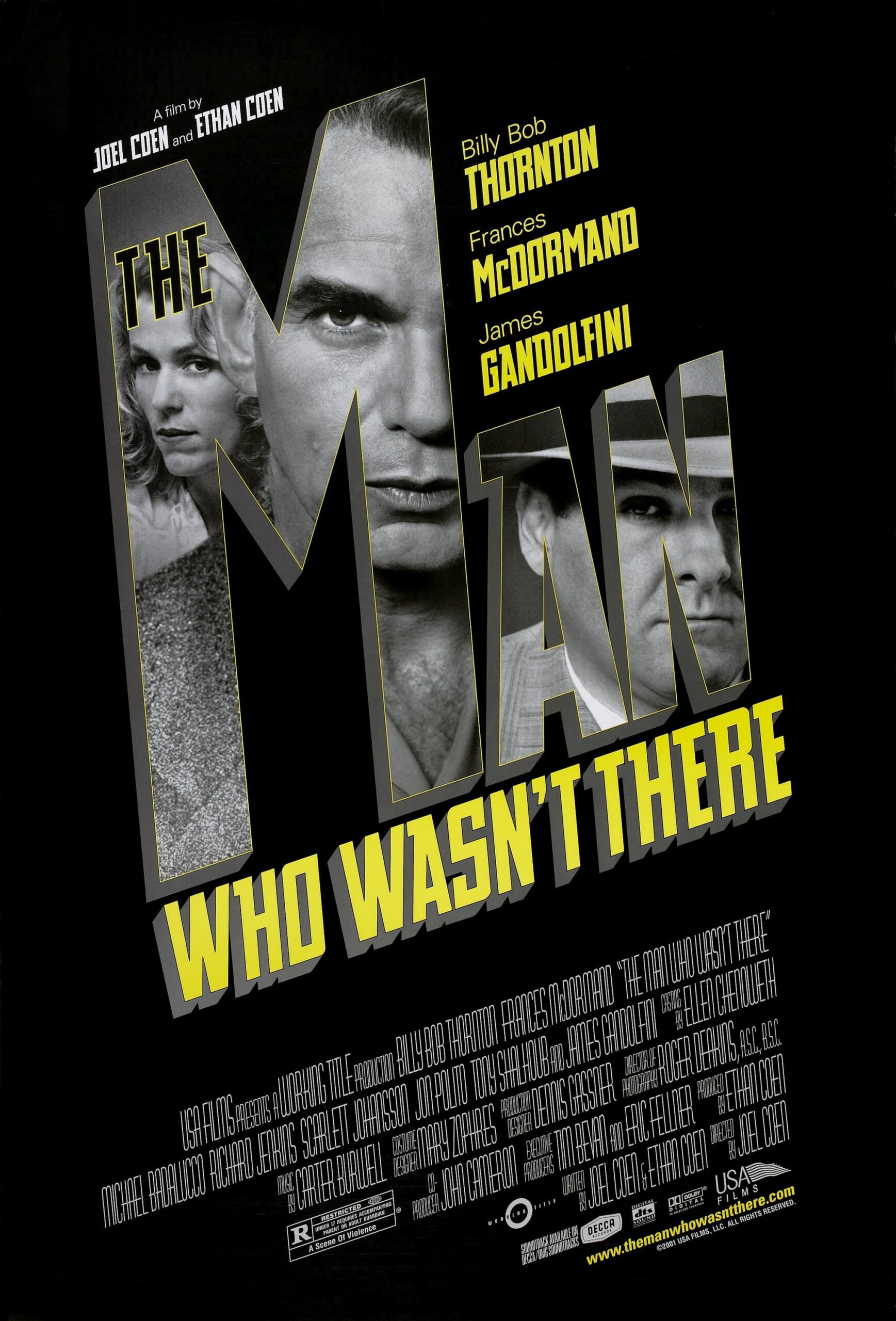

The Coen Brothers’ ”The Man Who Wasn’t There” is shot in black-and-white so elegantly, it reminds us of a 1940s station wagon — chrome, wood, leather and steel all burnished to a contented glow. Its star performance by Billy Bob Thornton is a study in sad-eyed, mournful chain-smoking, the portrait of a man so trapped by life he wants to scream.

The plot is one of those film noir twisters made of gin and adultery, where the right man is convicted of the wrong crime. The look, feel and ingenuity of this film are so lovingly modulated you wonder if anyone else could have done it better than the Coens.

