I am a privileged person in many ways, but one of the ways in that I’m most privileged, I sometimes think, is that I got to lay eyes on Nat Hentoff’s office at the Village Voice back when the legendary paper had its offices off Union Square in Manhattan. This was in the early ‘80s, at a point when Hentoff had produced enough work and wielded enough influence (over thinkers, not politicians or real estate moguls) to have made several careers and spanned several lifetimes. In other words, the one time jazz critic, music impresario, and ever-tireless gadfly in defense of the First Amendment was as legendary at the paper where he wrote a column and kept an office. That office: I’d never seen anything like it before, and I’ve never seen anything like it since. From floor to ceiling it held what can only be called pillars, stacked, if you can call it that, side by side by side by side, of newspapers and books. You couldn’t see the light fixture at the top of the room. The only open space in the office was its small doorway, a few steps past which was a small desk with a typewriter and a lamp on it, and a chair in front of it.

It was unbelievable, not just because it was a fire hazard, not just because it was the sort of scene that inspired a weird “how do you find anything?” awe. It was also a testament to Hentoff’s attitude to the printed word. He hoarded it. Crazy love, you can call it.

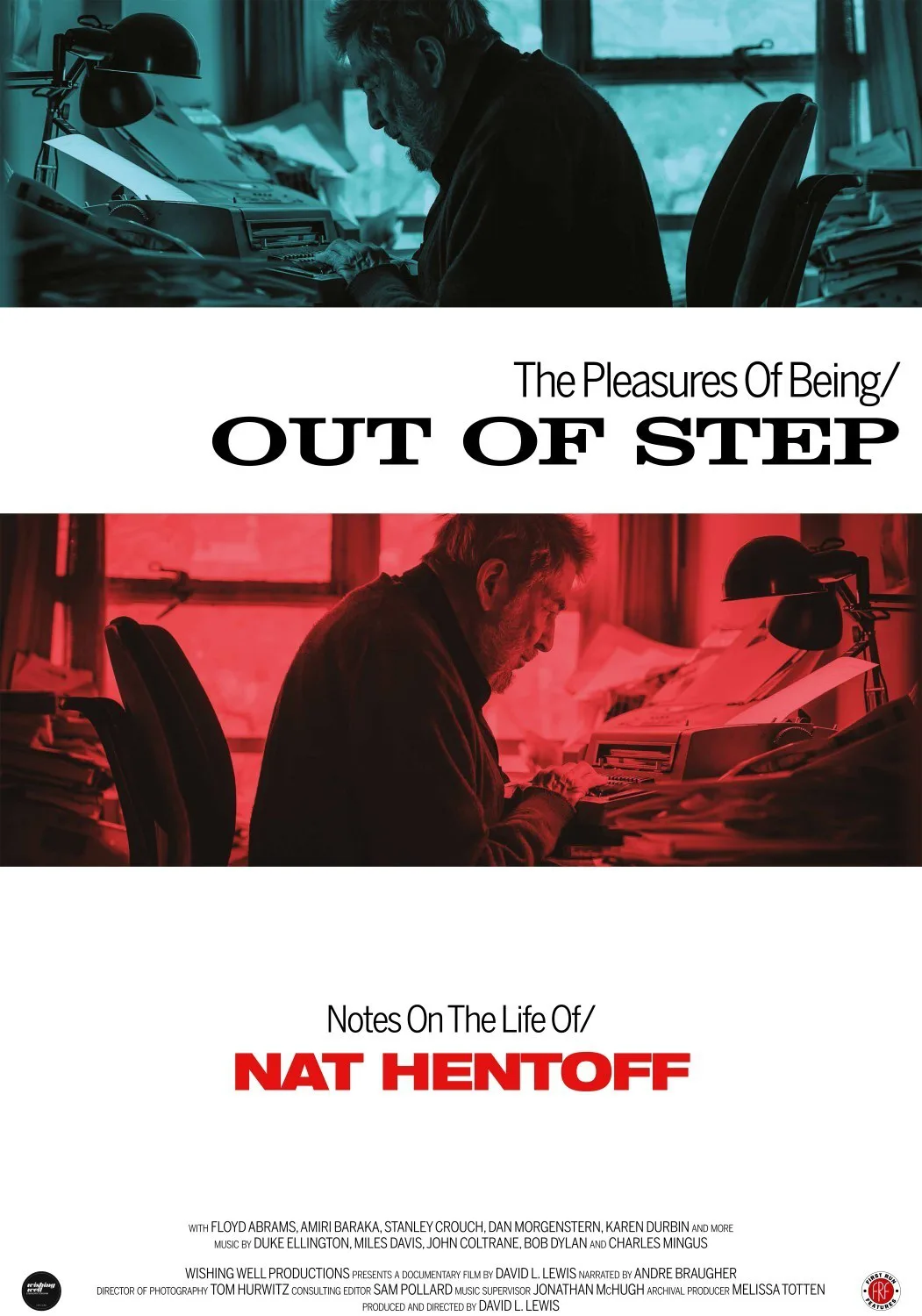

Sometimes, during David Lewis’ engaging documentary about Hentoff, “The Pleasures of Being Out Of Step,” when you look behind the now nearly 90-year-old Hentoff as he speaks from his home office—he was laid off from the Voice in 2006, putting arguably the final nail in the coffin of what that publication had once been, and stood for—you can see a version of that mess in miniature, a stray stack or two. But I wish the doc had a picture of that office, man. It would qualify for some kind of special effects Oscar, I promise.

Lewis subtitles his movie “Notes on the Life of Nat Hentoff,” and that’s wise; at less than 90 minutes in length, there’s only so much ground it can cover. The documentary takes a thematic rather than linear chronological approach. Lewis weaves together material on Hentoff’s love of jazz and his shoe-leather training as a wordsmith, and tries to make a case that the freedom that’s inherent in jazz as a musical form has something to say about the Constitution-guaranteed freedoms Hentoff has spent a good portion of his life articulating and