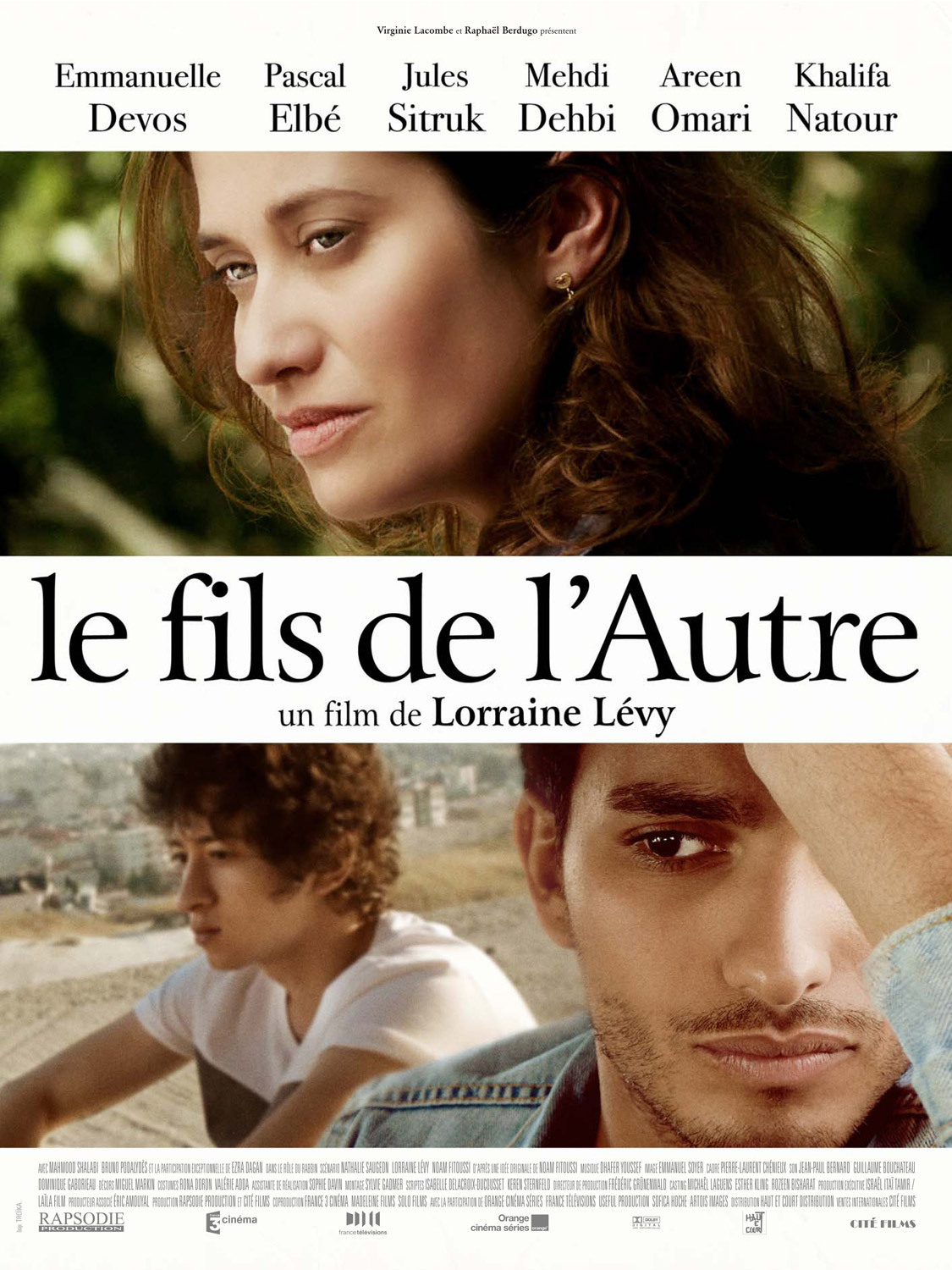

Two babies are born at about the same time in an Israeli hospital. One is Israeli. The other is Palestinian. They’re evacuated during a missile attack, accidentally switched and raised by each other’s families for the next 18 years.

That’s the plot line. When the mistake is discovered, how do the families react? What disturbs them more: that their son has been raised as an enemy or that he has been raised in another religion? That’s where “The Other Son” gets complicated.

The two fathers and the Palestinian’s brother are primarily concerned that their birth son has been raised by the “other side.” The mothers are more concerned about the return of the son they gave birth to. The way this difference plays out is all the more fascinating because the families on both sides are decent people.

Joseph (Jules Sitruk), the Palestinian by birth, has been raised by Orith and Alon Silberg (Emmanuelle Devos and Pascal Elbe). After he enlists in the Israeli Air Force, he takes a blood test that reveals the startling news that he cannot be the son of his parents. The way this information is carefully disclosed by a hospital spokesman speaks volumes: This is a rare nation in which your DNA determines your eligibility to serve in the military, and it’s clear the hospital has a lot of explaining to do.

Yacine (Medhi Dehbi), the Israeli by birth, has been raised on the West Bank by Leila and Said Al Bezaaz (Areen Omari and Khalifa Natour). His family is far from wealthy, but he had the good fortune to be educated in Paris.

The film’s co-writer and director, Lorraine Levy, is French, which helps explain this detail and several others: that Orith Silberg was born in France, and she and all the other characters, except for Said and Yacine’s brother Bilal (Mahmood Shalabi), speak French. In a sense that helps bridge the gap.

A key to Joseph’s character is that, although his father is in the Israeli military, and he himself intends to enlist, his actual dream is to become a singer-songwriter. It’s also important that Yacine, after some years in France, sees his plans for the future are in Europe. Neither boy is obsessed by his racial and religious identity.

This is definitively not the case with Bilal, and one of the shocking early moments occurs when he turns on his brother of 18 years and rejects him as an enemy. This emotional jolt may have as much to do with long-smoldering jealousy about Yacine’s Paris years than with his new identity; you see how tangled such things can become.

Orith invites Yacine to pay a visit. Then one day Joseph crosses to the West Bank and pays a call to Yacine. (The ease with which he can pass the Israeli border guards is ironic, since he is a born Palestinian.) Yacine’s family is caught off-guard; Yacine not as much. They do what any Arab or Israeli family would do, which is to offer their visitor food and drink, and the resulting meal is a study in social awkwardness and buried emotions, particularly on the part of the father and brother. In a moment of inspiration, Joseph begins to sing a song, and it’s a wonder how that melts through the frigid atmosphere.

The new reality starts to sink in. It probably helps that the two young men are now well-launched along their adult paths; I wonder how this story would play out if they were both still quite young.

What difference did the switch make, really? In superficial ways, the two boys aren’t so different: they both “look” Jewish or Arab, take your choice. How do they now feel about themselves? Joseph quizzes his rabbi: “Am I still Jewish?” The rabbi tells him he was one of his best students, but his mother was not Jewish, and so, no, he isn’t, but he can convert. What about Yacine? Is he now Jewish? Technically, yes.

In an altered situation, it is easy to imagine Joseph and Yacine fighting and even killing each other, each one mistaken by the other for the enemy. The significance of this parable is there to be seen.