeed, not many questions occur to him that are not directly related to getting, spending and sleeping with. The later chapters of his life grow increasingly depressing. He was never an interesting person, never had thoughts worth sharing or words worth remembering, but at least he represented a colorful type in his early years: the kid who smokes a little weed, finds a source, starts to sell and finds himself with a brand new pair of roller skates. By his middle years, George is essentially just the guy the Colombians want to replace and the feds want to arrest. No fun.

The dreary story of his final defeats is a record of back-stabbing and broken trusts, and although there is a certain poignancy in his final destiny, it is tempered by our knowledge that millions of lives had to be destroyed by addiction so that George and his onetime friends could arrive at their crossroads.

That’s the thing about George. He thinks it’s all about him. His life, his story, his success, his fortune, his lost fortune, his good luck, his bad luck. Actually, all he did was operate a toll gate between suppliers and addicts. You wonder, but you never find out, if the reality of those destroyed lives ever occurred to him.

The movie, directed by Ted Demme and written by David McKenna and Nick Cassavetes (from an as-told-to book by Bruce Porter), is well-made and well-acted. As a story of the rise and fall of this man, it serves. Johnny Depp is a versatile and reliable actor who almost always chooses interesting projects. The failure is George Jung’s. For all the glory of his success and the pathos of his failure, he never became a person interesting enough to make a movie about. The appearance of Ray Liotta here reminds us of Scorsese’s “GoodFellas,” which took a much less important criminal and made him an immeasurably more interesting character. And of course Al Pacino’s “Scarface” has so much style he makes George Jung look like a dry goods clerk. Which essentially he was. Take away the drugs, and this is the story of a boring life in wholesale.