The tone of life in Rio de Janeiro is established in an early scene in Walter Salles‘ “Central Station,” as a train pulls alongside the platform and passengers crawl through the windows to grab seats ahead of the people who enter through the doors. In this dog-eat-dog world, Dora (Fernanda Montenegro) has a little stand in the rail station where she writes letters for people who are illiterate.

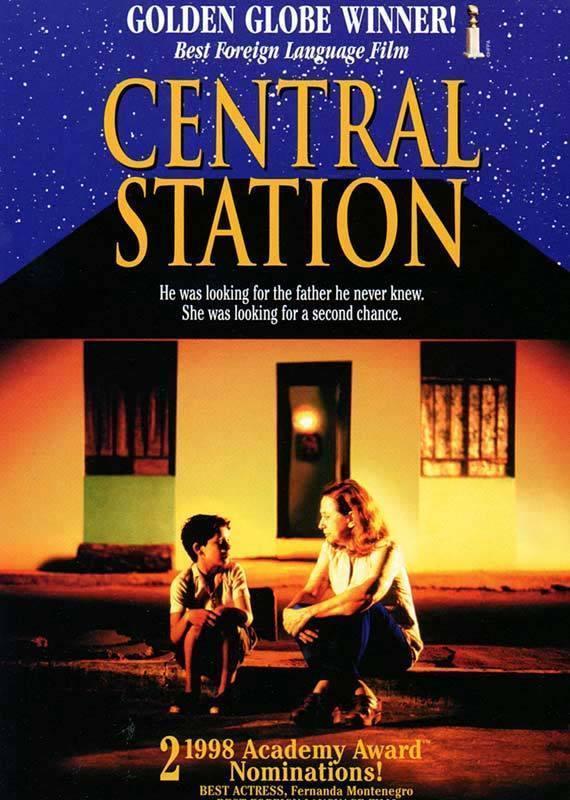

A cynic, she destroys most of the letters. One day a mother and son use her services to dictate a letter to the woman’s missing husband. Soon after, the mother is struck and killed by a bus. The kid knows one person in Rio: Dora. He approaches her for help, and her response is brief: “Scram!” The key to the power of “Central Station” is in the way that word echoes down through most of the film. This is not a heartwarming movie about a woman trying to help a pathetic orphan, but a hard-edged film about a woman who thinks only of her own needs. After various attempts to rid herself of young Josue (Vincius de Oliveira), she finally sells him to an adoption agency and uses the money to buy herself a new TV set.

There’s not a shred of doubt or remorse as she settles down before the new set. But the whole story is known by her friend Irene (Marilia Pera, who played the prostitute who adopts the street kid in “Pixote“). “Those children aren’t adopted!” she cries. “They’re killed, and their organs are sold!” As if it is a great deal of bother, Dora then steals Josue back from the “orphanage,” and finds herself, against her will and beyond her comprehension, trying to help him find his father, who lives far away in an interior city.

“Central Station” then settles into the pleasures of a road movie, in which we see modern Brazil through the eyes of the characters: the long-haul trucks that are the lifeline of commerce, the sprawling new housing developments, the hybrid religious ceremonies, the blend of old ways and the 20th century. Whether they find the father is not really the point; the film is about their journey and relationship.

The movie’s success rests largely on the shoulders of Fernanda Montenegro, an actress who successfully defeats any temptation to allow sentimentality to wreck her relationship with the child. She understands that the film is not really about the boy’s search for his father, but about her own reawakening. This process is measured out so carefully that we don’t even notice the point at which she crosses over into a gentler person.

The boy, 10-year-old Vincius de Oliveira, was discovered by the director in an airport, shining shoes. He asked Walter Salles for the price of a sandwich, and Salles, who had been trying for months to cast this role, looked at him thoughtfully and saw young Josue. Whether he is an actor or not I cannot say. He plays Josue so well, the performance is transparent. I hope he avoids the fate of Fernando Ramos da Silva, the young orphan who was picked off the streets to star in “Pixote,” later returned to them and was murdered. I met de Oliveira at the Toronto Film Festival, where, barbered and in a new suit, he looked like a Rotarian’s nephew.

It’s strange about a movie like this. The structure intends us to be moved by the conclusion, but the conclusion is in many (not all) ways easy to anticipate. What moved me was the process, the journey, the change in the woman, the subtlety of sequences like the one where she falls for a truck driver who doesn’t fall for her. It’s in such moments that the film has its magic. The ending can take care of itself.