Following up his Oscar-nominated debut film “Lunana: A Yak in the Classroom,” Bhutanese filmmaker Pawo Choyning Dorji’s “The Monk and the Gun” is a droll political satire set in the year 2006 as the Kingdom of Bhutan transitions towards becoming the world’s youngest democracy. Lusciously lensed by cinematographer Jigme Tenzing, the ensemble comedy examines how the country’s upcoming mock elections affect the titular monk, a rural family, an election official, and a desperate liason from the city, all of whose lives collide in minor and major ways.

After hearing about the upcoming mock elections on the radio, the elderly lama (Kelsang Choejey) of the rural village of Ura requests that his attendant Tashi (a wonderfully wry Tandin Wangchuck) bring him two guns before the full moon—also the day of the elections—to “set it right.” What exactly he means by this ominous and vague statement is left unanswered until the film’s charming denouement.

As Tashi makes his way on foot in search of guns, election official Tshering (Pema Zangmo Sherpa) arrives, observing as the rural population is taught how to vote. Fictional parties are set up: Blue representing freedom and equality, red representing industrial development, and yellow representing preservation. Although the villagers are told to vote for the party they think will “bring them the most happiness,”— democracy, Tshering insists is paramount for the country’s Gross National Happiness—they are also instructed how to hold a rally. Villagers are arbitrarily split up and told to yell at each other. A lesson that presses an elderly villager to ask Tshering why they are being taught to be rude, “This isn’t who we are,” the old woman admonishes.

Indeed, much of the film criticizes the ways in which political parties can polarize families. Tshering is aided by a local woman named Tshomo (Deki Lhamo) whose family is being torn apart by the impending election. A bitterness has come between her husband Choephel (Choeying Jatsho) and her mother, who support opposing parties, leading them to no longer speak. When their daughter Yuphel (Yuphel Lhendup Selden, who gives a wonderfully naturalistic performance in her film debut) asks her father for an eraser she needs for school, he tells her he’s focusing on the election, now, so she can be Prime Minister in the future. “I don’t want to be Prime Minister, I just want my eraser,” she retorts. Choephel is so wrapped up in the upward mobility being aligned with a politician can bring in later—everything from sending his daughter to a city school to getting a bigger television—that he neglects his family’s immediate needs.

Dorji’s film is also critical of the role media, like television, plays in shaping Bhutan’s future. In 2006 it had been less than a decade since the country had lifted a ban on both television and the internet, allowing a two-way connection between their traditional way of life and the world at large. The upcoming mock elections are being covered by international outlets like CNN, BBC, and Al-Jazeera, putting pressure on officials like Tshering, who often seem more concerned about how the world will perceive this fledgling democracy than what the people actually want.

The only television programs any civilian seems to watch are either election ads or American pop culture. In one of the film’s funniest moments, Tashi arrives at a remote shop for a refreshment (opting for “black water” aka Coca Cola) before settling in with a group crowded around its television. Footage of the moon landing overscored by Neil Armstrong’s famous words “one small step for mankind” slowly reveals itself to be the logo for MTV, where a commercial for the Daniel Craig starring James Bond film “Quantum of Solace” plays. The omnipresence of 007 and his penchant for weapons like AK-47s becomes a running motif, specifically of America’s unchecked gun culture.

Tashi eventually locates an antique rifle owned by a remote farmer. The rifle traces back to the American Civil War, before it found its way to Bhutan where it allegedly killed many Tibetans. Unbeknownst to Tashi, this rare relic is also being sought by a seedy American collector, Mr. Ron (Harry Einhorn), whose guide, the urban-dwelling Benji (Tandin Sonam), risks arrest in hopes of a big payday that will help out his ailing wife. Modern city life comes with its own trials and tribulations.

