Some heroin users are not only addicted to the drug, but psychologically addicted to the needle; their dependency is inseparable from the ritual surrounding it.

Movies about drug addiction are also, sometimes, hung up on the fetishes and compulsions surrounding drugs. If we get a closeup of one needle penetrating the flesh in “The Panic in Needle Park,” we get half a dozen. This is too many; the physical reality interrupts our identification with fictional characters. The first actor in “Panic” to stick the needle in, in closeup, is Warren Finnerty, who was doing the same scene 10 years earlier in Shirley Clarke’s “The Connection.”

In the footsteps of that breakthrough film, Andy Warhol and various above-and underground followers favored the needle closeup as a handy, if artificial, way to shock an audience into the illusion that it is experiencing something other than shock. In “Trash,” Joe Dellesandro took so long to get the needle into his arm that you wondered if his veins were indeed as dense as his character’s incomprehension.

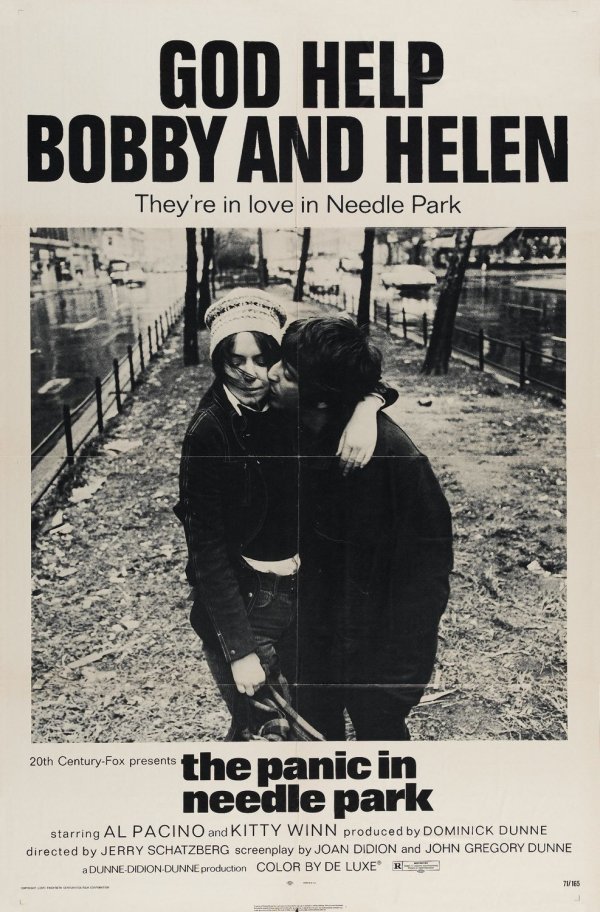

I mention this because in the original release 20th Century-Fox decided to play up the sensational elements in “The Panic in Needle Park,” and to overlook the qualities that make this a special and sometimes extraordinary movie. The New York Times carried one of those public confession ads that apologize for the ads that have gone before. “Did our ads blow it for ‘The Panic in Needle Park’!” the studio says. Their mistake (according to the current ad) was to play up the drama and love story in the movie, and play down the shock, the horror, the strong stuff. “If you see it,” the ad now promises, “it will sear your senses forever. And that’s the truth.”

Well, not quite. The shocking documentary details are there, and sometimes they work but usually they break a tone instead of creating one. That’s because (if you’ll permit me, 20th Century-Fox) this film is indeed a love story, and more specifically a carefully observed portrait of two human beings. If you go to see needles and blood and depravity, you may well be disappointed; the movie is more intelligent than your expectations.

That may be because of Joan Didion’s contribution; she wrote the screenplay with her husband, John Gregory Dunne, but somehow I think the character of the girl, Helen, came out of Didion’s private resources. Helen is a student from Indiana who falls in with a group of young addicts who live in, around and even under the corner of 72nd and Broadway. She is a girl both vulnerable and very tough, innocent and cynical, filled with two drives that shouldn’t ever conflict, but sometimes do: love and self-preservation.

Although Helen is an entirely original creation in a different kind of world, these qualities sometimes make her resemble the heroine of Didion’s Play It Like It Lays, a novel that makes the women in most novels seem as complex as telephone operators on billboards. Helen falls in love with Bobby (Al Pacino, in his first major role), a street-wise kid who was busted the first time when he was nine and who has been hustling drugs, stolen groceries, wayward TV sets and whatnot for a long time.

The quality I found fascinating about the movie was the relationship between Bobby and Helen, particularly since no long and strenuous effort is made to explain why Helen falls for Bobby. Helen is played by Kitty Winn, who won the best actress award at Cannes, and whose eyes tell us everything we need to know about her feeling for Bobby. She admires his cockiness, his outlaw spirit, his differentness from Fort Wayne, Ind.

There are a few scenes that are unforgivable. Bobby and Helen take the ferry out to the country and buy a puppy, which (wouldn’t you know) jumps overboard and drowns while Bobby and Helen are getting a fix in the ship’s john. This whole sequence, especially including the most annoying bird chirps since “Elvira Madigan,” should have been removed with all decent haste. There is also the question of how Bobby and Helen continue to somehow get good stuff — no bad stuff — during a citywide shortage of the stuff. And there are some other minor problems.

But the movie lives and moves. It is not filled with quick cutting or gimmicky editing, but Jerry Schatzberg’s direction is so confident that we cover the ground effortlessly. We meet the characters, we get to know the world. Especially, we get to know this relationship between Bobby and Helen, and thank God the filmmakers were tasteful enough not to kill them off at the end just because that’s so fashionable these days.