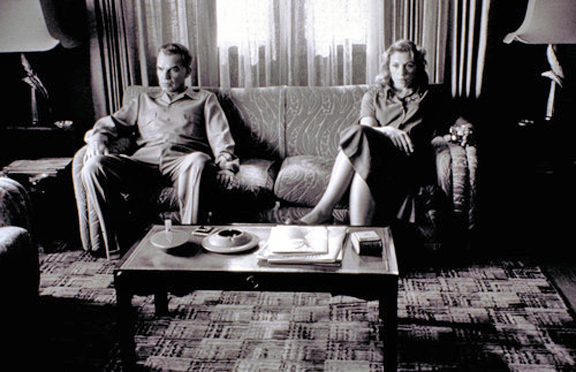

Probably not. And yet, and yet–for a movie about crime, it proceeds at such a leisurely pace. The first time I saw it, at Cannes, I emerged into the sunlight to find Michel Ciment, the influential French critic, who observed sadly, ”A 90-minute film that plays for two hours.” Now I have seen it again, and I admire its virtues so much I am about ready to forgive its flow. Yes, it has a deliberate step–but is that entirely a fault of the film, or is it forced by the personality of Ed Crane (Thornton), the small-town barber who narrates it? He is not a swift man, and we get the impression that the crucial decisions in his life–his job, his marriage–were made by default. He has the second chair in a two-barber shop, next to his talkative brother-in-law Frank (Michael Badalucco). He spends most of his waking hours cutting hair and smoking, the cigarette dangling from his lips as he leans over his clients. (This is exactly right; the movie remembers a time in America when everyone seemed to smoke all the time, and I cannot think of Darrel Martin, the barber on Main Street in Urbana, without remembering the smoke that coiled from his Camel into my eyes during every haircut.) Ed Crane has the expression of a man stunned speechless by something somebody else has just said. He is married to Doris (Frances McDormand), who is the bookkeeper down at Nirdlinger’s Department Store.

She works for Big Dave (James Gandolfini), and when Dave and his wife come over to dinner, Doris and Dave laugh at all the same things while Ed and Dave’s wife stare into thin air. Ed thinks his wife may be having an affair. He handles this situation, as he handles most social situations, by smoking.

The story then involves developments I will not reveal–double and triple reverses in which two people die in unanticipated ways, at unanticipated hands, and Doris ends up in jail. Ed mortgages the house to pay for the best lawyer in California, Freddy Riedenschneider (Tony Shalhoub), who is the defense attorney at two trials in the movie. Ed, who narrates the entire movie with deadpan objectivity, reports his summation for the jury: ”He told them to look not at the facts, but at the meaning of the facts. Then he said the facts had no meaning.” The Coens have always had a way with dialogue. I like the way Ed’s narration tells us everything we need to know about Ed while Ed seems to be sticking strictly to the facts. I like the way Freddy Riedenschneider tells Ed, ”I’m an attorney. You’re a barber. You don’t know anything.” And a conversation in Ed’s car between Ed and Birdy Abundas (Scarlett Johansson), a teenage pianist he has taken an interest in. ”You know what you are?” she asks him, after he insists she has talent. ”You’re an enthusiast!” Yes, and he is mostly enthusiastic not about Birdy’s music but about Birdy, but too fearful to make the slightest admission of his feelings. She lacks all such inhibition, and when she attempts to demonstrate her gratitude in an extremely direct way, all he can think of to say is, ”Heavens to Betsy!” Classic film noir specialized in bad luck and ironic turns of fate. A crime would be committed flawlessly, and then the perp would be trapped by an inconsequential, unrelated detail. That’s what happens here, but with the details moved laterally one position, so that you are obviously guilty–not of the crime you committed, but of the crime you didn’t commit.

Film noir is rarely about heroes, but about men of small stature, who are lured out of their timid routines by dreams of wealth or romance. Their sin is one of hubris: These little worms dare to dream of themselves as rich or happy. As the title hints, ”The Man Who Wasn’t There” pushes this one step further, into the realm of a man who scarcely exists apart from his transgressions. I kill, therefore I am. And he doesn’t even kill who, or how, or when the world thinks he does (although there is a certain justice when he receives his last shave).

Joel and Ethan Coen are above all stylists. The look and feel of their films is more important to them than the plots–which, in a way, is as it should be. Here Michel Ciment is right, and they have devised an efficient, 90-minute story and stretched it out with style. Style didn’t used to take extra time in Hollywood; it came with the territory.

But ”The Man Who Wasn’t There” is so assured and perceptive in its style, so loving, so intensely right, that if you can receive on that frequency, the film is like a voluptuous feast. Yes, it might easily have been shorter. But then it would not have been this film, or necessarily a better one. If the Coens have taken two hours to do what hardly anyone else could do at all, isn’t it churlish to ask why they didn’t take less time to do what everyone can do?