defending. This First Amendment absolutist, an atheist and a Jew, achieved what some might consider a perverse notoriety when he defended the right of the American Nazi Party to stage a parade in Skokie, Illinois. Years later, Hentoff, whom many of his readers had taken for granted was a supporter of all liberal or liberal-related issues, made a lot of enemies by coming out with a stern position against abortion.

One might not think that bouncing back and forth between Jazz Hentoff and First Amendment Hentoff would make for consistently engaging viewing, but the movie is in fact remarkably fluid and never less than compelling. Like many biographical documentaries, it features an array of talking heads, but I can’t think of any such pictures featuring such an eclectic array of such figures: poet and rhetorical firebrand Amiri Baraka, constitutional lawyer Floyd Abrams, jazz giant Phil Woods, pioneering feminist journalist Karen Durbin, and many more, including Hentoff’s second wife Margot, who seems in many ways as formidable a figure as her spouse. (Full disclosure: while I’ve never had the pleasure of meeting Hentoff, Karen Durbin is a friend, as is another interviewee here, former record executive Regina Joskow.) The movie is also enlivened by a lot of fantastic archival footage, and again here the range is remarkable. Not many films boost cameos from both William F. Buckley and Thelonious Monk.

Despite his rep as “Always itching for a fight,” Hentoff here comes off as pretty mild mannered, and indeed his equanimity in speaking is cited by more than one interviewee as almost maddening. He articulates his point of view with great calm, reflecting on his “betrayals” of liberalism as nothing more than facets in a lifetime of argument. An argument in which he believes he holds the correct opinion, of course, but an argument nonetheless. Past accusations of homophobia and anti-feminism roll off of him like water off a duck’s back, but, as a viewer, I was disappointed that he didn’t address them more directly, and also that Hentoff doesn’t reflect at all on the sundered friendships so many arguments have left in their wake. “Don’t get yourself caught up in categories,” Hentoff recalls being told by Duke Ellington. Hentoff followed this advice while sticking like a barnacle to some very key principles. Even if you disagree with him, the man who emerges in this portrait is both an invaluable advocate of the arts and a moral hero. And he also wrote the liner notes to “Sketches of Spain.”