There’s a place roughly 90 minutes into Jesse Moss’ “The Overnighters” where, if the film had ended there, it would have been one of the year’s great documentaries. But in its last 10 minutes, something very surprising and unexpected happens, and what had been great becomes truly extraordinary.

This review will not describe that climactic episode, but only note that it’s at once very different from, yet strangely in keeping with, what has come before. In one sense, “The Overnighters” offers a fascinating and moving exploration of a perennial national theme, which has been an even greater concern since the beginning of the Great Recession: work. Yet, because this is America, that subject has a strange way of getting intertwined with another characteristic obsession: sex.

The documentary’s setting, Williston, North Dakota, is a typical American small town that has become very atypical due to the oil boom that brings hopeful would-be workers streaming in from all over the country. There is money to be made here, to be sure, but many of those arriving are on the edge of desperation, can’t find work immediately (or at all) and have nowhere to sleep. That’s what prompts Pastor Jay Reinke to persuade the congregation of the Concordia Lutheran Church to open their parking lot and parish house to many unfortunates who need shelter.

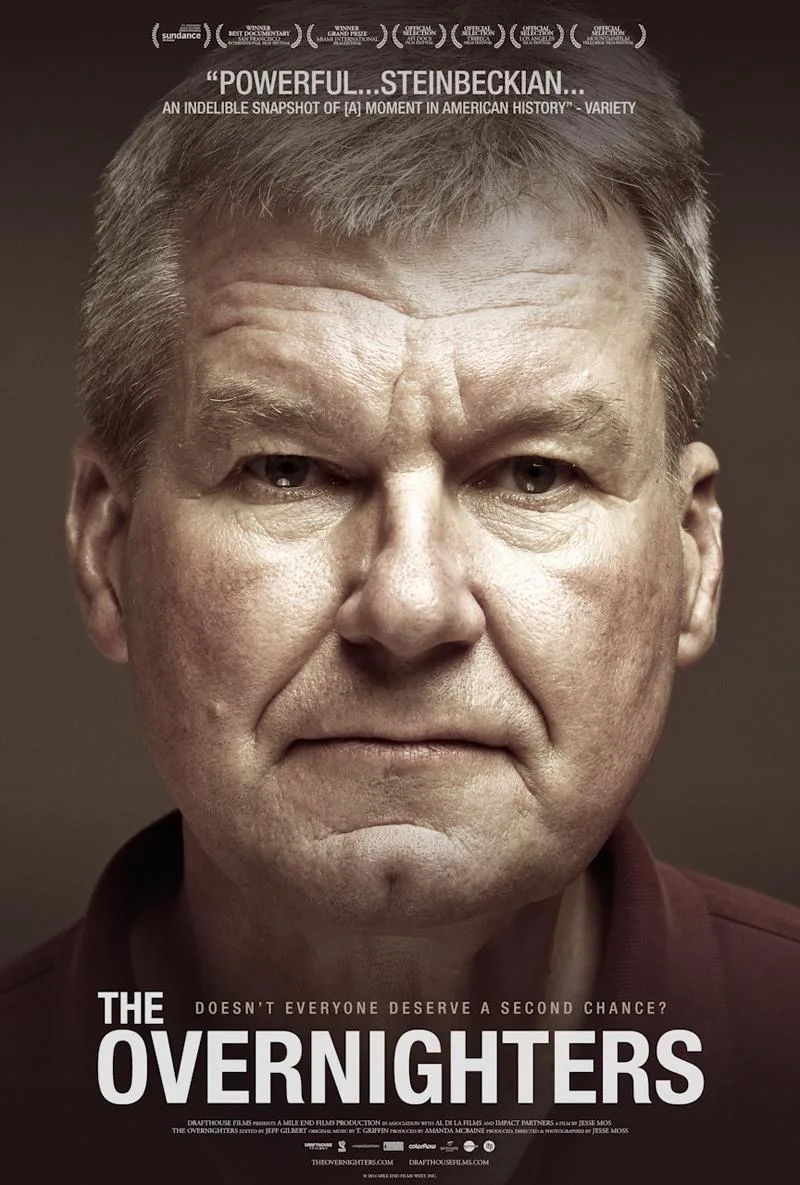

These “overnighters” sleep in the hallways and their cars. The passionate, ever-buoyant Reinke rouses them in the morning with hymns and tries to tend to as many of their needs as he can, especially in steering them toward work that will allow them to pay for lodging (the costs of housing have gone sky-high due to the oil boom). His work is a striking example of a man trying to live by the ideals of Christian charity, and many in his congregation seem to appreciate that, but the Overnighters program also strains their hospitality.

While following Reinke’s work in the church, the film also provides affecting, insightful portraits of some of the men who come to Williston hoping to improve their lot. Their need and desire for work is almost palpable. Some seem to have seen lots of tough times, yet there’s one fresh-faced 18-year-old named Keegan who’s just starting out and is lucky enough to score a good job that allows him to bring his girlfriend and baby son out. But even that doesn’t solve everything. His girlfriend doesn’t like being cooped up in a small apartment, so she goes back to Wisconsin, where Keegan’s father complains that their small town offers no opportunities to any young person.

That sense of an America where hard times have come to roost is ever-present in “The Overnighters,” and it reveals the dark flipside to the news reports of boom times on the plains of North Dakota. And, of course, the migration this boom occasioned is nothing new: in a sense, the tale the film tells is the same that brought generations of immigrants through Ellis Island and across the continent during the Gold Rush and Great Depression.

All of those earlier episodes upset established communities while causing the creation of ad hoc new ones, and that’s what happens here. The people of Williston and the members of Reinke’s congregation generally seem to want to do the right thing, but the influx of strangers disrupts a once comfortable way of life, and soon there are efforts to roll back or reverse the kind of hospitality Reinke advocates.

Likewise, there are tensions within the ad hoc community at the church. Though Reinke seems to be the most sincere and dedicated of pastors, his intensity–and perhaps something beneath it–rub some the wrong way. In particular, there are two men who become close to him–one serves as his deputy, the other lives briefly at his house–and end up seeing him as an enemy and denouncing him bitterly.

One small flaw in the film is that not enough is shown of these men’s previous interactions with Reinke for us to understand the reasons for their antipathy. Yet the consequences are severe: One man tells the local paper that some of the Overnighters are registered sex offenders, and Reinke allowed one to stay at his house, even though he has three teenage daughters and a son. (The offender in question, it should be noted, reportedly earned his status by sleeping with his 16-year-old girlfriend when he was 18, and Reinke had the support of his remarkable wife and kids in this decision as in his work with the Overnighters generally.)

In one striking scene, a newspaper reporter chases Reinke down a street bombarding him with questions about the sex offenders, and the running, upset pastor can’t bring himself to say anything. Later, though, he says this could be the end of his ministry. It’s not, but the specter of sexual predation is one factor that undermines the foundation of the Overnighters program. This scene also foreshadows the film’s amazing ending.

While “The Overnighters” has the feel of an epic, given what an expansive slice of America’s current economic experience it ponders, it’s also a very intimate one. Moss stayed with the Overnighters himself (partly because he couldn’t afford Williston’s inflated hotel prices) and was granted an extraordinary degree of access to the Reinke family. This makes for a film as rich emotionally as it is enlightening regarding the challenges facing people struggling to make a living.