The American character’s full name is Ronald Coleman, a not so subtle homage to the actor Ronald Colman who starred in Frank Capra’s classic fantasy “Lost Horizon.” In that 1937 film, Colman played a diplomat whose plane crashes in the Himalayas, leading him to discover a treasured city unchanged by time, the mythical Shangri-La. Even after Bhutan’s transition to democracy, Western media headlines often still exoticize the country, referring to it as “the world’s last Shangri-La.”

Mr. Ron is of course a stand in for America. His obsession with guns, his impatience, his insistence that money can solve any issue and that everyone has a price, finds resistance with the rural Bhutanese farmer, whose constant befuddling actions are rooted in kindness rather than in profit, much to the American’s consternation. Later when an election official, excited to meet an American for the first time, is eager to talk about democracy with him, Mr. Ron brushes him off, unwilling and more than likely unequipped to truly engage in a meaningful discussion on the subject.

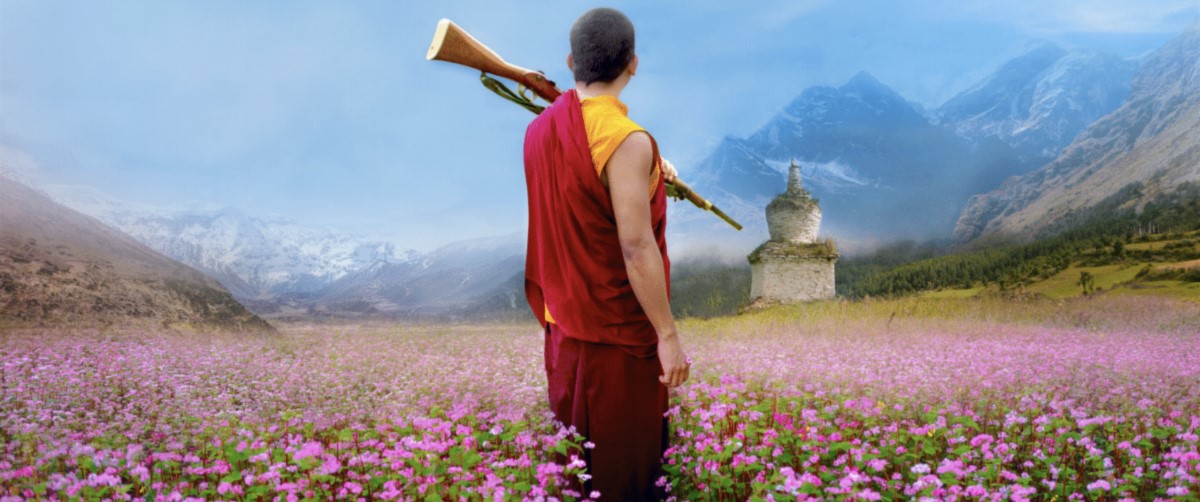

Dorji weaves these storylines together in an Altman-esque manner. Characters come in and out of each other’s lives seamlessly, sometimes without even realizing it. Like “Nashville,” not all of the characters are given equal screen time, yet each is imperative for the tapestry of life Dorji wishes to present. The Bhutanese countryside itself is also a character, with many scenes filmed in wide shots, centering Tashi and others within a bucolic tableau of flowers and animals held harmoniously all together in Dorji’s frame.

When the storylines eventually converge, this moment takes place at the village’s stupa, which the lama says represents the enlightened mind of the Buddha. Located in the middle of a field between the mountains and the village, the stupa is a sacred and ceremonial place, a place of transition. It is where travelers like Tashi come to center themselves, either after a long journey or at its completion. The people of Bhutan, too, must find their center during this transitional phase. Change is inevitable, as is the country’s journey towards modernization. The most important thing is how the Bhutanese take on these changes in a way that still reflects who they are as a people.

For many people around the world, a thing’s worth is measured in the price people are willing to pay for it, like the money Mr. Ron offers for the gun, or the lives people have lost in countries where democracy had to be fought for and hard won. In a place whose greatest aim is its population’s happiness, Dorji’s “The Monk and the Gun” contemplates whether complete modernization of his country is worth the price of this very happiness.