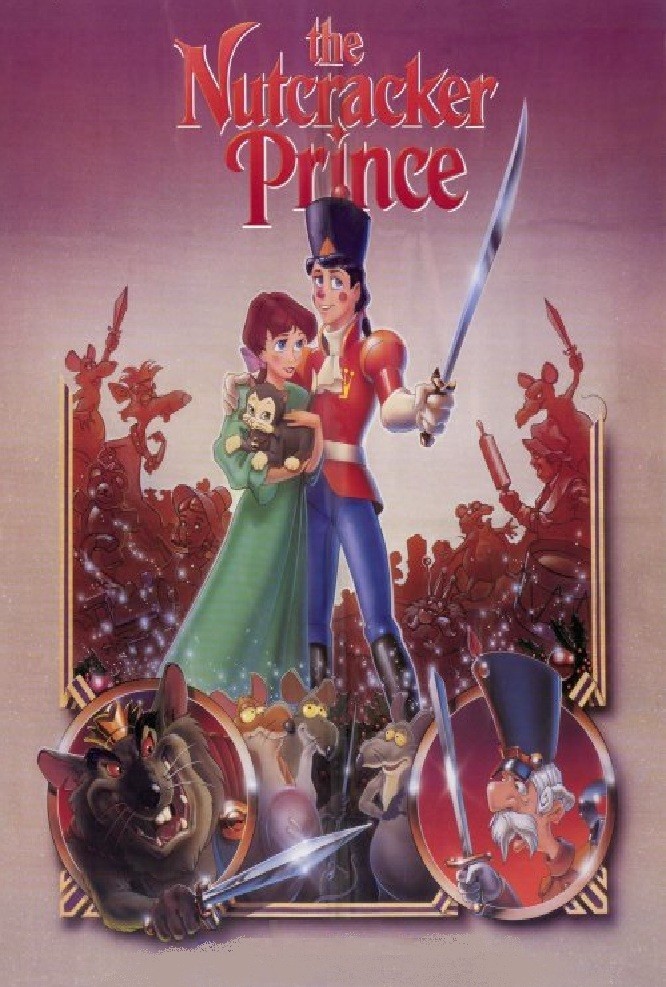

Where did it start, this idea in our society that death was a solution? Wasn’t there a time when children’s stories were more innocent and ended with victory and defeat, vindication and success, rather than with a fight to the finish? How did we get hung up on the notion that the only way out of a situation is to fight, and the only way to win is by killing? I ask these questions on the occasion of seeing a children’s animated film named “The Nutcracker Prince,” which some parents may want to take their children to because of its identification with the music by Tchaikovsky. This is not an evil film; it is mediocre, but innocuous.

But its climax is a battle to the death. (Children’s toys miraculously come to life, there is a confrontation, and a character falls lifeless from the top of a giant Christmas tree.) Why was this necessary? And why are fight scenes and violent deaths now so routine in children’s films and on TV? In real life, a person who believes he cannot win without the death of his opponent is seen as a monster.

But in the fables we feed to children, the plots are often just that simple: The problem is that the villain is alive, and the solution is to kill him.

What about other kinds of solutions, in which the villain is brought to see the light? Or the characters learn that if they listen to one another, they can work out their differences? Or in which the plot is not about a bad guy at all, but about some kind of problem that the characters are trying to solve? Where did this violent undercurrent come from in our society? Does it come from the modern sports culture, where winning is the only thing? From adult TV shows, which use violence as a cheap substitute for thought? Children’s stories used to live in a gentler, more fanciful universe. No more.

And so we get movies like “The Nutcracker Prince,” an animated feature that is not particularly inspired – nothing in the animation or the story shows anything but the most conventional minds at work – and the big moment is the death of a bad character. Parents taking their children in the hope of exposing them to something resembling culture will, indeed, hear snatches of Tchaikovsky’s “Nutcracker Suite,” cheerfully cut up into ribbons and stuck in here and there.

But the level of imagination in the story is about as inventive as on most Saturday morning cartoon shows.

There is no great tragedy here. Just another sad little shred of evidence about the times we live in.

In the real world, when a person is so lacking in empathy that he kills someone else simply for his own convenience, he is known as a psychopath. Why does our society give its children so many stories in which the heroes, not the villains, are psychopaths?