The opening shots of “The Mask” look like they were salvaged from a desperately low-budget 1950s science fiction movie. Marine salvage operations lead to the rupture of ancient chest that has rested for ages on the bottom of the bay, and a curious wooden mask floats to the surface.

Not long after, disconsolate bank teller Stanley Ipkiss, a genial nerd played by Jim Carrey, is staring into the dark waters and contemplating suicide. He has just been bounced from a nightclub – the latest in a long series of humiliations. But he has a good heart, and when he sees the mask floating with some rubbish, he thinks it is a drowning victim and jumps in to save it.

All he brings to shore is the mask. But when, later that night . . .

Transformation scenes are of course the soul of comic book fiction. Billy Batson shouts “Shazam!”, Clark Kent darts into a phone booth, Bruce Wayne becomes Batman, and in every case an insignificant wimp becomes a superhero. No wonder adolescent boys respond to these stories so powerfully.

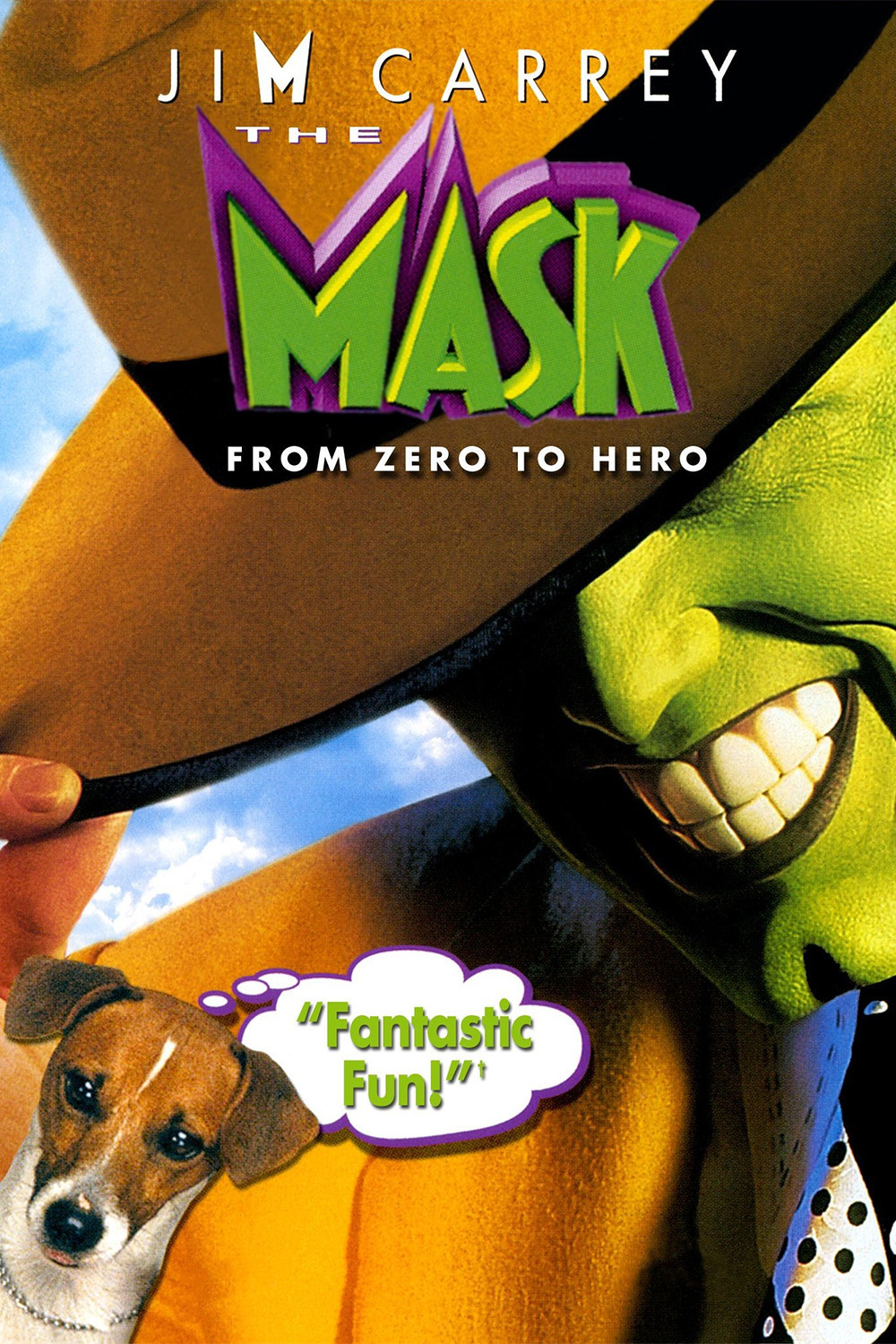

Consider what happens to Stanley when he puts on the mask. He is instantly transformed into a maniacal whirlwind of energy, dressed in a 1940s-style zoot suit – a cross between the Joker and Aladdin’s genie, with elements of the Shadow.

“The Mask” is a perfect vehicle for the talents of Jim Carrey, who underwhelmed me with “Ace Ventura: Pet Detective” but here seems to have found a story and character that work together with manic energy. One of the key design decisions on the movie must have involved the Mask character’s makeup. It transforms Carrey’s features into a much larger, comic-bookish parody, but at the same time the features are still able to move in a lifelike way. The notes with the film explain that makeup expert Greg Cannom realized Carrey’s exaggerated facial expressions are part of his essence, and didn’t want them lost behind makeup.

The result is a movie character who seems half real, half animated.

And the director, Charles Russell, is able to use special effects to move effortlessly between what might be possible and what is certainly not, as the Mask whirls like a beebop dervish and triumphantly prevails in situations that would have baffled poor Stanley Ipkiss.

The story begins with Stanley as a hapless bank clerk, who is hopelessly besotted by a beautiful customer, Tina Carlyle (Cameron Diaz). She flirts with him in the bank while taking secret videotape of the vault for her boss, the slimy Dorian Tyrel (Peter Greene), who runs the Coco Bongo Club, where, of course, Tina is the slinky chanteuse.

Cameron Diaz is a true discovery in the film, a genuine sex bomb with a gorgeous face, a wonderful smile, and a gift of comic timing. This is her first movie role, after a brief modeling career.

It will not be her last. Her chemistry with the Carrey character holds together a plot that is every bit as derivative as it can be, and when she dances with the Mask the result is one of those scenes when movie magic really works.

The story otherwise involves Richard Jeni as Charlie, Stanley’s best friend at the bank, who introduces him to the mysteries of the Coco Bongo Club; Peter Riegert as a cop who notices the Mask’s tie seems to be made of the same material as Stanley’s unspeakable pajamas; and Milo, Stanley’s dog, who is at least as clever as his master.

The art design on the movie goes for the lurid 1940s film noir look of a lot of superhero comic books, and the Coco Bongo Club looks recycled out of “Gilda” and a dozen other movies with elegant nightclubs. Stanley’s apartment resembles a teenage boy’s bedroom; all that’s missing is a sign on the outside of the door saying “Keep Out! This means you!” The look of the film is as much fun as anything else.

I was not one of the admirers of “Ace Ventura: Pet Detective.” Millions were, however. I thought the story surpassed stupidity, and not in interesting ways. But I could sense some of Carrey’s unrestrained energy and gift for comic invention, and here – where the story and the decor and the idea of the mask provide an anchor for his energy – Carrey demonstrates that he does have a genuine gift. It is said that one of the indispensable qualities of an actor is an ability to communicate the joy he takes in his performance. You could say “The Mask” was founded on that.